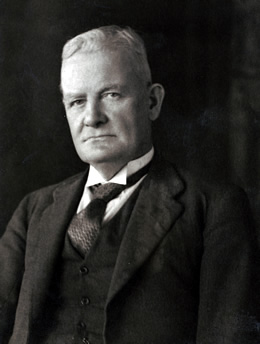

BARNES, John (1868–1938)

Senator for Victoria, 1913–20, 1923–35 (Australian Labor Party)

‘The story of John Barnes’, said Albert Monk, ACTU president in 1938, ‘is also the history of the Australian Labor movement’. Barnes was born on 17 July 1868 at Hamilton, near Kapunda, South Australia, son of John Thomas Barnes, a labourer from Somerset, England, and his wife Mary, née Cummeford, from County Clare, Ireland. He acquired the basic elements of a primary education and by the age of seventeen was wandering from state to state in search of work. As he ‘humped Matilda’ down the tracks of ‘the Vast Outback’, he found work as a rouseabout, shed hand and tar boy around the shearing sheds, and later as a blade shearer. At night, he unrolled his swag to read the works of Adam Smith, Henry George and Robert Blatchford.

Barnes moved to Broken Hill and in 1887 joined the Amalgamated Shearers’ Union (ASU). He worked as a miner and in 1894 was involved with the amalgamation of the ASU with the General Labourers’ Union to form the Australian Workers’ Union (AWU). In 1908 he was the AWU’s first political organiser in South Australia, and by 1909 was in Ballarat where he became secretary of the AWU’s Victoria–Riverina branch, holding the position until 1913. In 1919 he was chairman of the board of directors for the Ballarat Evening Echo, when, along with other representatives of various newspapers, he attended a meeting of the ALP Federal Executive; the group is described in Caucus minutes as the ‘Publicity Bureau’. He was a member of the Victorian executive of the Labor Party for sixteen years, serving as president in 1920.[1]

Barnes was elected to the Senate in May 1913 and re-elected following the 1914 simultaneous dissolution. He would continue to be a stalwart of the AWU, serving as AWU federal president from 1923 until his death in 1938. He seems seldom to have lost an opportunity to remind the Senate of the connection between the AWU and the Labor Party. ‘There are’, he said in 1918, ‘over 30,000, or a Division and a half of members of the Australian Workers Union fighting for Australia at the Front. They were politically in the ranks of Labour before they went to the Front, and when they return they will have to continue in the ranks of Labour’. Barnes’ principal interests lay in matters likely to affect the welfare, employment and working conditions of the Australian ‘industrialist’—the working man and woman. While he did not always agree with AWU policy, for instance over the Bruce–Page Government’s 1926 referendum proposals, which would have extended Commonwealth industrial authority, he was cautious in his response to controversial issues. He regularly recalled that the AWU had been ‘behind the agitation for a sensible means of settling industrial troubles’, and had advocated ‘arbitration in substitution for the strike’. A capable negotiator, in February 1929 he attended a meeting of the Federal Executive, as President of the AWU, in an attempt to restore harmony between the New South Wales branches of the ALP and the AWU.[2]

Barnes’ dry wit retained much of its bush beginnings. Debating conscription in 1916, he was asked what he would do if he heard that an enemy raiding party of 10 000 had landed at Port Darwin. His response was fairly typical: ‘Leave them there until a few Australian Workers Union men went up there shearing next year, and they would account for them’. He revelled in the bushman’s love of ‘leg-pulling’, and once convinced a visitor to the parliamentary dining room that an item on the menu was that of carpet snake, describing the dish as a ‘much-prized delicacy’ among AWU men in Queensland.

Barnes was a trenchant critic of the lack of coordination between Commonwealth and state governments on immigration policies. He opposed independent campaigns by state governments (especially in Victoria) to bring to Australia thousands of new British settlers. He declared that many of the new immigrants had been given misleading information. ‘Any man’, he said, ‘who takes a train into the country will see hundreds of men carrying their swags’. In 1926 he said: ‘It is ridiculous to talk of bringing unemployed from overseas to a country where there are already 50,000 unemployed’.

His passionate concern to ensure justice for the individual led to his taking up causes on behalf of ‘people of enemy origin’. He was affronted by the disenfranchisement of those of German birth who had sons fighting with the AIF. He objected strongly to the War Precautions Bill being used by the Hughes Government ‘for the most mean and despicable political purposes’. Equally strongly, he opposed any attempt to censor wartime reporting of parliamentary debates.

When the conscription issue split the Labor Party in 1916 Barnes, whose sympathies were with the centre of the party, was disillusioned: ‘I never thought that [W. M. Hughes] would turn his back on the principles of a lifetime’. Nevertheless, like most of his Labor colleagues, Barnes continued wholeheartedly to support the war effort, from March to August 1916 serving as a member of the Hughes Government’s Commonwealth Prices Adjustment Board. In a major speech in December 1916 he pointed out that loss of men to the war was affecting Australia’s industries and reminded senators that the current extent of Australia’s contribution far exceeded initial estimates. He strongly attacked what he saw as Hughes’ underhand efforts to influence the outcome of the troops’ vote during the conscription referendum.[3]

He was defeated at the 1919 federal election that saw the introduction of preferential voting, which led to the subsequent entry of members of the Country Party into the Parliament. Referring to the fact that only one Labor senator remained—Senator Gardiner—Barnes’ attitude was characteristic: ‘It is not my nature to remain silent, and so, when I vacate my seat in this august Chamber I shall take up my work outside. All my life I have been in the stress of the industrial and political world, and in future I shall do my share of the work as I have done in the past’. He was re-elected to the Senate in December 1922.

During debate on the Defence Equipment Bill of 1924 Barnes’ views reflected ALP opposition to the Government’s proposal to purchase two 10 000-ton cruisers from Britain for the Australian fleet. While arguing that if the ships must be built they should be built in Australia, Barnes revealed his interest in the creation of a modern system of air defence. He would remain an enthusiastic proponent of the superiority of air power and of Australia’s need to develop airships and aeroplanes ‘suitable for defence’. As a longstanding member of the Joint Standing Committee on Public Works he supported recommendations which included the erection of a wharf at Rabaul, New Guinea, an aircraft depot at Laverton in Victoria and a RAAF station at Richmond in New South Wales.

As the country drifted towards depression, Barnes could not accept that the economic situation was as bad as forecast. He continued to defend the right to strike, in spite of the fact that by 1925 maritime unions were generating protracted industrial disputes and were showing some contempt not only for the arbitration system but also for the ALP. By 1926, in spite of some Country Party opposition, many Nationalists were in harmony with the ALP on tariff protection. Barnes again saw his responsibilities as being clearly with the worker—‘to provide employment for [Australian men and women] and prevent them from being victimized by the importation of the products of other countries whose general conditions are vastly below those of Australia . . . I am an out-and-out protectionist. I would protect the industries of this country from any possible competition’.[4]

The House of Representatives election of October 1929 resulted in a landslide to Labor, but with no election for the Senate the coalition parties in that house retained the majority they had held in the previous Parliament. Thus Barnes remained one of seven Labor senators of whom only Barnes himself and Senator Daly were in the new Scullin Cabinet. After his work on the Standing Committee on Public Works, Barnes was well placed to become Assistant Minister for Works and Railways, holding the position until March 1931.

Speaking during a ministerial statement in March 1930 he had referred to the need to establish the Commonwealth Bank on ‘a footing that will make it an instrument to be used by the people’, but modestly confessed that he was not ‘a financial expert’. On the matter of Sir Robert Gibson being called before the bar of the Senate he was laconic: ‘I have never known an instance of any person having been called as a witness to the bar of the Senate. Indeed, I am wondering where the bar of the Senate is’.[5]

In common with other leading ALP representatives, Barnes had regarded with increasing suspicion the efforts of non-Labor governments to regulate industry outside federal arbitration tribunals. In 1926 he had labelled the Bruce–Page Government’s Crimes Bill that authorised action against ‘unlawful’ and ‘revolutionary’ associations as ‘the most disgraceful [proposal] that has ever been brought before any legislature’. A lifelong advocate of arbitration, Barnes spoke out against Bruce’s attempt to discipline the militant unions. ‘I do not claim’, he said, ‘that [the Arbitration Act] is the last word in bringing about industrial peace, but I do claim that it is 100 per cent. better than anything which preceded it’. In August 1930, as Deputy Leader of the Government in the Senate, he was a member of the conference of managers of both houses responsible for having the much amended Conciliation and Arbitration Bill, which ensured that strikes and lockouts were again assured of legality, pass the Senate.

In March 1931 Barnes became Leader of the Government in the Senate, taking the place of Daly, who had been dropped from the Cabinet following a ministerial spill. Barnes was popular, straightforward, determined and sensible. He had been a sound deputy to his predecessor and stood firmly as the Scullin Government disintegrated between 1930 and 1931, his core strength acknowledged by George Pearce: ‘During all our fierce encounters in the Senate during those two stormy years he and I remained good personal friends’. Throughout, Barnes remained influential in the Caucus. Faced with the rise of the Country Party, in 1923 he chaired a meeting of federal Labor parliamentarians from rural constituencies to discuss the formation of a country wing of the Labor Party.[6]

With the defeat of the Scullin Government in December 1931, Barnes became Leader of the Opposition in the Senate, denying a rumour early in 1932 that there was a move to ‘oust’ him. Taking part in the tariff debates in November 1932 he argued that the Scullin Government’s tariff wall had placed Australia ‘on a fairly even keel’ but had been broken down by the Ottawa Agreement earlier in the year. Throughout 1933 he mounted a series of attacks on the lack of government action on unemployment. He urged the Lyons Government to undertake a more expansive program of capital works relating to commerce and defence. By 1935 he despaired at the extent of unemployment, reflected in the decline in AWU membership as many men could not afford membership fees. ‘Why, in the name of Heaven’, he exclaimed, ‘cannot our young men and young women find work in the land of their birth?’[7]

Barnes was a shrewd and independent politician though his opinions frequently reinforced party policies. He made no secret, for example, of his centralist views:

For many years I have cherished the hope that there will be one parliament to govern Australia, instead of six or seven different parliaments, as is the case now . . . The existence of so many parliaments is the chief cause of the friction which has been engendered. In a country as big as Australia, with its small population scattered, many a little Iberian village thinks itself greater than Rome.

An avowed supporter of the White Australia policy, on Aboriginal issues he reflected AWU policy—that Aboriginal people had to be paid the same as ‘white men’. A member of the Senate’s Regulations and Ordinances Committee, in 1932 he expressed concern during a disallowance motion debate that a Northern Territory ordinance requiring employers to pay Aboriginal drovers three pounds a week had been cut down to thirty shillings a week. He reminded employers that the regulations made it obligatory to pay Aboriginal drovers the same wages as ‘white men’. Far from wishing to suppress the views of political enemies Barnes sought to have them heard—if for no other reason than to turn their words and actions to his own advantage. Accused of being ‘soft’ on communism he retorted: ‘From time to time we read in the public press statements . . . which appear to me to be printed and published with the object of stirring up “dear old ladies” of both sexes and frightening them over a matter which it seems to me does not amount to much’.[8]

Barnes was defeated at the federal election of 1934. As he left the Senate the following year friends in Melbourne raised a testimonial, which included the presentation of a wallet of bank notes. On 23 October 1937 he stood again for the Senate and was re-elected, but died on 31 January of the following year in the Mercy Private Hospital in East Melbourne, achieving the curious distinction of being the first (and to date the only) senator-elect to cause a casual vacancy. Barnes was accorded a state funeral. As the procession moved to the Anglican section of the Melbourne General Cemetery, passing ‘thousands of bared heads’, it paused outside the Trades Hall where union leaders had gathered. A short time later, a wattle was planted over his grave, in a ceremony attended by Barnes’ grandson, then a boy of six. But today it is the AWU’s 1943 monument that marks Barnes’ last resting place.

The Bulletin, whose verses had given him so much pleasure when he humped his swag in the bush, now commented sadly: ‘The A.W.U. has lost John Barnes’. In the Senate one of his political opponents, James McLachlan, said: ‘He was the soul of honour; his word was his bond. Although a forceful speaker and an ardent champion of the cause he espoused, his speeches breathed the spirit of sweet reasonableness that was so characteristic of him.’[9] On 27 October 1898, when a labourer at Broken Hill, Barnes had married at Christ Church, Kapunda, Ellen Charlotte Camba Abbott, a farmer’s daughter. Ellen survived him, as did the six children of their marriage—Doris, Ellie May, Jessie, Jack Hamilton, Grace and Alice Mary.

A rugged individualist, described as a ‘rock-like figure . . . amid the currents and cross currents of Labor intrigue and politics’, Barnes retained many of the characteristics of his bushman beginnings throughout his lengthy political and trade union career. In 1923, enjoying a smoke in the Senate chamber, he questioned the President’s authority to stop him, an action that led to a presidential ruling that prevented any senator from erring in such a way again![10]

[1] The editor is grateful for information received from John Withell, grandson of John Barnes; Herald (Melb.), 31 Jan. 1938, p. 4; Australian Worker (Syd.), 22 May 1935, p. 10; Norma Marshall, ‘Barnes, John’, ADB, vol. 7; Information taken from conference and annual reports, AWU Records, Noel Butlin Archives Centre, ANU; Argus (Melb.), 1 Feb. 1938, p. 2; Bulletin (Syd.), 2 Feb. 1938, p. 18; Labor Call (Melb.), 3 July 1930, p. 8; Australian Worker (Syd.), 2 Feb. 1938, pp. 7–8; W. G. Spence, History of the A.W.U., The Worker Trustees, Sydney, 1961, p. 116; Mark Hearn and Harry Knowles, One Big Union: A History of the Australian Workers’ Union 1886–1994, CUP, Cambridge, 1996, p. 141; John Merritt, The Making of the AWU, OUP, Melbourne, 1986, pp. 227–30; John Robertson, J. H. Scullin: A Political Biography, UWA Press, Nedlands, WA, pp. 32–3; Patrick Weller and Beverley Lloyd (eds), Federal Executive Minutes 1915–1955, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1978, p. 44.

[2] CPD, 9 July 1913, pp. 5, 6; SMH, 25 Jan. 1923, p. 10; CPD, 15 Nov. 1918, p. 7903; Herald (Melb.), 21 June 1926, p. 6; CPD, 9 Sept. 1915, p. 6770, 18 June 1926, p. 3290; Senate, Journals, 25 June 1926; Aaron Wildavsky, The 1926 Referendum, F. W. Cheshire, Melbourne, 1958, pp. 51–3; Weller and Lloyd, Federal Executive Minutes 1915–1955, pp. 97, 137, 182.

[3] Herald (Melb.), 31 Oct. 1928, p. 6; CPD, 3 Oct. 1916, p. 9215; Herald (Melb.), 6 Jan. 1927, p. 6; CPD, 3 June 1914, p. 1710, 14 July 1926, p. 4107, 14 Sept. 1916, p. 8534, 18 Dec. 1918, p. 9705, 26 Sept. 1918, pp. 6394–5, 5 Mar. 1917, pp. 10982–6; Ernest Scott, Australia During the War, A & R, Sydney, 1943, pp. 638–40; CPD, 14 Dec. 1916, p. 9771.

[4] CPD, 19 Mar. 1920, p. 613, 20 Aug. 1924, pp. 3312–15; CPP, Joint Standing Committee on Public Works, reports, 1927, 1924, 1925; Geoffrey Sawer, Australian Federal Politics and Law 1901–1929, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1956, p. 239; Ulrich Ellis, The Country Party: A Political and Social History of the Party in New South Wales, Cheshire, Melbourne, 1958, pp. 217–19; CPD, 28 May 1926, p. 2435.

[5] Ross McMullin, The Light on the Hill: The Australian Labor Party 1891–1991, OUP, Melbourne, 1991, p. 152; SMH, 23 Oct. 1929, pp. 15, 16; Herald (Melb.), 14 June 1930, p. 5; CPD, 13 Mar. 1930, pp. 88–90, 14 Mar. 1930, pp. 147–9, 11 Dec. 1929, pp. 980–1, 1 May 1931, pp. 1538–41.

[6] CPD, 10 Mar. 1926, pp. 1451–5, 12 June 1928, pp. 5859–66, 4 Sept. 1929, pp. 501–2, 7 Aug. 1930, pp. 5528–9, 5618–19, 7 & 8 Aug. 1930, pp. 5560–2, 24 July 1931, pp. 4381–4; Geoffrey Sawer, Australian Federal Politics and Law 1929–1949, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1963, pp. 16–18; George Foster Pearce, Carpenter to Cabinet: Thirty-Seven Years of Parliament, Hutchinson & Co., London, 1951, p. 188; SMH, 13 July 1923, p. 8.

[7] Herald (Melb.), 23 Mar. 1932, p. 6, 24 Mar. 1932, p. 10; CPD, 17 Nov. 1932, p. 2473, 25 Oct. 1933, p. 3877, 28 Mar. 1935, p. 404, 10 Apr. 1935, p. 1168.

[8] CPD, 26 May 1933, p. 1883, 9 Apr. 1935, p. 1029, 2 Mar. 1932, pp. 450–3, 10 Nov. 1931, p. 1561.

[9] Australian Worker (Syd.), 22 May 1935, p. 10; Age (Melb.), 28 June 1935, p. 14; SMH, 28 June 1935, p. 12; Harry Evans (ed.), Odgers’ Australian Senate Practice, 10th edn, Department of the Senate, Canberra, 2001, p. 133; Labor Call (Melb.), 3 Feb. 1938, p. 1; Herald (Melb.), 1 Feb. 1938, p. 8, 2 Feb. 1938, p. 2; Labor Call (Melb.), 3 Mar. 1938, p. 3, 18 Feb. 1943, p. 10; SMH, 11 July 1938, p. 15; Australian Worker (Syd.), 9 Feb. 1938, p. 7; Bulletin (Syd.), 2 Feb. 1938, p. 18; CPD, 27 Apr. 1938, pp. 529–30.

[10] Herald (Melb.), 6 Jan. 1927, p. 6; CPD, 24 Aug. 1923, p. 3493; J. R. Odgers, Australian Senate Practice, 3rd edn, Commonwealth Government Printer, Canberra, 1967, p. 99; Rulings of the President of the Senate, the Hon. T. Givens, from 1913 to 1926, vol. 4, Government Printer, Melbourne, 1926, p. 12.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 2, 1929-1962, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic., 2004, pp. 91-96.