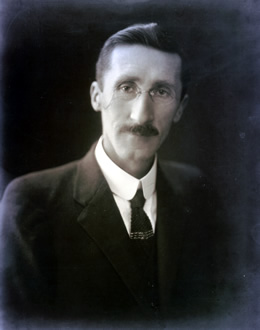

CHAPMAN, John Hedley (1879–1931)

Senator for South Australia, 1926–31 (Australian Country Party)

John Hedley Chapman was born at Jamestown, a small town north of Adelaide, on 16 December 1879. He was the only son of Sarah Jane, née Williams, and John Chapman, a farmer, whose grandfather, also John Chapman, had emigrated from Cornwall in 1845. John Hedley’s schooling commenced at the local Jamestown school (now Jamestown Community School) and was continued at Prince Alfred College in Adelaide. In 1895 Chapman took a position as junior clerk in the Jamestown branch of the National Bank of Australasia and rose to the position of assistant manager before he had to resign in 1903 following complications from a nasal operation. Despite a trip to England to see medical specialists, his health never really recovered. To provide him with an outdoor livelihood, in 1906 the family purchased ‘Cooyamoolta’, a property twenty miles from Port Lincoln, where he grew wheat and raised stud merino sheep. On 9 October 1909 he married Mary Isabelle Syme of Millswood, South Australia, in the Church of St George, Goodwood.

Chapman was acutely aware that conditions for farmers would not improve until they had a voice in the decision-making processes. The South Australian Farmers’ and Settlers’ Association, formed in 1915 as a pressure group to influence whatever party was in power, had his enthusiastic support. The association nominated its first parliamentary candidates in September 1917 and was successful in winning two seats in the South Australian elections of 6 April in the following year, one for the House of Assembly and one in the Legislative Council, Chapman becoming a member for the Assembly seat of Flinders. He held the seat until his defeat at the 1924 elections, which saw Labor returned to power after the non-Labor vote was split by many three-cornered contests.[1]

As the sole Farmers’ and Settlers’ Association representative in the Assembly until 1921, Chapman realised that his influence would be limited. His first speech raised issues of concern to the farming interests he represented: improved road, rail and telecommunication links, schools, cheaper water, the lack of representation of farmers in the wheat marketing scheme, and monopolies in the supply of such farming necessities as superphosphate. These and associated matters, such as the viability of soldier settlement schemes, the water supply to the Eyre Peninsula and drought relief, remained key concerns during his six years in the House of Assembly.

After the 1921 elections Chapman was joined in the Assembly by three other Farmers’ and Settlers’ Association colleagues. The name ‘Country Party’ was adopted at this time, and Chapman became party Whip. The Chapman family lived in Adelaide for the parliamentary sessions as, despite their owning the first car on the Eyre Peninsula, the trip from Port Lincoln was challenging and involved the crossing of Spencer Gulf by punt. Cooyamoolta was sold in 1921, as the travelling became onerous for Chapman’s growing family and difficult to combine with his parliamentary duties. Following his defeat in 1924 Chapman engaged in property development in Goodwood Park and Lower Mitcham. Around this time, the family moved to 42 Northgate Street, Unley Park, where Chapman lived for the rest of his life.

In South Australia, as in other states prior to the 1925 federal election, collaborative agreements were made between the Country and Nationalist parties in order to ensure the return of the Bruce–Page Government. The South Australian state council of the Country Party Association agreed that its Senate candidates should be composed of two Nationalist Party nominees and one Country Party nominee, and selected Chapman. The preselection was controversial due to argument and counter-argument between the party and the Minister for Markets and Migration, Senator R. V. Wilson. At the federal election in November, at which the Bruce–Page Government was successful, Chapman was elected. In March 1926, he was one of a twelve-member committee appointed by the Australian Farmers’ Federal Organisation to draft a constitution for an ‘Australian Country Party Association’—in essence this would unite in a confederation the state organisations.[2]

Chapman was sworn on 1 July 1926, joining the last group of senators to sit in the Legislative Council chamber in the Victorian Parliament House. In March, Chapman asked the Leader of the Government in the Senate, George Pearce, to persuade ‘the imperial authorities’ to allow HMS Renown (bringing the Duke and Duchess of York to Australia for the opening of the federal Parliament House in Canberra) to call at South Australia. Alas for South Australia, Renown could not stop by Adelaide. According to a charming account of the occasion written later by Chapman’s wife, despite a chilly arrival in Canberra by train at 6 a.m. on the morning of 8 May 1927, the opening the next day was memorable:

Our Rose of York badges admitted us anywhere . . . The Duke and Duchess were preceded by a picked bodyguard drawn from the Navy, Army and Air Forces . . . led by a magnificent Highlander. My frock, a peach coloured ensemble, with fur collar and cuffs, cost £18/18/-, a pretty big price in those days . . . In the evening there was a reception. Our names were announced as we passed the Duke and Duchess. We bowed. Not many women curtsied.[3]

In the Senate Chapman devoted his political energy to promoting his state and its primary industries. He referred to the fact that the Nationalists had not absorbed the Country Party, which had not ‘in any way lost its identity’. Supporting the States Grants Bill in March 1927, he proclaimed that ‘no whip had ever been cracked over him’. From the evidence of his parliamentary speeches, Chapman was a direct and informed speaker, not noted for rhetorical flourishes or for abuse of opponents. He was prepared to explore issues in depth, a habit attested to by senatorial colleagues, and by his wife, who wrote that Chapman ‘was more often than not up till 2 a.m. studying and answering correspondence when he was home’.[4]

Chapman’s personal experience of farming on marginal land influenced his contribution to debate. As he said: ‘I drove my own stripper, and rode on my own plough, when wool was about 9d. 10d. or 11d. per lb., and wheat was about 3s. 3d. or 3s. 6d. a bushel’. On the Development and Migration Bill 1926, he supported the proposed allocation of land to assisted migrants but stressed that successful settlement depended on migrants being experienced in farming and in possessing some capital. He considered a tax on roads ultimately would assist primary producers. He kept an ever-watchful eye for increases in duties on farming necessities, protesting vigorously, though on occasion ineffectively, for their reduction. He considered the piano as essential for the social well-being of farming families, asking specific questions about duties on imported pianos and the value of the Australian‑made product.[5]

On the Wine Export Bounty bills of 1927 and 1928, he argued for maintaining the bounty paid on export wine to keep the industry going and to prevent soldier settler grape-growers from being ruined. In 1929 he supported the Wine Overseas Marketing Bill as an attempt to stabilise the wine industry, despite his doubts about placing control of the industry in the hands of wine-makers. Later in 1929 Chapman, at his own expense, went with his wife to England and Europe to investigate the marketing of Australia’s primary produce.

In June 1930 the Labor Government introduced into the Senate its Wheat Marketing Bill on which the Country Party was divided. Despite having been personally affected by the vagaries of the wartime wheat pool scheme, Chapman, speaking on the second reading of the bill, concluded that a compulsory wheat pool for marketing surplus Australian wheat was inevitable. Homing in on the central point of difference within the Country Party, he said that the measure was not a form of ‘socialization’ but ‘cooperation’, designed to give the farmers a voice in price-fixing. The bill was defeated when Country Party senators Johnston and Carroll withdrew their support. When the Wheat Advances Bill (which allowed for Commonwealth financial advances of 3s. per bushel) came before the Senate in 1930, Chapman not only indicated his support but signalled he would have little to say during the bill’s committee stages—where ultimately numerous amendments were made.[6]

A Methodist, John Hedley Chapman was a tall, thin man who endured a constant struggle with poor health. He died at Sister Rowe’s Private Hospital in Wakefield Street, Adelaide, on 14 March 1931 while still a senator, and was buried in the West Terrace Cemetery beside his young son, who had died at four years of age. His wife, and children, Hedley Douglas, William Glanville, Shirley Wrathall, Alison Mary, and Geoffrey Flinders, survived him. Chapman had not lived to see the Wheat Bounty Bill, which provided a bounty of 4½d. a bushel on wheat, pass the Senate in October, but he did see his son, William Glanville, awarded an Angas Engineering Exhibition by the University of Adelaide in 1930.

A controversy over the filling of the casual vacancy occasioned by Chapman’s death occurred when, at the joint sitting of the South Australian Parliament, the Labor Party defied a doubtful convention, and successfully voted in one of its own, Henry Kneebone. But political manoevering was put aside for a brief interlude during the valedictory speeches for Chapman in March 1931. According to Senator Barnes, Chapman had been ‘a general favourite’. He had been also a true representative of that group of wheat farmers whose activities led to the formation of the Country Party. Senator Hedley Grant Pearson Chapman, who entered the Senate in 1987, is John Hedley’s great-nephew.[7]

[1] M. I. Chapman, Memoirs (unpub.), pp. 10–11; The editor is indebted to Mrs Shirley Twist (Chapman’s daughter), the National Australia Bank Group Archives and the Jamestown Public School, South Australia, for information; Ulrich Ellis, A History of the Australian Country Party, MUP, Parkville, Vic., 1963, pp. 33, 38.

[2] SAPD, 20 Aug. 1918, pp. 269–74; Ellis, A History of the Australian Country Party, pp. 73, 121–2, 137; Who’s Who in Adelaide, South Australia, 1921–22, Associated Publishing Service, Adelaide, [1923], p. 68; Chapman, Memoirs, pp. 18–21; Earle Page, Truant Surgeon, ed. Ann Mozley, A & R, Sydney, 1963, pp. 172–3; Ellis, A History of the Australian Country Party, pp. 141–3.

[3] CPD, 1 July 1926, pp. 3680–1, 21 Mar. 1927, pp. 699–700, 22 Mar. 1927 pp. 789–90; Chapman, Memoirs, p. 24.

[4] CPD, 4 Dec. 1929, pp. 638–42, 4 Aug. 1926, pp. 4843–5, 17 Mar. 1927, p. 565, 5 Dec. 1930, pp. 1043–6; Chapman, Memoirs, p. 22.

[5] CPD, 5 Dec. 1930, p. 1045, 14 Jul. 1926, pp. 4078–81, 11 Aug 1926, p. 5217, 22 Mar. 1928, pp. 4032–3, 4037, 21 Mar. 1928, pp. 3956–7, 15 Dec. 1927, p. 3261.

[6] CPD, 23 Mar. 1927, pp. 924–5, 17 May 1928, pp. 4971–4, 19 Mar. 1929, pp. 1384–90, 17 Mar. 1931, p. 266, 25 June 1930, pp. 3184–92, 26 June 1930, pp. 3269–70, 4 July 1930, p. 3716; Geoffrey Sawer, Australian Federal Politics and Law 1929–1949, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1963, pp. 17–18; CPD, 17 Dec. 1930, p. 1588.

[7] Advertiser and Register (Adel.), 16 Mar. 1931, pp. 3, 11; Chapman, Memoirs, p. 13; CPD, 18 Mar. 1931, pp. 322–4; B. D. Graham, ‘Graziers in Politics: 1917 to 1929’, Historical Studies, May 1959, pp. 383–91; Greg Whitwell and Diane Sydenham, A Shared Harvest: The Australian Wheat Industry, 1939–1989, Department of Economic History, University of Melbourne, 1991, pp. 40–1; CPD, 21 Oct. 1987, pp. 1080–1.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 2, 1929-1962, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic., 2004, pp. 250-254.

National Library of Australia

nla.pic-an23646747

Commonwealth Parliament

Senator, SA, 1926–31

South Australian Parliament

Member of the House of Assembly, Flinders, 1918–24