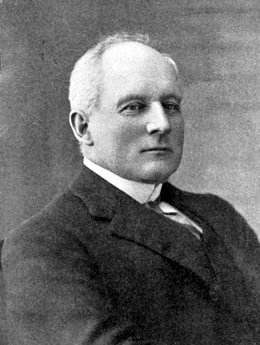

BOYDELL, Charles Broughton (1856–1919)

Clerk of the Senate, 1908–16

Although there is no evidence that Charles Broughton Boydell had strong religious convictions, or indeed that he was very religious at all, he had excellent family connections with the Church of England. His mother was Mary Phoebe Broughton, elder daughter of the Rt Rev. William Grant Broughton, DD, one-time East India Company official, and chaplain of the Tower of London.

Charles’ father, William Barker Boydell, came from Caergwrle in County Durham. The Boydell family had been resident in Normandy from the eleventh century, when they were known as de Boydell, and in Cheshire from the twelfth, the family’s landholdings being recorded in the Domesday Book. Noted simply in family records as a pioneer, William, in 1836, at the age of eighteen, embarked for Australia on the Camden. Also on board was the newly consecrated Bishop Broughton, his wife and their two daughters, Emily and Mary Phoebe (known as Phoebe), who were making a return trip to Australia after spending several years in England. William Barker and Mary Phoebe were married on 18 April 1844 at St James’ Church in Sydney, where Mary’s father had been installed as the first Anglican bishop of Australia in June 1836.

William and Phoebe settled on land purchased on the Allyn River at Upper Paterson in New South Wales. William named the estate ‘Caergwrle’, and on it he followed pastoral and agricultural pursuits. William and Phoebe had six sons and four daughters. Charles Broughton Boydell was the fourth-born son, entering the world at Upper Allyn on 2 May 1856. Two of his brothers were educated at The King’s School, Parramatta, which Bishop Broughton had established in 1831. Despite accounts suggesting he was a student at The King’s School, Charles was not—the school was closed from 1864 to 1868 due to the return to England of its headmaster, the Rev. Frederick Armitage, and the resignation of an assistant master, Mr L. J. Trollope. It is not known where Charles was educated.

On 1 February 1873, Charles began full-time employment as an assistant Clerk in the New South Wales Legislative Assembly. On 29 December 1880, he married at St Paul’s, Paterson, Madeline Rose Arnold, daughter of a former Speaker of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly, though there is no indication that nepotism was involved (or indeed needed) in order to further Charles’ career.

Boydell remained in the Legislative Assembly until 1901, gaining experience in parliamentary procedure and administration as it applied to an Australian Parliament at that time. It is probable that he also assisted at the meetings of the National Australasian Convention held in the Legislative Assembly in Sydney in 1891 and perhaps at the Sydney session of the 1897–98 Australasian Federal Convention, also held in the Assembly chamber. (As the federal conventions were conducted in accordance with established parliamentary practice, the specialised talents of the Clerks, notably E. G. Blackmore, were in demand.)[1]

When the intelligent and hard-working Boydell decided to transfer to the new Commonwealth Parliament in Melbourne in April 1901, he brought with him the essential experience required of the Clerks and their assistants. He commenced in a senior position, Clerk-Assistant in the House of Representatives, on 1 May. He stayed in the House only until 8 July, when he transferred to the Senate with the same rank. On 17 June 1907, Boydell became acting Clerk of the Parliaments and on 1 July 1908, Clerk of the Senate.

His sixteen-year career in the Federal Parliament covered a formative and turbulent period in Australian politics. It saw the establishment of the legislative framework for the Commonwealth and included the ministries of seven prime ministers. Boydell worked for an amorphous congregation of men who reflected the first enthusiasms of Australians for their new political structure. He witnessed the emergence and development at the federal level of the two major political parties. From his vantage point as Clerk of the Senate between 1908 and 1916, he watched the playing out in the Parliament of great national events, especially the trauma of World War I and the ensuing conscription debates, with the split in the Labor Party and the lead-up to the establishment of the Nationalists.

Boydell’s task as chief executive officer of the Department of the Senate was the provision of procedural and constitutional advice to senators and to the three Presidents he served—Albert Gould, Henry Turley and Thomas Givens. His principal concern was with the procedures by which the Senate governed itself, especially in relation to the Constitution, Senate standing orders and President’s rulings.

In the development of parliamentary administration and procedure, Charles Boydell has some achievements to his credit. One of these was the termination of the anachronistic position of Clerk of the Parliaments. From 1907 to 1908, Boydell acted as Clerk of the Senate during the absence (because of ill-health) of the incumbent Clerk, E. G. Blackmore. The Clerk of the House of Representatives, Charles Gavan Duffy, challenged Boydell’s right to act also as Clerk of the Parliaments (a position held simultaneously by Blackmore as Clerk of the Senate), arguing that he himself was senior to Boydell and should have the title. The President of the Senate, Albert Gould, protested to the Prime Minister, Alfred Deakin, that the title and position should remain with the senior Senate official. In the ensuing debate, however, the Government decided that there were no particular duties attached to the position that could not be performed by the Clerk of the Senate, and the title and position of Clerk of the Parliaments duly disappeared.

In 1908, Boydell was a witness to the joint select committee appointed to inquire into the procedure for the trial and punishment of persons charged with breach of privilege. Sir John Quick was chairman of the committee. Witnesses who provided evidence to the committee also included Charles Gavan Duffy, R. R. Garran, Secretary to the Attorney-General’s department and Parliamentary Draftsman, and Professor Harrison Moore of the University of Melbourne Law School. In his evidence, Boydell referred to his experience in the New South Wales legislature and expressed his opinion that there should be federal legislation on the matter. (It was not until 1987 that a Parliamentary Privileges Act became law.)[2]

Boydell was instrumental in establishing guidelines for appointments and promotions to, and within, the parliamentary departments. In 1908, the immediate issue had been the question of the replacement of Blackmore as Clerk of the Parliaments, but Boydell’s recommendations to the President of the Senate had far wider implications. He used the uncertain relationship between the Parliament and the public service to considerable advantage. He stressed the primacy of promotions from within a parliamentary department, and the importance of seniority over efficiency: ‘I have the advantage by at least five years over any other officer of the Commonwealth Parliament’, Boydell informed Senator Gould. He went on to state that ‘if any officer from any other Department were appointed to the position of Clerk, he would necessarily be less familiar with the practice and procedure of the Senate’.

Boydell resisted the first attempt by government (there would be others, though none successful) to consolidate the separate parliamentary departments—those of the Senate, the House of Representatives, Hansard, the Parliamentary Library and the Joint House Committee (the latter being responsible for catering and amenities)—into one. The challenge was mounted in June 1910, when the Prime Minister, Andrew Fisher, wrote to the Attorney-General, W. M. Hughes, asking him to look into the question of the organisation of these departments. There was much correspondence back and forth, from which the view emerged that consolidation should take place. This decision, however, was never acted on. It is not known whether or not Boydell and his senior colleagues in both Houses enlisted the support of the Presiding Officers to defeat the Government’s plan, which, had it eventuated, would have compromised the Clerk’s own territorial interests.

Perhaps Boydell’s most valuable contribution to Parliament was his Notes on the Practice and Procedure of the Senate in Relation to Appropriation, Taxation, and Other Money Bills Together with Standing Orders and Presidents’ Rulings. Published in September 1911, the Notes included case studies drawn from parliamentary practice between 1901 and 1910. They were a valuable guide to cases in which the Senate had exercised its right of requesting amendments to money bills as provided in section 53 of the Constitution, and to Presidents’ rulings on the subject’.[3]

There is little on record about Boydell’s life outside Parliament. His family life seems to have been conventional enough. He remained happily married, and he and Madeline had five sons, William, Charles, Frederic, Richard and John. Frederic took a commission and served in World War I. Charles Boydell’s younger brother, Sydney Grant Boydell, achieved prominence as Clerk of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly (1927–30), where his expertise on parliamentary procedure and practice was sought by members of the Assembly. Sydney was also active as a governor and honorary secretary of The Kings’ School.

Charles Boydell retired from the Senate (after taking six months sick leave on full pay) on 1 July 1917. He died at ‘Oakfield’, his home in the Melbourne suburb of South Yarra, on 4 February 1919, and was buried at the Brighton General Cemetery the following day. Boydell’s wife and four of his sons—William, Frederic, Richard and John—survived him. At the time of Boydell’s retirement as Clerk of the Senate, Thomas Givens had referred to his ‘many years of good and valued service’, describing him as ‘a gentleman to whom we all owe a deep debt of gratitude’.[4]

[1] Barbara Treacy, The Line to Ellen: A Millennium of Boydells, Brolga Press, Gundaroo, NSW, 1997, pp. 146–147; P. C. Mowle, A Genealogical History of Pioneer Families of Australia, A & R, Sydney, 1969, pp. 28–30; Lloyd Waddy, The King’s School 1831–1981: An Account, Council of the King’s School, Parramatta, 1981, pp. 13–22; G. N. Hawker, The Parliament of New South Wales 1856–1965, Government Printer, Ultimo, NSW, 1971, p. 130.

[2] Gavin Souter, Acts of Parliament, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1988, p. 97; CPP, Report of the joint select committee on parliamentary powers, privileges, or immunities, 1908; G. S. Reid and Martyn Forrest, Australia’s Commonwealth Parliament 1901–1988, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1989, pp. 259–261.

[3] Memorandum, Boydell to Senator A. J. Gould, 3 June 1908, G. S. Reid Papers, MS 8371, NLA; Reid and Forrest, Australia’s Commonwealth Parliament, pp. 408–409; CPP, Report of the select committee on Senate officials, 1921; Charles Broughton Boydell, Notes on the Practice and Procedure of the Senate in Relation to Appropriation, Taxation, and Other Money Bills Together with Standing Orders and Presidents’ Rulings, Victorian Government Printer, Melbourne, 1911, p. 7.

[4] CPD, 20 December 1916, pp. 10267–10269, 9 February 1917, pp. 10377–10380; Argus (Melbourne), 5 February 1919, p. 6.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 382-386.