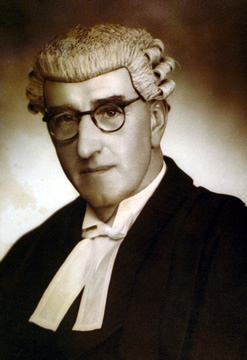

EDWARDS, John Ernest (1890–1958)

Clerk of the Senate, 1942–55

‘Without its permanent administrative officials’, wrote the journalist Warren Denning in 1946, ‘Parliament would be a rudderless ship, a ship of state with many captains, lots of passengers, but no crew’. During his forty years as a parliamentary officer, John Ernest Edwards made a distinctive contribution to parliamentary government as a member of that ‘crew’ through his ‘mastery and knowledge of all forms of parliamentary procedure’ and as an accomplished expositor of Senate practice.

Edwards was born in the Victorian spa town of Daylesford on 21 July 1890, the son of John Edwards, painter and carpenter, and Louisa Lovelock, née Verey. The Edwards were devout Methodists, John senior serving as a superintendent of the local sabbath school and a church trustee. John Ernest was educated at Daylesford State School and Melbourne’s University High School.[1] He entered the Commonwealth Public Service on 1 September 1911 as a clerk, 5th class, in the Public Service Commissioner’s Office in Melbourne, transferring to the Prime Minister’s Department on 1 August 1913 to act as secretary to the near‑blind Leader of the Opposition in the Senate, Gregor McGregor. During 1915 he served as secretary to the Attorney‑General, William Morris Hughes.

In July 1915 Edwards became a parliamentary officer in the Department of the Senate, appointed as a clerk and shorthand writer. In 1920, he was promoted to the position of Clerk of the Papers and by 1927 was Clerk of the Records and Papers. From 1920 he kept news clippings on parliamentary subjects, pasting them into a ‘News and other Cuttings’ book, embossed with the title ‘Clerk of the Papers’. He went on to serve as Usher of the Black Rod, Clerk of Committees, and accountant. On 1 January 1939 he was appointed Clerk‑Assistant, serving until December 1942. During this period he was also secretary of the Joint House Department. He served as Clerk of the Senate from December 1942 until his retirement on 20 July 1955.[2]

When the Commonwealth seat of government moved to Canberra in 1927, it fell to Edwards, as Clerk of the Records and Papers, to supervise the transfer of the Department of the Senate’s files from Melbourne. Edwards told the Age that anyone who enjoyed country life would probably like living in Canberra, whereas those of a more urban temperament might find the bush capital ‘fairly dull’ at first. Edwards himself may or may not have found Canberra dull, but it is obvious that he continued to enjoy his professional life, and made good use of the evolving Parliamentary Library, as can be seen from his ‘Where is it?’ book, in which, in his neat and careful hand, he made succinct notes on issues and books important in his work.[3]

During the late 1930s Edwards began to write articles for various journals, his first on a highly topical subject, ‘Control of Delegated Legislation in the Australian Senate’, published in the Journal of the Society of Clerks‑at‑the‑Table in Empire Parliaments in 1938, the Senate’s Regulations and Ordinances Committee having been established six years previously. He would continue as an occasional contributor to the journal—on proportional representation in 1948, the enlargement of the Parliament in 1950, on bills the Senate may or may not amend in 1952, and in 1951, with the Clerk of the House of Representatives, Frank Green, on banking legislation and the simultaneous dissolution of that year. He was also a contributor to the Australian Quarterly.[4]

In 1945 Edwards wrote a brief guide to Parliament entitled Parliament and How It Works, probably intended, in the main, for the use of new senators, and visitors to the Parliament. The monograph,whichwas regularly updated until 1951, had the support of the President of the Senate, Gordon Brown, who contributed a foreword to each edition in which he noted how ‘instructively and entertainingly’ the Clerk had performed his task. Edwards had the ability to write specialised information for academic publications, but also to make such information accessible to the layman. His booklet appears to be the first attempt at providing information on the Parliament to the public.[5]

In 1950 Edwards was called as a witness before the SelectCommittee on theConstitution Alteration (Avoidance of Double Dissolution Deadlocks) Bill. He proposed, as did the former Clerk of the Senate, R. A. Broinowski, that the method of resolving deadlocks between the Senate and the House of Representatives, as provided for in section 57 of the Constitution, required revision. Edwards and Broinowski proposed that bills in dispute should be referred to a joint sitting (at which the issue should not be resolved by mere voting strength) and if this failed the people should have the opportunity to decide by referendum. The referendum proposal was included in the select committee’s recommendations, though no further action was taken as the committee was composed of opposition senators only and the Government showed no inclination to follow its proposals.

Edwards’ work in the chamber prior to the simultaneous dissolution of March 1951 was not easy. After the election of the Menzies Government in 1949, the Labor Opposition in the Senate was in a majority, but anxious to avoid a simultaneous dissolution of the two houses. Senators on both sides exploited the standing orders to gain tactical advantage. (In 1955, President McMullin considered that Edwards emerged from this period ‘with enhanced prestige and respect’.) In 1951 the Hansard Society’s Parliamentary Affairs published Edwards’ article, ‘The Double Dissolution as a Political Weapon’, which concluded with what could have been interpreted as a warning to the Menzies Government: ‘. . . a Government which deliberately sets out to provoke a double dissolution is wielding a dangerous weapon. In using it to injure its opponents it must injure its own supporters as well. By risking defeat at the hands of the electors it may commit political suicide’.

Edwards was soon faced with an issue closer to home. The Appropriation Bill 1952–53 included a proposal that the Clerk of the House of Representatives should receive an annual salary £100 higher than that of the Clerk of the Senate. There had been a similar proposal in 1921. On each occasion the initiative failed; in 1952 because, as the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate, N. E. McKenna, put it, ‘this matter affects the prestige of this chamber in relation to the House of Representatives . . . and no distinction should be made between these two positions’.

In March 1953, with the Menzies Government troubled by the threat of losing its Senate majority, Edwards had to deal with another attempt by the Public Service Board to place Senate staff salaries below those of the House of Representatives. At the instigation of the Speaker, an acting assistant commissioner of the Public Service Board (L. O. Brown) undertook a review of staffing in the parliamentary departments. Faced with the threat of classifications for third division positions in the Department of the Senate being placed at about one scale lower than those for the House of Representatives, Edwards argued firmly for equality in pay between all levels in both houses, although on this occasion the matter did not directly concern service conditions for the Clerks themselves. While in the end the issue seems to have fizzled out, Edwards probably deserves considerable credit for withstanding what appears to have been a political attempt to downgrade the place of Senate officials, thus potentially diminishing the Senate itself.[6]

As Clerk, Edwards was, ipso facto, secretary of the Standing Orders Committee. Late in 1950, anticipating a possible point of order on a motion to appoint a select committee on national service in the defence force, he referred to the Senate’s power ‘to appoint a select committee to inquire into almost any subject’. Edwards stressed that Senate standing orders and practice would permit this proposed committee to operate ‘notwithstanding the adjournment or prorogation of the Parliament’. ‘The Senate’, he concluded, ‘is complete master of its own procedure’. No point of order was taken, and the committee was appointed.

He was undeniably an influential Clerk with a high degree of constitutional and procedural knowledge who ensured that he had also a team of professional parliamentary officers. The most notable of his subordinates was J. R. Odgers. On 15 February 1954 Edwards read the Proclamation at the opening of the Commonwealth Parliament by Queen Elizabeth II, the first such occasion in Australia. In poor health, he was forced to take leave in July. Senators were as one in wishing this ‘philosopher, friend and guide’ a quick recovery. But it was not to be, and Edwards spent most of his last year in office on sick leave. Hence his absence from the Senate chamber on 9 June 1955, when handsome retirement tributes were paid to him. The President, Alister McMullin, praised the Clerk’s ‘remarkable’ knowledge of Senate procedure and recalled Edwards’ ‘sound advice, encouragement and guidance’ during his early days as President. Senator Neil O’Sullivan, the Leader of the Government in the Senate, described Edwards as being ‘ever the champion of the rights and legislative powers of the Senate’, while Senator McKenna, stressed that the Clerk had ‘the deep respect and the very real regard of every member of the Opposition in this chamber’.

Edwards died at his home in Canberra on 27 March 1958 and was cremated at Sydney’s Northern Suburbs Crematorium. On 2 December 1916, he had married music teacher Constance McArthur Easton, in a Methodist ceremony at Moonee Ponds, Melbourne. That he welcomed women into the Senate is clear from his letter to Senator Agnes Robertson in 1949 when he wrote that ‘the much‑maligned Senate has been paid a graceful compliment by the electors giving us four lady members, while the other House is reduced to one’. Edwards’ wife and his son Neil Russell, an only child, survived him. His recreations had included tennis, gardening, reading, chess and music, Senator Condon Byrne noting an ‘apparent asceticism’ in Edwards’ character, though conceding that his work in the Senate had been his life, a view with which Edwards would have agreed:

To serve as an Officer of Parliament is a unique and fascinating occupation. One can feel that he is present at the making of history. He can watch the play of political passions, the ebb and flow of great movements, the pathos and tragedy of lost causes and personal defeats, the rise and fall of personalities, and so on. He can enjoy an election campaign as an interested spectator, watching the fall of the mighty with joy or regret, according to his inmost feelings which he keeps strictly to himself. If he reaches the retiring age he can write his reminiscences if he feels so inclined. It is a most satisfying life’s experience.[7]

[1] Warren Denning, Inside Parliament, Australasian Publishing Co., Sydney, 1946, p. 200; CPD, 9 June 1955, p. 801, 27 Mar. 1958, p. 461; [R. Hocking], The Story of Early Methodism in Daylesford by a Pioneer,G. A. Green, Melbourne, 1910, pp. 8, 9, 25, 28, 35–7.

[2] CPD, 9 June 1955, p. 799; Commonwealth Government Gazette,17 July 1915; J. E. Edwards, ‘News and other Cuttings’, Department of the Senate, [1920].

[3] Age (Melb.), 28 Feb. 1927, p. 8; J. E. Edwards, ‘Where is it?’, Department of the Senate, 1935.

[4] J. E. Edwards, ‘Control of Delegated Legislation in the Australian Senate’, ‘P. R.: Application of the System in Electing the Senate of the Commonwealth of Australia’, ‘Bills which the Australian Senate May or May Not Amend’, Journal of the Society of Clerks–at-the–Table in Empire Parliaments, vol. 7, 1938, vol. 17, 1948, vol. 21, 1952; J. E. Edwards and F. C. Green, ‘Australia: Resulting Changes in 1950 Following the Enlargement of Commonwealth Parliament’, ‘Australian Banking Legislation and the Double Dissolution’, Journal of the Society of Clerks–at-the–Table in Empire Parliaments, vol. 19, 1950, vol. 20, 1951; J. E. Edwards, ‘The Powers of the Australian Senate in Relation to Money Bills’, Australian Quarterly, Sept. 1943.

[5] John E. Edwards, Parliament and How It Works, Canberra, 1945, p. [3].

[6] CPP, Select Committee on the Constitution Alteration (Avoidance of Double Dissolution Deadlocks) Bill, report, 1950; J. R. Odgers, Australian Senate Practice, 1st edn, Government Printer, Canberra, 1953, pp. 18–19, 39; CPD,9 June 1955, pp. 799–802; J. E. Edwards, ‘The Double Dissolution as a Political Weapon’, Parliamentary Affairs (Lond.), Winter 1950, pp. 92–105;CPD, 1 Oct. 1952, p. 2407; G. S. Reid Papers, MS 8371, box 26, folder 16/3/6, NLA; G. S. Reid and Martyn Forrest, Australia’s Commonwealth Parliament 1901–1988, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1989, pp. 429–31.

[7] Odgers, Australian Senate Practice, 1st edn, p. 195; CPD, 9 June 1955, pp. 799–802, 27 Mar. 1958, p. 461, 15 Feb. 1954, pp. 5–7, 4 Aug. 1954, pp. 21, 24; Letter, Edwards to Agnes Robertson, 30 Dec. 1949, Correspondence file, Department of the Senate; CPD, 27 Mar. 1958, pp. 460–2, 9 June 1955, p. 800; CT, 28 Mar. 1958, p. 2; John E. Edwards, Parliament and How It Works, Canberra, 1951, p. 36.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 2, 1929-1962, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic., 2004, pp. 477-480.