COLLINGS, Joseph Silver (1865–1955)

Senator for Queensland, 1932–50 (Federal Labor Party; Australian Labor Party)

Democratic socialist, union organiser, Labor troubleshooter and administrator, Joseph Silver Collings was born on 11 May 1865 at Brighton, England, the son of free thinker, Joseph Silver Collings, storekeeper, and his wife, Mary Ann, née Dyke, a Quaker. Educated at Brighton Board School, Collings became an apprentice journalist on the Sussex Daily News but emigrated to Brisbane with his parents in 1883 on the Roma. A stint as a farm labourer and an unsuccessful venture as a selector at Mooloolah followed. He was employed as a clerk in E. T. Neighbour’s boot factory, and then managed a shoe shop in Fortitude Valley. He was secretary of the Queensland Boot and Shoe Manufacturers’ Association, settling a strike in May 1890 and, to the chagrin of his radical associates, facilitating the arrival and employment of southern scabs to break another strike in 1895. Here, in the formative period of Collings’ life, there lies a paradox that was solved to his own satisfaction by his moving into the structures of mainstream labour after the turn of the century. This aroused the ire of such lifelong radicals as E. H. Lane.

With his father, Collings was prominent in those radical quasi-religious and politico-social movements that gave a dynamic tinge to a Queensland society in the 1890s that, with the ‘Continuous Ministry’ in office, seemed devoid of both thrust and ideas. With the radical editor of the Worker, Henry Boote, the future premier of New South Wales, J. Dooley, the journalist, ‘Bob’ Ross, and Lane, Collings was a member of the Social Democratic Vanguard group, whose demise Lane blamed on Collings’ political opportunism and ‘flair for questionable things’. ‘This flamboyant individual’, wrote Lane, ‘has taken a leading part in a number of reactionary working class movements . . . [but] it is questionable if any of his . . . activities have been more discreditable than his betrayal of the Vanguard to a time-serving and power-seeking Labour Party’. Collings was, however, a more complex and enduring political personality than the ‘Cosme’ purists.[1]

When the great Queensland strike of 1912 occurred Collings moved into industrial activism in a major way as editor of the Official Bulletin. An effective street orator and a member of the Strike Committee, Collings, while now regarding mainstream labour as a fulfilling career path, was capable of moving large audiences to tears with his combination of radicalism and evangelism. The strike failed, however, and Collings’ commission as Justice of the Peace was revoked. With the feminist and political activist, Emma Miller, he made the last speech on 6 March 1912 when the strike was declared off. Yet from the ruins emerged the Daily Standard (1912), published by the Labour Daily Newspaper Company, of which Collings was provisional chairman of directors. Collings also became a foundation member and first president of the Queensland branch of the Federated Clerks’ Union of Australia.

His parliamentary aspirations were thwarted when he failed to capture Bowen (1888), Toombul (1899), Bulimba (1908, 1909) and Murilla (1915). Nevertheless Collings was a delegate to Queensland Labor-in-Politics conventions in 1905, 1913, 1916, 1918, 1920, 1926, 1929, 1932 and 1938. He was also a member of the central political executive of the Queensland Labor Party for most of the years between 1913 and 1932, and in 1927, 1930 and 1933 served as a Queensland delegate to the federal conference of the ALP. At the 1927 conference, Collings and the future Queensland premier, William Forgan Smith, moved successfully that the ALP platform be revised to encompass ‘the socialisation of industry, production, distribution and exchange’ by constitutional and parliamentary means and, inter alia, that the Commonwealth Bank be placed ‘in the hands of the people’. But his major contribution lay in his role as salaried organiser for the ALP between 1914 and 1915 and between 1919 and 1935. Using trains and riding a bicycle, Collings proved to be a most effective, dedicated and thorough ALP recruiter and publicist.[2] During the anti-conscription campaigns of 1916 and 1917, he played a leading role as both orator and organiser. As his bitter foe Lane remarked: ‘Collings was uncompromisingly anti-war and with his well‑known pugnacity and eloquence had severely castigated the war‑mongering anti‑conscriptionists’.

After several attempts by Labor to abolish the Queensland Legislative Council, Collings was appointed a member of an unpaid ‘suicide squad’ that forced through the abolition of the Council in 1922. Collings himself left the chamber on the fatal night loudly whistling the Dead March from Saul. Earlier, in his first speech, describing himself as ‘one of the hewers of wood and drawers of water’—‘one of the unfortunate individuals of whom the vested interests opposite have all the time been taking toll’—he stated:

The Labour party has a definite programme which will make for the simplification and cheapening of government. We hold that the six State Upper Houses and the Senate of the Federal Parliament should be abolished, because we recognise that, unless the Upper Chamber is going to say ‘Ditto’ to what the Lower House does, it will only be here for the purpose of thwarting the legislation put through by the party in power in the Lower House; and if it is going to say ‘Ditto’, then there is no need for it.

But, subsequently, Collings became the complete constitutional Lazarus so far as the Senate itself was concerned. After a speaking tour of New Zealand in 1923, he returned to his organisational duties concerned with the continuance of the Queensland Labor Government. In 1931, following the damaging splits in New South Wales Labor, both federal and state, Collings was appointed to act as organising secretary of a provisional New South Wales executive charged with the Augean task of dealing with Lang Labor’s control of the labour movement, and the challenge from the Depression-stimulated Communist Party of Australia. Although Collings’ efforts took ten years to bear electoral fruit, mainstream Labor’s assessments of him paint a vivid canvas of Collings at the politically advanced age of sixty-six years on the verge of entering the Senate. The Australian Worker, admittedly a sympathetic source and now edited by Boote, profiled Collings as one who ‘combines in the one individual intense practicality and intense idealism’. Another newspaper editor remarked: ‘When Joe Collings enters my room the sunshine seems always to come with him’. Collings himself was the master of the apt quotation, be it in Cabinet, on the hustings, or in committee, with such tidbits as ‘My inferiors CAN not insult me, my superiors WILL not’; ‘Those who tell “White” lies soon become color blind’; and ‘First be sure you’re right then go ahead and see if you are’—all were characteristic of the man.[3]

Collings was first elected to the Senate in December 1931 when he stood as a Federal Labor Party candidate in order to separate himself from Lang Labor. He was re-elected in 1937 and 1943. Refusing to take the oath of allegiance, he made an affirmation on each occasion a new Parliament was inaugurated. Colourful and controversial, he relished interjections, narking other senators. At times he took an independent stance. He spoke often—and passionately—about Labor ideology and people. He took great exception to a report on the parliamentary departments made by J. T. Pinner, a Public Service Board official, seeing it as a ‘puerile and undignified’ invasion of parliamentary rights. Governors-General were ‘imported gentry’. The British parliamentary system was the best in the world. He did not mince matters when he spoke against the Lyons Government’s Financial Emergency Bill in September 1932: ‘Social welfare legislation has always met with the same cowardly criticism from those who are not in need of it’. He objected to the reduction proposed for parliamentary allowances on the grounds that it was ‘increasingly difficult for the representatives of the working class to become members of this Parliament, and to maintain themselves in Canberra’. In 1933, Collings and J. V. MacDonald stood apart from other Labor senators in their support of the Lyons Government’s Commonwealth Public Service Bill. The bill provided for the recruitment of university graduates to the public service without examination. (Geoffrey Sawer points out that Collings and MacDonald were ten years ahead of their time—the Labor left in 1933 still regarded education as the privilege of the wealthy.)

On 4 April 1935 Collings was unanimously elected by the Labor Caucus as Leader of the Opposition in the Senate; he was re-elected in 1938 and 1940. With the advent of John Curtin’s Labor Government he became Leader of the Government in the Senate (1941–43) and Minister for the Interior with responsibility for the newly established Allied Works Council (until February 1945). He was also president of the River Murray Commission (1941–45). On 13 July 1945 he moved from the Interior portfolio to become Vice-President of the Executive Council in the Chifley Government, stepping down from that position in November 1946, and from the Senate, at the age of eighty-five, on 30 June 1950.

As Minister for the Interior and Chairman of the Board of the Australian War Memorial, Collings was present at the opening of the Memorial on 11 November 1941—a somewhat ironic role given his consistent support for pacifism and his opposition to expenditure on defence. Indeed, in November 1932 he had argued during the debate on the Appropriation Bill’s defence estimates that if ‘we, as legislators, talked of peace as freely and as eloquently as some are prepared to talk of war, it would be unnecessary to vote money for defence purposes’. And in September 1935 he had outlined ALP policy regarding Italy’s invasion of Abyssinia: ‘the control of Abyssinia by any country’, he stated, ‘is not worth the loss of a single Australian life’.[4]

Although, as Minister for the Interior, Collings had a circumscribed role under E. G. Theodore as Director-General of the Allied Works Council (who supervised an immense program of military, munitions and quasi-civilian construction), he was shrewd enough to give the talented financier, ‘whose intellectual capacity he admired and whose economic and fiscal policies he approved’, his head. Essentially though, Collings was landlord and ‘mayor’ of the bush capital, Canberra. He objected to the belittling of Canberra—‘one of the noblest ideals ever conceived in the mind of man’. Canberra should be a cultural centre and all public servants should be placed there. Reduced to supervising Canberra’s absurd restrictions on the sale of liquor (including his own ban on Saturday afternoon liquor sales), organising the delivery of milk, firewood, ice, bread and meat (clashing in 1942 with the Victorian Builders’ Labourers’ Union over what he believed was incitement to hinder the war effort), Collings was also responsible for the Commonwealth electoral office and the Commonwealth railways.

As Senate leader he relished the cut and thrust of lively debate; a rare photograph depicts a gracious, civilised figure leading the thirty-year-old Perth schoolteacher, Dorothy Tangney, to her place on the Opposition benches as the first woman senator. Among the legislation Collings piloted through the Senate during his eight years as leader was the bill that provided for the establishment of the Australian National University. He considered this a proud moment but was less enthusiastic about introducing the Defence (Citizen Military Forces) Bill 1943 under which the Labor Government established limited conscription for service in the south-west Pacific. Domestically, he cultivated cabbages and roses in his Brisbane garden, fished from his shack at Sandgate and read the mysteries and thrillers of Dorothy L. Sayers, Edgar Wallace and Nicholas Blake. This literary fare was supplemented by Keynesian economics tomes.[5]

His 1946 leadership of Australia’s delegation to the International Labour Conference at Montreal was a prelude to the end of Collings’ long sojourn in the political limelight. He did not stand for the 1949 election. He had, in his Senate career, articulated those reformist labour values that owed as much to secular religiosity, shrewd service and bureaucratic skill as they did to profound philosophical convictions. The tributes to Collings, as Labor entered the political wilderness, were largely unfeigned. After paying tribute to his daughter Kate, ‘first, she has kept me out of gaol, and secondly, she has kept me alive’, Collings warned of ‘an entirely new world, in which scientists are developing methods of destroying human life that were previously beyond our comprehension’. ‘The question is’, he said, ‘whether we are going to use [scientific development] for destruction or construction . . . that imposes upon every one of us a new and greater responsibility’.

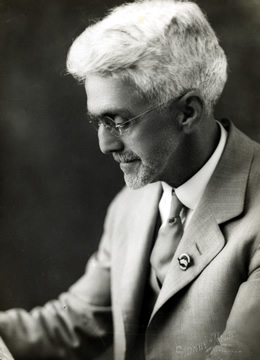

Collings retired to Brisbane where he died at his Brighton home on 20 June 1955. After a state funeral he was cremated at the Mt Thompson Crematorium, Holland Park. The panegyric was delivered by his friend, the atheist republican Dr J. V. Duhig, following a non-religious service. Collings was survived by Eric Harold and Kate, the remaining two of the six children of his registry office marriage on 26 December 1885 to Kate McInerney, a Roman Catholic, who predeceased him. A teetotaller, Collings enjoyed remarkable health and vitality. Slightly built, with silver hair, and a goatee, a bright, alert countenance and natty conservative suiting, he was called by R. G. Menzies ‘silver-haired and silver-tongued, silver Collings’, when Menzies wanted to be ‘civil’, and ‘Long John Silver’ when he did not. Chifley caught one aspect of Collings’ missionary rectitude when he observed at Collings’ Canberra farewell in 1949: ‘If he had not been such a fanatical Labor man he would have been a splendid conservative’.

Yet Collings had once remarked that it is ‘a bigger sin to starve than to steal in a land of plenty’. A similar sentiment was expressed in his favourite quotation:

If, in this fair land of ours,

There still remains one hungering child

Hungry for bread or flowers,

A stain upon your country’s honor lies

While one remains

Collings was more than a brilliant orator capable of reinforcing his revered leader’s ‘Light on the Hill’ message. A first-rate organiser, effective journalist, political conciliator and successful labour bureaucrat, Collings proved to be an outstanding senator during federal Labor’s wilderness years and wartime triumphs. As he declaimed in 1931: ‘Labor is my religion. I saw it born, I have watched it grow, and I have contributed to it a long life of willing service’. Not an ignoble, if somewhat personal, epitaph.[6]

[1] Joy Guyatt, ‘Collings, Joseph Silver’, ADB, vol. 8; Joy Guyatt, ‘Joseph Silver Collings, Labor Organiser, Journalist, Senator’, Labour History, Nov. 1980, pp. 83-8; Daily Standard (Brisb.), 5 May 1915, p. 3; Worker (Brisb.), 15 June 1895, p. 2, 22 June 1895, p. 3, 29 June 1895, p. 3, 13 July 1895, p. 2; Brisbane Courier and Observer, 15 Feb. 1912, p. 5; Pam Young, Proud to be a Rebel: The Life and Times of Emma Miller, UQP, St Lucia, Qld, 1991, pp. 33-5; Duncan Waterson, ‘Conflict, Conservation and Continuity: Queensland’s Continuous Ministries 1893-1899’, in Joanne Scott and Kay Saunders (eds), The World’s First Labor Government, Royal Historical Society of Queensland, Brisbane, 2001, pp. 18, 20, 30; E. H. Lane, Dawn to Dusk: Reminiscences of a Rebel, William Brooks & Co., Brisbane, 1939, pp. 55, 62–9; Ross Fitzgerald, From 1915 to the Early 1980s: A History of Queensland, UQP, St Lucia, Qld, 1984, pp. 4, 42.

[2] Official Bulletin (Brisb.), 1 Feb. 1912, p. 1, 8 Feb. 1912, p. 1, 6 Mar. 1912, p. 1; Young, Proud to be a Rebel, p. 188; D. J. Murphy (ed.), Labor in Politics: The State Labor Parties in Australia 1880–1920, UQP, St Lucia, Qld, 1975, pp. 180-4, 216–17; Labour Election Bulletin (Brisb.), 16 Apr. 1912, p. 4; D. J. Murphy, R. B. Joyce and Colin A. Hughes (eds), Labor in Power: The Labor Party and Governments in Queensland 1915–57, UQP, St Lucia, Qld, 1980, pp. 536-42; D. J. Murphy, T. J. Ryan, A Political Biography, UQP, St Lucia, Qld, 1990, pp. 92, 171–2, 402; Guyatt, ‘Joseph Silver Collings’, p. 85.

[3] Lane, Dawn to Dusk, p. 182; Daily Standard (Brisb.), 15 Sept. 1916, p. 5; Murphy, Joyce and Hughes, Labor in Power, pp. 107–10, 115; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 11 May 1955, p. 1; QPD, 26 Oct. 1921, p. 1837, 8 Dec. 1920, p. 562; Daily Standard (Brisb.), 15 Jan. 1932, p. 6; Australian Worker (Syd.), 13 May 1931, p. 6, 10 June 1931, p. 6, 20 May 1931, p. 6.

[4] Letter, Collings to the Clerk of the Senate, G. H. Monahan, 2 June 1932, Senate Registry File, A8161, NAA; CPD, 7 Sept. 1932, p. 238, 27 June 1933, pp. 2633–6, 18 June 1937, p. 51, 22 Oct. 1947, p. 1072, 28 Sept. 1932, pp. 806–8, 7 Dec., 1933, p. 5907; Geoffrey Sawer, Australian Federal Politics and Law 1929–1949, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1963, p. 55; Allied Works Council, reports, A5954/69, item 742/8, S954/69, item 748/8, NAA; CT, 12 Nov. 1941, p. 1; Michael McKernan, Here is Their Spirit: A History of the Australian War Memorial 1917–1990, UQP in association with the AWM, St Lucia, Qld, 1991, pp. 6-8; CPD, 9 Nov. 1932, pp. 2097-8; Lloyd Ross, John Curtin: A Biography, MUP, Carlton South, Vic., 1996, pp. 161-2; CPD, 23 Sept. 1935, p. 13.

[5] Ross Fitzgerald, “Red Ted”: The Life of E. G. Theodore, UQP, St Lucia, Qld, 1994, pp. 390-1; Guyatt, ‘Joseph Silver Collings’, p. 87; Australian Women’s Weekly (Syd.), 7 Aug. 1943, p. 10; SMH, 22 Sept. 1942, p. 4; Ann Millar, Trust the Women: Women in the Federal Parliament, Department of the Senate, Canberra, 1994, p. 135; CPD, 17 July 1946, pp. 2607–10, 17 Feb. 1943, pp. 751–61, 24 Aug. 1955, p. 4; John Faulkner and Stuart Macintyre (eds), True Believers: The Story of the Federal Parliamentary Labor Party, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW, 2001, p. 79.

[6] CPD, 18 July 1946, p. 2679, 31 May 1950, pp. 3416–19; Telegraph (Brisb.), 20 June 1955, p. 3; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 22 June 1955, p. 8; CPD, 18 June 1948, p. 2327; Guyatt, ‘Joseph Silver Collings’, p. 88; Gil Duthie, I Had 50,000 Bosses: Memoirs of a Labor Backbencher 1946–1975, A & R, Sydney, 1984, p. 85; D. J. Murphy, R. B. Joyce and Colin A. Hughes (eds), Prelude to Power: The Rise of the Labour Party in Queensland 1885–1915, Jacaranda Press, Milton, Qld, 1970, p. 136; Australian Worker (Syd.), 20 May 1931, p. 6, 10 June 1931, p. 6.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 2, 1929-1962, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic., 2004, pp. 358-363.