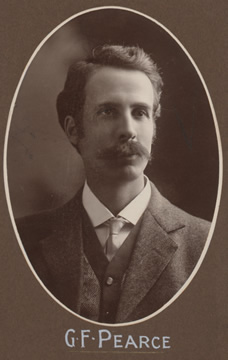

PEARCE, Sir George Foster (1870–1952)

Senator for Western Australia, 1901–38 (Labor Party; National Labour Party; Nationalist Party; United Australia Party)

In the next five years he became one of Perth’s most prominent trade unionists. Moderate in outlook, he preferred negotiation to confrontation, although the building strike he led in February 1897, which saw him blacklisted for some weeks, only enhanced his standing in the labour movement.[1] Three years later, in recognition of his efforts to bring about democratic and social reforms, he became the Trades and Labor Council’s nominee to contest the Senate election of 1901. He stood as a Free Trader, while Hugh de Largie, the nominee of goldfields’ labour organisations, stood as a Protectionist. Both were elected.

Most of the Commonwealth’s first politicians, regardless of their party affiliations, believed that the state should take responsibility for creating greater social justice and equality. There was room for argument over how far the state should go, but the principle was not seriously challenged. Pearce was at home in such an environment and he adjusted quickly to the life of a senator, becoming a powerful advocate for the policies of the Labor Party. He favoured a White Australia, a land tax to fund social welfare schemes, a people’s bank, the nationalisation of some large industries, a citizen defence force (as opposed to a standing army) and old-age pensions. And he was one of those Labor Free Traders who endorsed New Protection when it became obvious that they would have to live with tariffs.[2]

He served on the important Select Committee on the Provision for Old-Age Pensions in 1904, having won himself a reputation as one of the Parliament’s rising young men. He was not included in Labor’s first ministry that year, but from 1908 to 1909 was Minister for Defence in the short-lived Fisher Government. From then on, until his defeat in 1937, he was to spend almost twenty-five years as a minister in Commonwealth governments, a record of ministerial service which surpasses that of any other senator.

He was an influential Leader of the Government in the Senate, first for the Labor Party, then for the non-Labor parties, and a formidable Leader of the Nationalist Opposition during the Scullin years. His intimate knowledge of Senate procedures underpinned his success in these roles, but he was also a consummate parliamentary performer. He remained calm and polite during his exchanges with opposition senators, and he had perfected the practice early in his ministerial career of treating all questions asked of him with the utmost seriousness. Anger or wit made little headway against his grave demeanour and he was seldom lured into a careless response.

In his first term as Minister for Defence, he began the process of building an Australian navy by ordering three torpedo-boat destroyers. During his second term (1910–13), he attended the 1911 Imperial Conference in London where he helped determine the relationship between the Royal Navy and the Royal Australian Navy. More significantly, he implemented the Australia-wide compulsory military training scheme recommended by Lord Kitchener in his 1910 report on Australia’s land defences. He also secured approval in 1912 for a military aviation school at Point Cook in Victoria. As Defence Minister during World War I he was primarily responsible for the transportation and provisioning of Australian troops. His other responsibilities included the censorship of news and, for seven months in 1916 (January–August), the duties of Acting Prime Minister. In 1919 he visited Britain to oversee the demobilisation of Australian troops. He represented Australia at the signing of the peace treaty with Austria at St Germain.

The ‘Men, Money and Markets’ policies of the Bruce–Page governments of the 1920s bore many signs of his influence. From 1921 to 1926, as Minister for Home and Territories, Pearce concentrated on fostering stronger growth of the federal capital, Canberra, by encouraging greater private capital investment there. He also sought to achieve increased Commonwealth–state cooperation in the management of immigration schemes, and to improve the development of Australia’s mandated territories of New Guinea and Papua. In 1926 Pearce was the driving force behind legislation that divided the Northern Territory into two parts—northern and central Australia—an ambitious attempt to improve the region’s productiveness that was to fail. This failure was largely because of the less than cooperative attitudes of the Western Australian and Queensland governments and the unavailability of the large amounts of capital necessary for the rejuvenation of the Territory’s pastoral industry. In 1931 the federal Labor Government re-established the Territory as one administrative entity.[3]

From 1926 to 1929, he was responsible for piloting through the Senate legislation that reconstituted the Institute of Science and Industry in 1926 as the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (now the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation). He was also responsible in 1926 for the passage of the legislation which established the Development and Migration Commission. In 1927 he led the Australian delegation to the League of Nations Assembly in Geneva. As Minister for External Affairs, in 1935 he reorganised the Department of External Affairs, when it became a separate, autonomous administrative entity (hitherto it had been a branch of the Prime Minister’s Department). Pearce also instituted reforms aimed at improving the training of External Affairs officers.

Considerable skill lay behind these ministerial achievements. As early as 1908–09, Pearce’s administrative ability was obvious. He was mindful of detail, prepared to accept advice, equally willing to take decisions when the need arose, and astute enough to adhere to routines in his working day, and to limit his office hours, so as to reduce the possibility of workloads affecting his health. In the 1920s and 1930s he was a formidable force in Cabinet. In 1965 Sir Robert Menzies remembered him as the ablest man he had encountered among the many ministers with whom he had worked. He attributed to Pearce an unrivalled capacity for analytical thought and for the clear exposition of ideas and policy recommendations.[4] However, even Pearce’s capacities were put to the test by the heavy demands placed upon him as Minister for Defence during World War I. A Royal Commission that inquired into the administration of the defence department in 1917 returned a generally favourable verdict, but it found much to criticise, even allowing for the difficult and unprecedented circumstances confronting Pearce and the extraordinary burden he had been asked to carry. But, as Menzies also noted, Pearce was blessed with a ‘profound and reflective mind’, the prerequisite for drawing some profit from one’s mistakes.[5]

In 1916 the Australian labour movement split over the question of conscription. Pearce and the Prime Minister, W. M. Hughes, supported conscription. They, and several other government members, walked out of a meeting of the federal Labor Party on 14 November and formed a minority government. Soon after, they joined forces with their former political opponents, with the result that a weakened Labor Party remained out of office federally for twelve years. The labour movement never forgave its ‘rats’. For the rest of his political life Pearce was reviled as a class traitor and it was not difficult for his staunchest opponents to find evidence of a career marked by apostasies. The political tide had been running against Free Trade when Pearce entered the Commonwealth Parliament, and he had to abandon beliefs which he had defended vigorously in the 1890s and early 1900s. Similarly, he had opposed what he called militarism in 1901, but Russia’s defeat by Japan in 1905 convinced him of the need for compulsory military training. He was not alone in making these changes of direction, which, at the time, were understandable and not considered remarkable. But after the conscription split they were offered as further evidence that Pearce was a time-serving Vicar of Bray.

To his Labor critics, Pearce compounded his numerous sins when, as Leader of the Opposition in the Senate in the early 1930s, he played a leading role in obstructing the Scullin Government’s plans to combat the Great Depression. The Opposition senators, who outnumbered those of the Government four to one, allied themselves with those individuals and organisations in the community calling for conventional budgetary strategies and the full payment of overseas debts. Early in 1931 they rejected the legislation on which the Government’s recovery plan was to be built. Pearce did not determine the Opposition’s policy, but he executed it with skill and tenacity. His most newsworthy ploy was to call Sir Robert Gibson, Chairman of the Commonwealth Bank Board, and a well-known advocate of ‘classical’ belt-tightening measures, before the bar of the Senate.[6] Many economists since have argued that the deflationary policies forced upon the Government prolonged the Depression. The Government’s proposals, which might be characterised as implicitly Keynesian, could have led to a much quicker recovery. Pearce never accepted this argument and always believed that he had helped save Australia from disaster.[7] His action in calling Gibson before the Senate, however, along with the visit to Australia of the Bank of England’s Sir Otto Niemeyer, now underpins an Australian political tradition which holds that bankers and capitalists successfully conspired to save their own skins at the expense of the Australian working class.

The labour movement’s hatred of Pearce had no impact on his electoral prospects as he had successfully traded its support for that of Western Australia’s non-Labor voters. But many of them were wavering by the early 1930s. Increasingly from 1922 onwards, as Western Australia’s sole federal minister, Pearce was ‘held accountable for the evils, real and imaginary’, of Federation. There is ample testimony that he fought hard for his state. His parliamentary career began with his calling for the construction of a transcontinental railway line. Towards its close, he was instrumental in the Commonwealth Government’s decision to create the Commonwealth Grants Commission as a means of improving financial outcomes for the states, particularly the less populous ones. In between he had done much else. But he never paraded his loyalty in the manner of the more strident states’ rights champions. Thus he became vulnerable when he refused to support the Western Australian secession movement as it gathered momentum in 1932 and 1933. He was among a visiting group of Commonwealth parliamentarians who were jeered and abused when they tried to talk Western Australians out of voting to secede. And even though secession soon lost its appeal, the leading secessionist body, the Dominion League of Western Australia, continued to harry him. At the 1937 elections, parading all his sins of commission and omission, it ran a strong ‘Put Pearce Last’ campaign. The response from voters was sufficient to bring about Pearce’s defeat.

When the Commonwealth Parliament moved from Melbourne to Canberra in 1927 Pearce was the only remaining original senator. It was fitting, although the ALP may have wished otherwise, that he should have survived long enough to make the transfer. He never doubted that the Senate was a crucial component of Australian parliamentary democracy and his career did much to promote that view among the Australian public. It is fitting, also, that the first edition of J. R. Odgers’ Australian Senate Practice, published in 1953, carries a quote from the country’s longest serving senator immediately after the title page. ‘The Senate’, Pearce stated:

was constituted as it is after long fighting, prolonged discussion, many compromises and many concessions on the part of the various shades of political thought throughout the Commonwealth and it stands there in the Constitution in a position that has no equal in any Legislature throughout the world.

These are the sentiments of a true believer, but it is the insularity of the claim in the last two lines that strike the modern reader. It tells us much about Pearce’s world and about his values. In the second half of the twentieth century no Australian senator, regardless of the affection he or she felt for the Senate, could have ignored, or forgotten, the constitution of the USA.

Pearce made no attempt to re-enter Parliament, but other demands were soon made upon his talents. He served on the Commonwealth Grants Commission from 1939 to 1944 and was Chairman of the Defence Board of Business Administration from 1940 until it was disbanded in 1947. Of Pearce’s chairmanship of the board, Sir Paul Hasluck has written: ‘. . . he was a diligent, shrewd and unruffled administrator who knew the defence organisation, knew Cabinet, and knew the community and Australian industry, but had no axes to grind or favours to confer’.[8]

Moustached and with brown eyes, Pearce was relatively tall, standing just under six feet. He lived modestly, was a lifelong teetotaller and, being neither outgoing nor convivial, was regarded as serious-minded by his contemporaries. There seems little doubt that he became more conservative as he grew older. Joseph Lyons, Prime Minister during Pearce’s last years in Parliament, referred to him as ‘our Tory’.[9] Lyons may have been thinking of the deliberate, judicious Pearce who so appealed to Menzies. In another sense, though, the epithet was apt. During the 1920s and 1930s, Pearce criticised strikers and union leaders in terms that made it difficult for anyone to imagine that he had once been both.[10] But he had never been a radical. He began his parliamentary career wanting to ‘civilise’ capitalism in the interests of the underprivileged, who hoped for greater security and independence in their lives. While his speeches in the early 1900s were enough for some people to label him a socialist, he had no sympathy for the forms of socialism that developed in Australia in the early twentieth century. Indeed, most of the ideas that interested him had found legislative expression, at least in some measure, by 1913. Had he not then become preoccupied with defence matters, it is doubtful whether he would have had much more to contribute to Labor’s social policies.

On 23 April 1897, while still blacklisted by building trades employers, Pearce had married, in accordance with Congregational forms, Eliza Maud Barrett at Trinity Church, Perth, daughter of Richard Barrett, a French-polisher. She died on 16 February 1947. There were two sons of the marriage, Phillip and George, and two daughters, Dorothy and Marjorie. Pearce was sworn as a member of the Privy Council in 1921 and appointed an Officer of the Legion of Honour in 1924 and KCVO in 1927. He was not a regular churchgoer, although towards the end of his life he often attended Presbyterian services. After his election to the Senate, he lived mainly in Melbourne, a point not forgotten during the ‘Put Pearce Last’ campaign. But he did enjoy visits to a farm he owned with one of his sons in Tenterden, Western Australia. He died at his home in Elwood, Melbourne, on 24 June 1952, aged eighty-two, and was given a state funeral.[11]

The slight and anecdotal autobiography, Carpenter to Cabinet (1951), reveals little about Pearce himself and even less about his work as a parliamentarian and minister. Peter Heydon’s study, Quiet Decision (1965), is far better on both counts, although the focus is on Pearce after he had left the Labor Party. A portrait by Sir William Dargie hangs in Parliament House, Canberra.

[1] B. Beddie, ‘Pearce, Sir George Foster’, ADB, vol. 11; George Foster Pearce, Carpenter to Cabinet: Thirty-Seven Years of Parliament, Hutchinson & Co., London, 1951, pp. 13–19, 35; Peter Heydon, Quiet Decision: A Study of George Foster Pearce, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1965, pp. 15, 17; John Merritt, ‘George Foster Pearce and the Perth Building Trades Strike of 1897’, Labour History, Nov. 1962, pp. 5–22.

[2] Pearce, Carpenter to Cabinet, pp. 40–3; CPD, 15 Nov. 1901, p. 7357, 23 May 1901, pp. 255–62, 2 Sept. 1903, pp. 4460–2, 14 Dec. 1911, p. 4483, 20 Aug. 1903, p. 3913.

[3] CPD, 12 Nov. 1909, p. 5746, 6 Sept. 1911, pp. 84–97, 17 Dec. 1913, pp. 4578–87; Pearce, Carpenter to Cabinet, pp. 83–5, 96–9, 102–3, 118–19; Heydon, Quiet Decision, pp. 73, 133; John Merritt, ‘Pearce, Sir George Foster’, in E. T. Williams and Helen M. Palmer (eds), The Dictionary of National Biography, 1951–1960, OUP, London, 1971; CPD, 12 July 1922, pp. 298–312, 14 Mar. 1923, pp. 331–7, 22 June 1926, p. 3321, 15 May 1924, pp. 658–9, 10 Sept. 1924, pp. 4098–100, 21 Jan. 1926, pp. 228–40.

[4] CPD, 8 July 1926, p. 3945, 11 June 1926, pp. 2949–57, 22 July 1926, p. 4451; Argus (Melb.), 24 May 1927, p. 16; CPD, 3 Dec. 1935, pp. 2340–3; Heydon, Quiet Decision, pp. 1–4; Menzies wrote an introduction to Heydon’s biography entitled ‘Never Sat with an Abler Man’.

[5] CPP, Royal Commission on Defence Administration, reports, 1918, 1919; Heydon, Quiet Decision, p. 2.

[6] Ross McMullin, Light on the Hill: The Australian Labor Party 1891–1991, OUP, South Melbourne, 1991, pp. 102–9; Pearce, Carpenter to Cabinet, pp. 141, 189; Merritt, ‘Pearce, Sir George Foster’, p. 798; Heydon, Quiet Decision, pp. 2, 52; Geoffrey Sawer, Australian Federal Politics and Law 1929–1949: MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1963, pp. 15–16; CPD, 6 May 1931, pp. 1615–32.

[7] Beddie, ‘Pearce, George Foster’; Pearce, Carpenter to Cabinet, pp. 189-90.

[8] Merritt, ‘Pearce, Sir George Foster’, p. 798; Heydon, Quiet Decision, pp. 180, 184; CPD, 23 May 1901, p. 260, 7 Nov. 1907, p. 5684, 26 May 1933, pp. 1922–6; Paul Hasluck, The Government and the People 1939–1941, AWM, Canberra, 1952, p. 448.

[9] Heydon, Quiet Decision, p. 5; Merritt, ‘Pearce, Sir George Foster’, p. 798; Beddie, ‘Pearce, Sir George Foster’.

[10] CPD, 21 May 1931, pp. 2172–4.

[11] Heydon, Quiet Decision, p. 212; SMH, 25 June 1982, pp. 1, 2; CPD, 6 Aug. 1952, pp. 18–19; Age (Melb.), 25 June 1952, p. 2, 26 June 1952, p. 8; Argus (Melb.), 25 June 1952, pp. 1, 7, 26 June 1952, p. 11; The Times (Lond.), 25 June 1952, p. 18; Frank C. Roberts (comp.), Obituaries from The Times 1951–1960, Newspaper Archive Developments Limited, Reading, England, pp. 558–9.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 2, 1929-1962, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic., 2004, pp. 15-20.