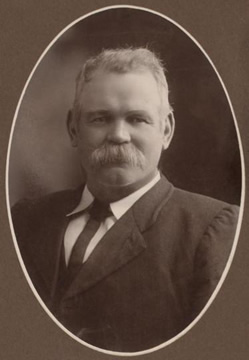

McGREGOR, Gregor (1848–1914)

Senator for South Australia, 1901–14 (Labor Party)

Gregor McGregor, stonemason, builder’s labourer, trade unionist and first Labor leader of the Senate, was described by a Senate colleague as having ‘a grim, pawky Scottish brand of humour with a certain bad boy flavour about it’.[1]McGregor was born on 18 March 1848, son of Malcolm McGregor, gardener, and his wife Jane, in Kilmun, Argyllshire, Scotland. Gregor spent his childhood in Scotland and County Tyrone, Northern Ireland, where he attended the local national school, though he seems to have been largely self-educated. Following his return to Britain in 1866, he worked as an itinerant agricultural labourer before finding employment at the Clyde shipyards in 1867. During the years 1869–76, he became an active trade unionist and was involved in successful protests aimed at reducing the working week for blue-collar workers.

In 1877, McGregor arrived in South Australia as an assisted migrant, on board the SS Mangalore. He took up work as an agricultural labourer in the mid-north of the colony. At some time, he worked for Sir Richard Baker. An accident left him with impaired vision, but it was thought that his disability, which he mocked with his keen Scots wit, served to improve an already good memory to the point at which it was described as ‘phenomenal’. On 30 April 1880, he married Julia Anna Steggall, who died within the year. Two years later, at the Baptist Church, Flinders Street, Adelaide, he married the widowed Sarah Ann Brock, née Ritchie, taking on the role of stepfather to her son. In 1894, Sarah appears to have been illiterate.

Unable to find employment in South Australia, in 1885 McGregor moved to Victoria to work as a stonemason. On his return to South Australia, he laboured as a navvy on the railways and on a variety of building projects. McGregor became increasingly active in the United Builders’ Labourers Society. From 1892, he was a member of the United Trades and Labor Council of South Australia, serving on the Council’s parliamentary committee (1892–1901), where he gained a reputation as an astute negotiator and a commanding public speaker. In 1894, McGregor, now a Justice of the Peace, was elected to the Legislative Council for the Southern District. Issues that engaged his attention in the Council included the extension of the franchise, land reform to reduce the hold of ‘monopolists’, and the extent of Chinese migration to Australia. He wassoon seen as one of South Australian Labor’s most effective politicians.[2]

In March 1901, he was elected to the Commonwealth Parliament as South Australia’s first Labor senator. Here, as in the Legislative Council, he became renowned for his cheeky and ready wit and his frequent use of biblical imagery. His first speech in the Senate was along much the same lines as the one he had given at a campaign meeting in the Hindmarsh Town Hall, though his argument against ‘coloured’ labour centred on his conviction that Chinese people worked harder than did Australians. Commenting that the more progressive the legislation, the better he liked it, he argued for the extension of the suffrage to all the women of the newly federated Australia. He wryly commented that while he was given a mandate to represent both genders from his home state ‘some are only representing the manhood of the people, and some even a kind of double‑breasted manhood’. He suggested that Labor would support whichever one of the other parties implemented Labor’s policies, and he challenged the first bidder:‘I as the representative of a party am waiting. We are for sale . . .’. In the elections of 1903 and 1910, he topped the South Australian Senate poll, leading his colleagues by some thousands of votes.[3]

Throughout his parliamentary career, McGregor championed the cause of the ‘workers’. He laboured for improved working conditions, workers’ compensation and the aged pension, as well as for the protection of Australian industry. He sometimes used his own experiences as a labourer to highlight the plight of workers who lived in grinding poverty. An ardent supporter of compulsory unionism, he advocated a minimum wage that would allow workers and their families to live with dignity. McGregor asserted that without resourceful trade unionists, able to negotiate on behalf of their members, workers would be left ‘to live on seaweed, on Indian meal, on potatoes, on anything one liked, from the beginning of the year to the end’.

McGregor sought to extend the role of the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration to encompass the employment conditions of agricultural workers. Elected to the Senate on protectionist policies, he caller for higher wages as well as higher tariffs. ‘I would like to point out’, he said in 1913, ‘that . . . the Labour party was pledged to a platform which set out that the only Protection we could support was the new Protection—Protection through the Customs House to the manufacturer, and protection to all the workers of Australia through the Conciliation and Arbitration Court’.

McGregor enthusiastically endorsed the White Australia policy as a means of eliminating ‘sweated’ labour. He was particularly critical of the Queensland sugar industry for employing Melanesian contract labourers at starvation rates in order to compete successfully against imported sugar. He suggested that Australian consumers should be prepared to pay a halfpenny more per pound for sugar than rely upon ‘sweated labour’.

Despite his long-standing membership of the Church of Scotland, McGregor was critical of the role that organised religion had sometimes played in pacifying the working class. Speaking from his own experience, McGregor stated with blunt candour: ‘. . . we were taught in the Sunday schools to order ourselves lowly and reverently before our betters . . . Those were the days when the worker was treated very little better than a pig’. He held there was no divine plan to ensure that one section of the community lived in luxury whilst another bordered on starvation.

A member of the Adelaide Democratic Club, he was disdainful of the trappings of power and objected to soldiers in the armed forces dressed in ‘cocked hats, feathers, and gold lace’. As a candidate for the 1903 Senate election, McGregor had protested against what he considered had been the extravagance of Lord Hopetoun, the previous Governor-General, and argued for the appointment of a local administrator and a ‘citizen soldiery’.[4]

In May 1901, the Labor Caucus elected McGregor to represent the Party in the Senate. In June 1905, he became vice-chairman of the Caucus, and in June 1906, party leader in the Senate, a position he would retain throughout his Senate career. For nearly fourteen years, during a formative period in federal politics, McGregor’s position at the helm of the Labor Party in the Senate testified not only to his popularity within the Party but also to his political competency. He was ‘a giant in debate’ and ‘fair and square in all his dealings . . . ’. An early Leader of the Government in the Senate, he was also the Senate’s second Leader of the Opposition. Earlier, McGregor had challenged those senators who were uncomfortable with the latter position because they considered that party divisions were inappropriate in a States House. Amongst these was the first Leader of the Opposition in the Senate, the Free Trader, Josiah Symon. ‘It appears to me’, ventured McGregor, ‘that all the Opposition are leaders . . . they are all suns . . .’.

As well as being leader of the Senate, during the two first federal Labor ministries (April–August 1904 and November 1908–June 1909), McGregor was also Vice-President of the Executive Council. He held these positions again when Labor first held power in its own right in 1910. At this time, he spoke of his satisfaction at being Senate leader from a position of strength. It was he said, so different from 1904 when he had found carrying on ‘the business of the Government’ very difficult. He thought it fortunate that the period then had been brief, but had no hesitation now ‘in taking up the work’ because he would be assisted by men in the Senate who had ‘both the ability and the inclination’, and who could be relied upon.

Nevertheless, the demands placed on McGregor were heavy. From 1910–13, the Parliament passed one hundred and thirteen acts. As Leader of the Government in the Senate, he had the responsibility of piloting the first substantial legislation of a federal Labor government through the Senate. He introduced most of the major bills. According to George Pearce, McGregor, ‘when preparing himself for a debate in the Senate’, would have extensive ‘figures and facts’ read to him once or twice, after which he could ‘repeat them accurately’. He would then rise and reply to an opponent ‘by dissecting the figures used and demonstrate that the conclusions arrived at by the former speaker were wrong’. A splendid example of this can be found in the staggering array of statistics used by McGregor when introducing the Land Tax Bill in 1910.[5]

During his time in the Senate, McGregor also served on two royal commissions including that on the Commonwealth tariff. He had taken an early interest in the development of Standing Orders when his reservations regarding the numbers required for an adjournment debate were supported by Senator Symon; he later became a member of the standing orders committee. His Senate committee service also included chairmanship of the select committee inquiring into a construction contract on the transcontinental railway. McGregor pressed (unsuccessfully) for the government department in question to supply information and documentation relevant to the inquiry.

Following the return of the Liberals to government in 1913, there were twenty-nine senators on the Labor side to seven on the government benches. By now, McGregor had earned himself the reputation of being a great Senate ‘tactician’. He was resoundingly re-elected as vice-chairman of the Caucus, and thereby Leader of the Opposition in what was for the Cook Government an exceedingly ‘hostile’ Senate, one whose activities heralded the Commonwealth’s first double dissolution. On 17 June 1914, McGregor moved the Address to the Governor-General that requested the publication of the Cook Government’s reasons for calling the double dissolution. On 30 July 1914, the Parliament wasdissolved. The election was due on 5 September.[6]

Gregor McGregor died on 13 August 1914, between the day of his nomination and the day of polling. As a man who had always ridiculed pomposity, it was ironic that he was honoured with a state funeral. He was buried at West Terrace Cemetery, Adelaide, and was survived by his wife and stepson.Crawford Vaughan, later premier of South Australia, stated that Gregor McGregor ‘came from the masses, and labored for the masses’. The Bulletin wrote of him as ‘the Labor leader for whom the Senate had a genuine affection’, commenting that despite his having been almost blind for over twenty years, he had remained ‘one of the best informed members of the [Labor] party’. In the Senate, George Pearce said that ‘very few men make so many friends’. Senator Edward Millen referred to McGregor’s career as ‘a record of great and useful achievements, attained by determination and courage in the face of difficulties that would have broken a less valiant heart and crushed a less resolute spirit’.

For a political eulogy, the Adelaide Advertiser’s was hard to beat: ‘Men of the late Mr. McGregor’s robust and patriotic type do honor to the State and Commonwealth, and the loss of their public services is more than a party misfortune; it makes the nation poorer’.[7]

[1] George Foster Pearce, Carpenter to Cabinet: Thirty-Seven Years of Parliament, Hutchinson & Co., London, 1951, p. 49.

[2] H. T. Burgess (ed.), The Cyclopedia of South Australia, vol. 1, 1907, Cyclopedia Company, Adelaide, p. 177; CPD, 10 September 1913, pp. 1016–1017; G. C. Grainger, ‘McGregor, Gregor’, ADB, vol. 7; Advertiser (Adelaide), 14 August 1914, p. 8; SMH, 14 August 1914, p. 6; Advertiser (Adelaide), 19 May 1894, p. 4; Minutes of the United Trades and Labor Council of South Australia, 1891–1901, Butlin Archives, ANU; Ross McMullin, The Light on the Hill: The Australian Labor Party 1891–1991, OUP, South Melbourne, Vic., 1991, pp. 30–31; SAPD, 18 August 1914, pp. 262-263, 11 August 1896, pp. 134 -136, 1 July 1896, p. 39-45.

[3] Advertiser (Adelaide), 26 February 1901, p. 6; CPD, 22 May 1901, pp. 130–143.

[4] CPD, 5 February 1902, p. 9663, 10 September 1913, pp. 1009-1020; Advertiser (Adelaide), 10 December 1903, p. 8.

[5] Geoffrey Sawer, Australian Federal Politics and Law 1901–1929, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1956, p. 19; SAPD, 18 August 1914, p. 262; CPD, 22 May 1901, p. 131; Patrick Weller (ed.), Caucus Minutes 1901–1949: Minutes of the Meetings of the Federal Parliamentary Labor Party, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1975, vol. 1, pp. 44, 156, 172, 188, 215, 279, 322, 349; CPD, 6 July 1910, p. 67; Sawer, Australian Federal Politics and Law, p. 91; Pearce, Carpenter to Cabinet, p. 49; CPD, 3 November 1910, pp. 5560–5561.

[6] CPP, Report of the royal commission on the transport of troops returning from service in South Africa, 1902, CPP, Reports of the royal commission on the Commonwealth tariff, 1905–07; CPP, Special report of the select committee on Mr Teesdale Smith’s contract—Kalgoolie to Port Augusta railway, 1914; Punch (Melbourne), 14 December 1911, p. 956; Weller, Caucus Minutes, p. 320; CPD, 17 June 1914, pp. 2169–2184.

[7] Advertiser (Adelaide), 14 August 1914, p. 8; Bulletin (Sydney), 20 August 1914, p. 7; CPD, 8 October 1914, pp. 11-12.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 153-157.