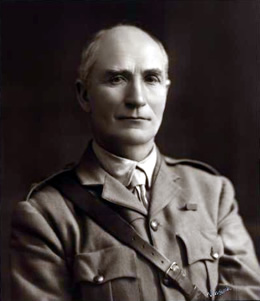

O’LOGHLIN, James Vincent (1852–1925)

Senator for South Australia, 1907, 1913–20, 1923–25 (Australian Labor Party)

James Vincent O’Loghlin, the only senator to be on active service in World War I, was born at Gumeracha, in the Adelaide Hills, on 25 November 1852, the son of James O’Loghlin and his wife Susan, née Kennedy. His father, who was a farmer, had emigrated to South Australia from County Clare, Ireland, in 1840.

O’Loghlin spent the first half of his life in the mid-north and lower-north of South Australia. He was educated at Besley’s Catholic School in Kapunda and at the Kapunda Classical and Commercial Academy. After working on farms and stations, he joined the South Australian Carrying Company in 1873, becoming its manager at Gawler. He was later employed by the Gawler millers, W. Duffield and Company, as a wheat buyer. When the firm amalgamated with the Adelaide Milling and Mercantile Company, O’Loghlin was sent as its manager to Terowie and was later transferred to Gladstone. While living in Terowie (1883–87), he began to take an interest in public affairs. He was on the committee of the Terowie Institute and founded and edited the Terowie Enterprise and North-Eastern Advertiser. At some point in his career he became president of the South Australian Shorthand Writers’ Association.[1]

Throughout his life, O’Loghlin showed a marked capacity for multiple loyalties. He was proud of his family’s Irish background and was a strong supporter of Irish home rule. He was one of six South Australian delegates who attended the Irish–Australian Convention in Melbourne in November 1883 and heard the message of support from C. S. Parnell read by the visiting Irish Nationalists, John and William Redmond. He often wrote and spoke on Irish politics and at various times he was president of the South Australian branches of the Irish National League, the Self-Determination for Ireland League and the United Irish League. In November 1919, he attended the Australasian Irish National Convention summoned by Archbishop Mannix and two years later he sent a message of congratulations to Eamon de Valera on the establishment of the Irish Free State. O’Loghlin’s Irish nationalism was moderate and was paralleled by a strong sense of Australian patriotism and also devotion to the British Empire. He was an active member of the Australian Natives’ Association and his admiration of British political leaders, such as David Lloyd George, was unaffected by the traumas of World War I.[2]

Another lifelong interest was military service. O’Loghlin joined the Terowie Volunteer Corps in 1883 and for twenty years he never missed an annual training camp. In 1895, he was appointed a captain in the South Australian Militia and in 1904 he was promoted to the rank of major in the 10th Australian Infantry Regiment. For some years, he commanded an Irish Corps and later in the Senate he was to defend the formation of Irish and Scottish military units. He excelled in the use of the rifle, winning awards and leading the South Australian Parliamentary Rifle Team. In November 1909, he retired from the Commonwealth Military Forces with the honorary rank of lieutenant colonel.[3]

In May 1888, O’Loghlin was elected to the South Australian Legislative Council as one of the four members representing the Northern District. It was a vast electorate, covering the greater part of the colony, including the Northern Territory. He was not associated with any faction, but was soon recognised as one of the few liberals in the upper House. In 1891, the Quiz and the Lantern declared in an open letter: ‘you have demonstrated yourself to be a true Radical in what is in the main a highly Conservative Chamber . . . despite the unpopularity of your views . . . you apparently command their undivided respect . . . shown by your selection to serve on various Select Committees and Royal Commissions’. One of these was the 1890 royal commission on railway communication with Queensland. In March 1894, O’Loghlin was appointed a trustee of the Savings Bank of South Australia. Two months later, he was re-elected to the Legislative Council, heading the poll for the Northern District.[4]

On his election to Parliament, O’Loghlin had moved from Terowie to Adelaide. After several years, he built a house in the southern suburb of Hawthorn, where he lived for the rest of his life. He was a Justice of the Peace and, in 1889, founded the Catholic weekly newspaper, the Southern Cross. He was its editor for six years and continued to be managing director and secretary until his death. His successor as editor, W. J. Denny, described O’Loghlin as ‘a capable journalist . . . [with] a racy pen . . . and an excellent memory’. Under O’Loghlin’s control, the Southern Cross showed some sympathy for the infant Labor Party and for the politics of reform generally.[5]

In 1896, the position of chief secretary in the Ministry led by C. C. Kingston fell vacant. O’Loghlin was not Kingston’s first choice, but after a delay of five weeks he was offered the post and took up office on 18 March 1896. In later years, he frequently alluded to his experiences as Kingston’s lieutenant. As the only minister in the Council, O’Loghlin was responsible for steering through a wide range of legislation, including the 1896 Pastoral Bill, the 1896 Coloured Immigration Restriction Bill, the 1898 Public Health Bill, the 1898 Public Service Bill and the 1899 Federation Enabling Bill. Colonial defences came within his portfolio and he organised the first two South Australian contingents sent to South Africa in 1899. He served on the 1897 royal commission on government wharves and chaired the commission on the public service which was appointed in 1899.

Reform of the Legislative Council was the greatest challenge faced by Kingston and his Cabinet. In 1896 and 1898–99, O’Loghlin failed to persuade his colleagues in the Council to extend the franchise. The Governor refused to grant a double dissolution on the issue and on 1 December 1899 the Ministry resigned. O’Loghlin never held office again. In May 1902, he lost his seat, coming last in the Northern District poll. He declared it to be ‘a temporary banishment’. To some extent this was true, but in the next twenty years he was to experience an unusual number of electoral defeats.[6]

In the first federal elections in March 1901, O’Loghlin was one of eleven South Australian parliamentarians who stood for the Senate. He finished eighth. He had resumed his position with the Southern Cross, and in 1903 he was appointed by the South Australian Government as an honorary commissioner to inquire into the agricultural and dairying industries in New Zealand. He subsequently wrote a series of articles about New Zealand politics, government and industrial relations. He also wrote occasional tributes to political colleagues, such as Kingston and Frederick Holder, and the New Zealand Premier, Richard Seddon. On 23 January 1907, at the age of fifty-four, he married Blanche Besley, the daughter of his old schoolmaster.

O’Loghlin had often been described as a radical or liberal, but essentially he had been a ministerialist. He remained an admirer of Kingston, but whereas other former associates formed the Liberal Union, he joined the Labor Party in 1906. In June 1907, the Party held a plebiscite to select parliamentary candidates and O’Loghlin was one of the twenty elected from the ninety-four nominees. Within a few weeks, he was elected to fill a casual vacancy in the Senate by a joint sitting of the Houses of the South Australian Parliament. The vacancy had arisen when the High Court, sitting as the Court of Disputed Returns, had declared that the election of Joseph Vardon in 1906 had been invalid on account of ballot papers unjustifiably rejected by returning officers.[7]

O’Loghlin was sworn in as a senator on 17 July 1907 and in the next four months took part in a number of debates. His position, however, was invidious, as Vardon petitioned first the High Court and then the Senate, arguing that there should have been a new poll. The Senate committee of disputed returns and qualifications upheld Vardon’s petition, and the Senate ultimately referred the matter back to the High Court, which declared O’Loghlin’s appointment void. A new election was held in February 1908. Despite receiving campaign support from a number of federal ministers, O’Loghlin was defeated by Vardon. There were suggestions that he had not received the full support of the Labor Party; it was easy for the press to portray him as ‘an eleventh hour convert’ who lacked any connections with the trade unions.[8]

In April 1910, O’Loghlin was elected to the South Australian House of Assembly for the seat of Flinders. Despite his long parliamentary and ministerial experience, O’Loghlin did not obtain a portfolio in John Verran’s first Labor Ministry. At the February 1912 election, he was one of several Labor members who lost their seats.

At the federal election on 31 May 1913, O’Loghlin was elected one of the senators for South Australia, joining the huge Labor majority in the Senate. He was re-elected in September 1914, following the double dissolution. After July 1917, he was one of the small Labor minority in the Senate and, like all but one of his colleagues, was defeated in the 1919 election. Re-elected on 16 December 1922, he returned to the Senate in July 1923 and remained a senator until his death. In his nine years as a senator, O’Loghlin served on a number of committees, including the federal parliamentary recruiting committee, which existed for a fairly brief period in 1917–18.

In August 1915, at the age of sixty-two, O’Loghlin became the only senator to enlist for overseas service. He told George Pearce, that if ‘you cannot put me in the firing line, put me as near to it as you can’. Appointed a temporary lieutenant colonel, he commanded reinforcements on troopships which disembarked in Egypt in September 1915 and April 1916. On each occasion, his stay in Egypt was brief and he was disappointed not to be able to visit Gallipoli. In September 1916, while the conscription referendum campaign was taking place in Australia, he was on a troopship en route to Europe. He stayed in England for a few weeks. On the voyage home, he visited South Africa and made speeches about the war and Australian politics.[9]

In his absence, the political situation had changed drastically. At a Caucus meeting in August 1915, W. M. Hughes ‘made a feeling and eulogistic reference to comrade O’Loughlin [sic]’, wishing him ‘on behalf of the party God speed and a safe return’. By the time O’Loghlin returned to Australia in March 1917, many of his friends had followed Hughes and left the Labor Party. Knowing his commitment to the war effort, some of his colleagues had taken it for granted that O’Loghlin was a conscriptionist. However, in his first speech on returning to the Senate he insisted that he had declared his opposition to conscription as early as August 1916. At the same time, he was appalled by the split in the Party. He criticised the South Australian branch for expelling the conscriptionists, and refused to campaign against his old colleagues at the 1917 election. His somewhat equivocal position led to taunts and criticism for well over a year. Nationalist Senators spoke of his ‘masterly silence’ over conscription, while more militant Labor colleagues tried to provoke him to attack old friends. O’Loghlin’s support for the war remained unqualified, but by November 1918 he spoke harshly of the harm that Hughes had done to Australia and condemned the efforts of the Government to gain control of the former German colonies in the Pacific.[10]

Despite such occasional outbursts, O’Loghlin was generally a mild-mannered man, who was liked by most other senators. He was not an eloquent or combative speaker and his speeches in the Senate were seldom well-constructed or persuasive. Throughout his years in the Senate, he spoke regularly and confidently on defence matters and in one of his last speeches he argued that Australia should be self-reliant and should manufacture aircraft and submarines. Reflecting his rural background, he took a strong interest in agricultural problems and in the development of country towns. He had been a keen supporter of the trans-continental railway and he continued to call for the completion of the rail link between South Australia and Darwin. In his last years, he favoured an extension of Commonwealth powers and opposed attempts to curtail the operations of the Commonwealth Bank. He was critical of infringements of civil liberties by the Commonwealth Government and in 1917–18 raised a number of cases involving individuals imprisoned or interned under the War Precautions Act.[11]

By 1923, O’Loghlin was seventy and one of the oldest senators. He referred to himself ‘as a veteran, growing perhaps a little weary of the political battle’. To the concern of his colleagues, he continued to travel to Melbourne during the cold winter, but he seldom spoke in the Senate. In August 1925, he was granted two months leave. He died in Adelaide on 4 December and was buried in the West Terrace Cemetery. His wife, three sons and a daughter, survived him.[12]

[1] Peter Travers, ‘O’Loghlin, James Vincent’, ADB, vol. 11; Adelaide Observer, 18 January 1890, p. 33; O’Loghlin Papers, MS 4520, NLA.

[2] Advocate (Melbourne), 17 November 1883, pp. 5–10; Daily Herald (Adelaide), 9 December 1921, p. 5 ; Advertiser (Adelaide), 5 December 1925, p. 16; O’Loghlin Papers.

[3] CPD, 25 November 1914, p. 974, 17 December 1913, pp. 4592–4593, 29 May 1914, pp. 1678–1680.

[4] Quiz and the Lantern (Adelaide), 4 December 1891, p. 3.

[5] O’Loghlin Papers; Advertiser (Adelaide), 5 December 1925, p. 16; D. J. Murphy (ed.), Labor in Politics: the State Labor Parties in Australia 1880–1920, UQP, St Lucia, Qld, 1975, p. 247.

[6] Dean Jaensch (ed.), The Flinders History of South Australia: Political History, Wakefield Press, Netley, SA, 1986, vol. 2, p. 188; Advertiser (Adelaide), 19 May 1902, p. 5.

[7] P. Loveday, A. W. Martin & R. S. Parker (eds), The Emergence of the Australian Party System, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1977, pp. 249–297.

[8] Kadina and Wallaroo Times (Kadina), 15 February 1908, p. 2.

[9] Argus (Melbourne), 22 June 1917, p. 8; CPD, 13 January 1926, p. 11; O’Loghlin Papers, op. cit.; CPD, 14 March 1917, p. 11367; J. V. O’Loghlin, Personal dossier, B2455, NAA; Information received from Graham O’Loghlin, Canberra, 28 April 1998.

[10] Patrick Weller (ed.), Caucus Minutes 1901–1949: Minutes of the Meetings of the Federal Parliamentary Labor Party, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1975, p. 421; CPD, 14 March 1917, pp. 11360–11364, 14 November 1918, pp. 7795–7797.

[11] CPD, 13 August 1924, p. 3045, 29 April 1915, p. 2710, 2 August 1923, pp. 2002–2003, 24 July 1924, pp. 2406–2410, 14 June 1918, pp. 6029–6030, 25 September 1918, pp. 6299–6300, 19 September 1918, p. 6243, 16 October 1918, p. 6914, 15 November 1918, pp. 7892, 7919, 21 November 1918, p. 8164.

[12] Advertiser (Adelaide), 13 January 1923, p. 16; CPD, 13 January 1926, p. 11.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 183-187.