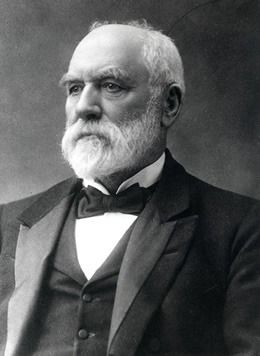

FERGUSON, John (1830–1906)

Senator for Queensland, 1901–03 (Free Trade)

John Ferguson, builder, contractor and mining investor, was born at Kenmore, Perthshire, Scotland on 15 March 1830, son of John Ferguson, weaver, and his wife Janet, née Ferguson. After a short period of primary schooling, he worked on the Marquis of Breadalbane’s estate. In 1847, he became a carpenter’s apprentice at Killin, later moving to Glasgow where he was employed as a journeyman and then as a carpenter. In 1855, he arrived in Sydney where, following unsuccessful attempts at prospecting on the Mudgee and Mount Ararat goldfields, he worked again as a carpenter. After an interlude in Sydney, he moved to Rockhampton in 1861. Ferguson then established a successful construction enterprise, which was responsible for many public and private buildings in Rockhampton and Central Queensland. In the mid–1880s he bought a tenth share in the Mount Morgan gold mine for £26 000. Subsequently, one third of Ferguson’s share was sold for £13 500. By 1888, he was able to retire, and from then on he spent extended periods overseas.

Ferguson was a municipal councillor from 1878 to 1890, and mayor of Rockhampton (1880–81) and (1882–83). He was Member for Rockhampton in the Queensland Legislative Assembly (1881–88) and sat in the Legislative Council between 1894 and 1906. His political thinking was influenced by Central Queensland’s need for roads, bridges, railways and cheap labour.

Ferguson was a strong supporter of the separation of Central Queensland from Brisbane, and of Federation. These causes ultimately proved to be incompatible. As section 123 of the Constitution would make clear, the onus for territorial separation was placed firmly on the legislatures of the states. Given the reluctance of southern Queenslanders to countenance such devolution and the fear of Labor control of the proposed two new Queensland states, Ferguson’s stance, even by 1899, was anachronistic. He had been, as ‘Honest John’, president of the Central Queensland Separation League, and had, during a visit to England between 1892 and 1893, presented the League’s case to the colonial secretary, Lord Ripon. A combination of imperial pressure and Brisbane intransigence scuttled the plan, although not before Ferguson had built one of the grandest private houses in Queensland, ‘Kenmore’, and had ordered monogrammed china and gold plate for what was to be Central Queensland’s future Government House.

Ferguson was out of Australia visiting Great Britain (and probably Japan) during the whole of the campaign to elect the first Federal Parliament. In his absence, he was selected as a Queensland candidate for the Senate on a platform embracing free trade and White Australia. Elected to the first Federal Parliament, he later told the Senate that he was ‘rather surprised’ to find that he was ‘one of the six chosen’.[1]

Ferguson, over seventy years old, in poor health and living in Sydney, contributed to three major debates during his term in the Senate. On 3 October 1901, he opposed an amendment to the Post and Telegraph Bill prohibiting the employment of coloured stokers on mail steamers in favour of white men. He believed that ‘no white man should be asked to work in the stoke-hole of a steamer in the Red Sea’, adding that it was ‘work for which the coloured men are specially adapted’. Another concern also surfaced: ‘I would ten times sooner travel in a steamer manned by lascars, who are our own loyal subjects, than with a steamer manned by a crew of mixed foreigners’. Ferguson considered the proposal as disloyal to the British Empire, of which he counted himself ‘a strong supporter’.[2]

On 14 November 1901, Ferguson expanded on his ‘White Australia’ philosophy during the second reading of that cornerstone of a white Anglo-Celtic Australian settler society, the Immigration Restriction Bill. He stated that this was ‘the most important measure that we have yet had before us’. He did not ‘believe altogether in the Bill [and did] not like it’. As an imperialist, he agreed with the British Colonial Secretary, Joseph Chamberlain, that there should be no distinction in the British Empire between man and man on the basis of colour. Australia was not in a position to stand alone in the world by adopting exclusivist racial policies. Not only were the Japanese ‘a proud and civilised people’, but Indians should be regarded equally as citizens of the Empire. Ferguson saw New Guinea, as a territory of the Commonwealth, as a source of cheap labour which could replace Melanesian workers. He also believed, contrary to most conventional opinion, that when Aborigines are ‘well fed and taken care of they develop into good workers’. How, he argued, could their position be reconciled with the White Australia policy, which ‘has become a ridiculous cry, and nothing else’.[3]

Ferguson’s strongest disagreement with the policies of the new Commonwealth was in relation to the Pacific Island Labourers Bill, which had as its objective the deportation of all Melanesian indentured labourers (Kanakas) by 1906. Mistakenly predicting the ‘utter ruination’ of the sugar industry if the Kanakas were too hastily expelled, Ferguson supported Senator Walker’s amendment aimed at allowing Kanakas who had been in Queensland for more than five years to remain permanently. After Walker’s amendment was lost by fifteen votes to ten, Ferguson moved his own amendment to exclude that part of Australia north of the Tropic of Capricorn from the Bill’s jurisdiction. This was defeated by sixteen votes to ten. During the debate, Ferguson reiterated his view that while he agreed that ‘the kanaka must go’ he was in favour of an extension of the repatriation period. Not one among the other five Queensland senators supported either Ferguson’s or Walker’s amendments, leading Ferguson to remark that the ‘greatest enemies of Queensland are her own representatives’.[4]

By now, Ferguson was seriously ill; he made only three further speeches, all brief and of no great moment. His attendance in the Senate was less than constant; he was absent for 128 of the 222 sitting days in the first and second sessions of the Parliament. Ferguson was absent without leave for two consecutive months, and as a result his seat was declared vacant on 13 October 1903, the only time that this has occurred in the history of the Commonwealth Parliament. As he had continued to hold his Legislative Council seat in the Queensland Parliament, the Commonwealth Electoral Act of 1902 would, in any case, have prevented his renomination (Queensland was the only state not to legislate to prevent sitting MPs from simultaneously occupying seats in the federal and state parliaments). As a public speaker, Ferguson was described as ‘clear and plain, but no more. He had not a touch of the orator. In debate . . . he lacked fire’.[5]

Ferguson died at his mansion ‘Winslow’, Darling Point, Sydney, on Friday 30 March 1906. On 1 March 1862, he had married Eliza Frances Wiley in Sydney, who, with one son, John, and five daughters, Elizabeth, Catherine, Mary, Janet and Helen, survived him. (Catherine had married the Hon. J. T. Bell, a Queensland cabinet minister and a speaker of the Queensland Legislative Assembly). Two other daughters had predeceased him. Ferguson, who left a Queensland estate probated at £218 319 and another probated at £12 179 in New South Wales, was buried in Waverley Cemetery with rites befitting a deacon of the Congregational Church.

A Gaelic speaker who did not learn English until a young man, Ferguson’s political contribution was mainly devoted to the economic development of Rockhampton and Central Queensland. Nevertheless, this honest and unassuming Scots–Australian did, through his brief appearance in the Senate, debate minority positions which, while somewhat contradictory and unfashionable, revealed astute insights into seminal questions of race, imperial relations and economic development.[6]

[1] David Carment, ‘Ferguson, John’, ADB, vol. 8; CPD, 29 May 1901, pp. 362–366; V. R. de Voss, Separatist Movements in Central Queensland in the Nineteenth Century, BA (Hons) thesis, University of Queensland, 1952.

[2] CPD, 3 October 1901, pp. 5544–5545.

[3] CPD, 14 November 1901, pp. 7281–7283.

[4] CPD, 21 November 1901, pp. 7561, 7590–7599, 29 November 1901, pp. 8015–8016; Senate, Journals, 29 November 1901, 4 December 1901; CPD, 29 November 1901, p. 8024, 5 December 1901, p. 8300.

[5] CPD, 13 October 1903, p. 6000; Gavin Souter, Acts of Parliament, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1988, p. 78; CPD, 18 June 1903, pp. 1099–1100; Capricornian (Rockhampton), 7 April 1906, p. 43.

[6] Capricornian (Rockhampton), 7 April 1906, p. 43; Queenslander (Brisbane), 7 April 1906, p. 29.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 89-92.