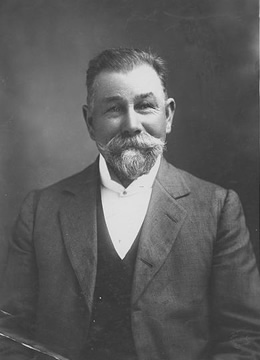

BARKER, Stephen (1846–1924)

Senator for Victoria, 1910–20, 1923–24 (Australian Labor Party)

‘It was’, wrote the Bulletin at the time of Stephen Barker’s death, ‘the dream of his life to get into the Senate’. Barker, tailor and trade unionist, was born in 1846, in London, England, son of Stephen Barker, farmer, and his wife Hannah, née Nagle. It is likely the whole family migrated to Australia. From the age of twelve, Barker worked in Melbourne as a presser for several clothing manufacturing houses, including Sargood, Son & Co. and Sahlberg & Son. After a spell in Tasmania and New Zealand, he returned to Melbourne, working for Beath, Schiess & Co. and then Barthold & Co. In the 1890s, he was engaged in North Melbourne as a tailor and dyer. In 1893, he gave evidence to the Factories Act Inquiry Board against ‘sweating’. Many years later he would recall what it had been like not to be able to ‘jingle one shilling upon another’.[1]

Barker was strongly committed to the trade union movement. He was actively involved in the Pressers’ Society (later Union), and a foundation member of the Tailors’ Union and the Victorian Clothing Operatives’ Union. For many years, he was associated with the Trades Hall Council (THC). He served as a member of the THC’s Eight-Hours committee in 1896–98, working ‘about 96 hours a week’. President of the THC from 1897–98, in 1901 Barker was elected permanent secretary in succession to J. G. Barrett, holding this position until 1910. One of his most remarkable achievements, as president and then treasurer of the THC organising committee, was the establishment in 1900–02 of wages boards for some sixty unions. He was a member of the first clothing trade wages board, and represented the clothing trade on the THC from 1892–1907. He was also a delegate to the THC for various other unions, including the Musicians’ Union of which he was an honorary member. He was one of the guiding forces in the establishment of Victoria’s first Tramway Employees’ Association. As a trade union official, Barker displayed practical common sense and excellent organisational skills, his name, according to Labor Call, being ‘imperishably enrolled on the walls of the Trades Hall’. Methodical and systematic in his approach, he administered the THC capably, nurturing it to maturity. Barker served as a local councillor for North Melbourne from 1901to 1905, and briefly as mayor in 1905.[2]

In 1899, he contested a by-election for the seat of Melbourne North in the Victorian Legislative Assembly as a Labor candidate. Unsuccessful, he turned to the new arena of federal politics. He ran unsuccessfully for the Senate in 1901, 1903 and 1906, finally winning in 1910. In 1901, Barker had been closely involved in the formation of the Political Labor Council.[3]

Barker was a man of independent mind who acted according to his principles and empathised with working-class people: ‘I am of them, I come from them, and I owe my political life to them’. His contribution to debate was somewhat modest in quantity and, for the most part, in tone; his voice was described as having the ring of ‘inexhaustible good nature’. Supporting the Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Bill in 1910, he spoke for ‘peaceful settlement’ of industrial disputes.

A believer in ‘the new Protection pure and simple’, he argued against increased protection for paper mills until employees were given ‘better treatment’. On the Commercial Activities Bill in 1919, he referred to having been in the cloth manufacturing trade ‘for thirty or forty years’. There is, he affirmed, ‘no better woollen material in the world than that manufactured from our Australian wool’. His argument was supported by his inspection of tweeds presented by Senator Pratten. In 1911, he objected to postal voting, citing instances of corruption observed in his nineteen years as a magistrate. He could argue cogently, if a little repetitively, as in the early hours of 16 September 1910, when he spoke against Yass–Canberra as the site of the national capital.

At times he was forceful. Referring to the Government Preference Prohibition Bill, he said it was ‘a mere sham and a pretence’ and an ‘insidious’ attack on unionism. He opposed the proposal to pay Sir Samuel Griffith a pension on his retirement as Chief Justice of the High Court: ‘It is a strange world we live in, and one of the strangest things in it is that it is the fat pig that gets the most grease’.[4]

Barker visited England at the invitation of the Empire Parliamentary Association in 1916, and in the same year was a member of the Australian parliamentary delegation to the Western Front. He lost his seat at the 1919 federal election. In 1922, he tenaciously sought re-election and found himself at the top of the poll for Senators from Victoria. However, from then until his death in office, he seldom engaged in debate.

Barker died, after a long illness, on 21 June 1924 at Statenboro private hospital, Toorak, and was buried in Brighton Cemetery. On 6 April 1874, he had married English-born Jane Laughton at St Paul’s Church of England, La Trobe Street, Melbourne. They settled in Elizabeth Street, Richmond, and were to have seven children. Jane predeceased him, but five of his children—John, Amelia, Sadie, Reginald and Albert—survived him.

A Justice of the Peace, Barker had favoured the temperance movement and was a long-time council member of the Working Men’s College. He was a supporter of womanhood suffrage, described by Tocsin in 1899 as having, at a meeting in Trades Hall, ‘feelingly referred to the excellent work’ of the Australian feminist, Henrietta Dugdale. In August 1900, at a meeting of the Trades Hall Council, Barker moved that a resolution be placed before the Victorian Parliament requesting that the Federal Electoral Bill not become law until the Legislative Council desisted from placing a veto on the extension of the Victorian franchise to women. Not surprisingly, Vida Goldstein supported Barker’s proposal.

A ‘great reader’, Barker was happy in the library of his East St Kilda home, surrounded by his extensive collection of books, curios and pictures. On weekends, he often wandered down to Yarra Bank to listen to the soapbox orators. This may have reminded him of occasions such as that in May 1897 when, as a member of the Melbourne May Day Committee, he spoke on behalf of International Labor Day. His summers were spent at his weatherboard residence at Carrum.[5]

[1] Bulletin (Sydney), 26 June 1924, p. 20; ‘Barker, Stephen’, ADB, vol. 7; VPP, Factories Act Inquiry Board—minutes of evidence, 1895; CPD, 20 December 1918, p. 9902.

[2] Tocsin (Melbourne), 29 March 1906, p. 2, 20 April 1899, pp. 4–8; Bulletin (Sydney), 26 June 1924, p. 20; Argus (Melbourne), 23 June 1924, p. 12; Punch (Melbourne), 21 July 1910, p. 80;Labor Call (Melbourne), 26 June 1924, p. 7; Argus (Melbourne), 31 October 1905, p. 5

[3] Table Talk (Melbourne), 29 March 1906, p. 13; Tocsin (Melbourne), 29 March 1906, p. 2; Punch (Melbourne), 21 July 1910, p. 80; Tocsin (Melbourne), 25 October 1906, p. 5; Trades Hall Council minutes, E/138/7, Butlin Archives, ANU.

[4] CPD, 20 December 1918, p. 9902, 19 August 1910, p. 1808; Punch (Melbourne), 21 July 1910, p. 80; CPD, 23 November 1910, p. 6574, 27 August 1919, pp. 11944–11945, 1 November 1911, pp. 2036–2037, 15 September 1910, pp. 3204–3206, 10 December 1913, pp. 4034–4036, 20 December 1918, pp. 9900–9902.

[5] Tocsin (Melbourne), 12 October 1899, p. 7; Labor Call (Melbourne), 26 June 1924, p. 7; Argus (Melbourne), 23 June 1924, p. 12; CPD, 25 June 1924, pp. 3–6.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 308-310.