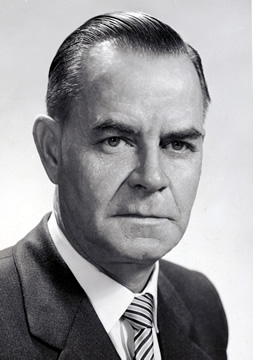

RIDLEY, Clement Frank (1909–1988)

Senator for South Australia, 1959–71 (Australian Labor Party)

While Clem Ridley was respected in the Senate for his knowledge of industrial affairs, his thoughtful contributions to debate, and his dignified bearing, his most significant achievements lay outside the parliamentary arena, as a dedicated and successful union leader, and as a steadying influence within the inner circles of the South Australian ALP during the time of the Split.

Clem Ridley was born Frank Clement Rhys Williams in Kalgoorlie, Western Australia, on 13 March 1909, the second child of Beatrice Ridley and Evan Williams. The Ridley family came from South Australia and Evan Williams, a grocer, was born in Victoria. After the disappearance of Evan (there is no apparent record of his death), Beatrice and her children lived in Perth with her relation, Victor Ridley. The Williams children adopted the name Ridley—thus Frank Clement Rhys Williams became Clement Frank Ridley.

When Clem was in his early teens the family moved to Adelaide, where he may have undertaken some technical education before becoming a fitter and turner in the General Motors-Holden’s Ltd (GMH) plant at Woodville. It was around this time that Clem and his older brother, Colin, joined the Glenelg branch of the ALP in South Australia. Clem was a member of the Vehicle Builders Employees’ Federation of Australia (VBEF) from the time of its establishment in 1938. From 1950 to 1959 he was general secretary of the VBEF, and from 1957 to 1959 its federal president and a member of the interstate executive of the ACTU. He was also president (1955–56) of the United Trades and Labor Council (UTLC) of South Australia, and a member of its state parliamentary advisory committee. Clem was elected unopposed to the office of state president of the ALP for a year in 1956, after a time as the party’s senior vice-president of the South Australian ALP, and while still state secretary of the VBEF. The official organ of the UTLC, the Herald, proudly noted that Clem belonged ‘to a very small and select band’ who had held the ‘twin’ positions of state ALP president and president of the South Australian UTLC.

A member of the Fabian Society, a devoted follower of former Labor Prime Minister Ben Chifley, and a friend of the moderate trade union leader, Albert Monk, Ridley opposed militancy in the unions and the extremes of anti-communism. In 1958 the ALP rewarded his long service to the party and to the labour movement by preselecting him for the Senate. In his campaign speech, he referred to Labor’s pledge to restore and revitalise the economy through a return to full employment and a restoration of the purchasing power of child endowment, age and invalid pensions and other social service payments. Elected at the federal poll of 22 November 1958, he was sworn in the Senate on 11 August 1959, and re-elected in 1964. [1]

In his first speech during the 1959 budget debate, Ridley referred to the effect of sales tax on the motor vehicle building industry in South Australia, basing his carefully prepared and cogently argued case on his hands-on knowledge of the industry. He particularly objected to motor vehicles being categorised as ‘luxury’ items. Referring to dismissals at Chrysler Australia Ltd, he said that in South Australia ‘the new definition of an optimist was a man who took his lunch to work at Chrysler’s’.

Speaking against the Sales Tax (Exemptions and Classifications) Bill (No. 2) 1960, he opposed the bill’s increases in sales tax on cars from 30 to 40 per cent, sympathising, he said, with Government members who, though loyally voting for the legislation, would have voted against it had the proposal been placed before them prior to its introduction. In this, he doubtless included Senator Nancy Buttfield, the daughter of his previous employer Edward Holden. Ridley argued that the legislation was inflationary and would affect the competitiveness of the Australian motor industry, citing Liberal senator, Reg Wright, who with Ian Wood would join the Opposition in voting against the bill’s second reading. While Ridley denied being an apologist for GMH, having, as he said, for many years argued against that company from ‘the other side of the negotiation table’, he had nonetheless considerable loyalty to his old company. When the Country Party’s Senator McKellar attacked GMH for the manner in which it had dismissed its employees, Ridley rose in defence of the company, suggesting that GMH had treated its employees far better than had Ford or Chrysler.[2]

In 1961, in opposing the second reading of the Government’s Stevedoring Industry Bill, which introduced long service leave for waterside workers, albeit with penalties, Ridley found himself in company with Wright (a vehement anti-communist and totally opposed to the long service provisions) and also the DLP’s Senator McManus. ‘We are certain’, Ridley said, ‘that this legislation can do nothing but assist the Communist Party to retain power in the Waterside Workers Federation’, suggesting that some government senators were ‘providing themselves with a frozen asset [the communist bogy] that they can use at election time’.

During debate on a motion for the adjournment in May 1969, moved by Labor’s Senator Cohen for the purpose of discussing the Government’s failure to repeal certain clauses in the Conciliation and Arbitration Act, Ridley, sparring with McManus, darkly suggested that he knew to whom the communists gave their preferences. ‘Without the Communist Party’, he said, ‘the Democratic Labor Party would not exist’. Drawing on his experience in the VBEF, he then criticised elements within the trade union movement, saying that he had not had one strike during his ten years as secretary, but for the entire time had had ‘to put up with the interference of the Metal Trades Employers Federation’, which he considered ‘just as militant … as the Communist Party’.

Soon after entering the Senate, Ridley had spoken of his membership of an Australian trade union delegation, which included Albert Monk, and which visited the People’s Republic of China in mid-1957, at the invitation of the All-China Federation of Trade Unions. He made a point of identifying the respective communist and non-communist affiliations of the delegates. When Monk fell seriously ill during the trip, Ridley stayed on in China for a further six weeks until Monk had recovered. In 1965 he became a member of the Australian delegation to the twentieth session of the United Nations General Assembly in New York.[3]

Apart from industrial matters, Ridley was supportive of South Australian wine growing, and took a close interest in legislation concerning the River Murray, from 1968 serving on the Select Committee on Water Pollution. In 1964 Ridley became a temporary chairman of committees, a position he filled until 1971. In 1968 he was his party’s candidate for the post of Chairman of Committees, which he lost, conceding his defeat with his customary grace, to the Government’s Senator Drake-Brockman.[4]

Ridley was not preselected for the Senate election of November 1970 and left at the end of his term in 1971, along with his former VBEF colleague and lifelong friend, Senator Jim Toohey. While Labor literature gives Toohey his rightful place in preventing the Split in the ALP in 1955, it is hard to find a mention of Ridley. Yet, as Senator Murphy acknowledged, Ridley had played a significant role in the industrial and political arms of the ALP in South Australia, and in the Senate. In his quiet way, he helped to prevent Labor from tearing itself apart in South Australia.

Clement Frank Ridley died on 19 May 1988 in Adelaide, his wife Myrtle, née Jury, having died two years earlier. There were no children of the union, though he was fondly remembered by nieces and nephews.[5]

[1] The editor acknowledges the assistance of Brian Bingley, SLSA; Herald (Adel.), June 1998, p. 8, 14 Apr. 1950, p. 4; Advertiser (Adel.), 20 Sept. 1958, p. 23; Vehicle Builders Employees’ Federation of Australia, SA branch, Annual reports, 1955, p. 1, 1959, pp. 8–9; United Trades and Labor Council of South Australia, Minutes, 4 Feb. 1955, 17 Feb. 1956, SRG 1/1/18, SLSA; ALP, SA branch, Official reports of the 52nd–55th annual state conventions, 1955–58; Advertiser (Adel.), 5 May 1956, p. 3; South Australian Fabian Society, Minutes, 4 Sept. 1947, SRG 493/1/1, SLSA; Advertiser (Adel.), 18 Nov. 1958, p. 6.

[2] CPD, 27 Aug. 1959, pp. 362–5, 1 Dec. 1960, p. 1950, 5 Dec. 1960, pp. 2025, 2043, 24 Oct. 1961, p. 1420.

[3] CPD, 16 May 1961, pp. 1054–60, 21 May 1969, pp. 1445–7, 9 Nov. 1960, p. 1471; ACTU, Executive report, 1957, pp. 37–9, S784, NBAC, ANU; Vehicle Builders Employees’ Federation of Australia, SA branch, Annual report, 1957, pp. 19–23; Herald (Adel.), June 1988, p. 8; CPP, 320/1965.

[4] CPP, 98/1970; CPD, 16 Oct. 1963, pp. 1164–5, 21 Apr. 1970, p. 960.

[5] CPD, 12 May 1971, p. 1713; Advertiser (Adel.), 20 May, 1988, p. 4, 23 May 1988, p. 46, 24 May 1988, p. 40.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 3, 1962-1983, University of New South Wales Press Ltd, Sydney, 2010, pp. 217-219.