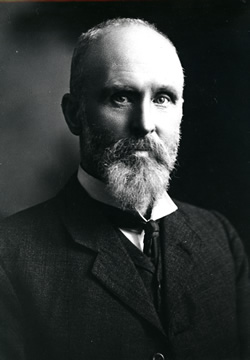

STEWART, James Charles (1850–1931)

Senator for Queensland, 1901–17 (Labor Party)

James Charles Stewart, an advocate of Scottish home rule, was born in Gorton, near Grantown‑on‑Spey, Morayshire, Scotland, on 7 September 1850. His father, Angus, was a farmer and blacksmith and his mother was Jessie Cruickshanks. Both lived in Gorton. James Charles attended the parish school until he was twelve, when he began work as a farm labourer. He must have continued some studies for at the age of sixteen he entered a solicitor’s office in Inverness as a law clerk. The indoor occupation adversely affected his health and after four years he returned to labouring, later working for the Caledonian Railway until he moved to Glasgow where he set up as a coal merchant. On 7 May 1880, at Oban, he married Mary McIntyre, a widow, according to the forms of the Established Church of Scotland. They had one son and three daughters, but in 1888 James left his family and migrated to Australia, settling in Rockhampton.

It is not known whether Stewart had been active in the Scottish labour movement but he certainly corresponded with the Scottish labour leader, James Keir Hardie, and was very quickly involved in the labour movement in Queensland. After working for some time on the Emu Park railway, he was employed in farming and fencing until 1893 when he became editor and business manager of the Rockhampton People’s Newspaper. He served as secretary of the Lakes Creek Labourers’ Union, the Butchers’ Union and the Rockhampton District Council of the Australian Labour Federation. From 1892 to 1896, he was an alderman on the North Rockhampton Council. He unsuccessfully contested the seat of Rockhampton North for the Legislative Assembly in 1893, winning that seat in 1896, and resigning in 1901 when he became a successful candidate for the Senate. Earlier, he had opposed Federation. As late as 1899, he had addressed an anti-Billite meeting in Rockhampton.[1]

Stewart was a member of the executive of the Federal Parliamentary Labor Party (1901–05 and 1914–17). He was elected secretary pro tem at its first meeting on 8 May 1901, and was Senate Labor Whip from 1901 to 1905. He was a member of the Senate library committee, and drew attention to the dearth of socialist literature in the Parliamentary Library. Among other committees on which he served was the select committee (converted to a royal commission) on the tobacco industry. Stewart supported the royal commission’s recommendation for the nationalisation of the tobacco industry.[2]

In the first Parliament, congratulated the Barton Government on ‘perhaps the most progressive, the most humane, and the most patriotic program ever presented by any Government to any Parliament’, but he warned that the most important question was that of coloured labour. He believed that legislatures moved too slowly. Labor wanted many reforms as quickly as possible and he hoped that the Senate would help to achieve them. ‘The Upper House’, he said ‘has always been looked upon as a brake on the wheel of progress. We have forgotten our brake. We have brought a stock-whip instead, and if things do not go as quickly as they should we will apply it’. When in August 1901, the House of Representatives carried a resolution advocating the transfer to the Commonwealth of full powers over wages and hours and conditions of labour, Stewart successfully moved a similar motion in the Senate. He saw the Commonwealth Parliament as ‘the only legislative body which has within itself the capacity to deal in a large, comprehensive, and final way with a question which closely affects the industrial life of the entire continent’.[3]

Stewart was always one of Labor’s most outspoken senators. Often critical of Britain, he was opposed to appeals to the Privy Council, and urged the need for the development of an Australian citizen army. In 1914, he successfully moved an amendment to the Defence Act to prevent the use of the Commonwealth’s citizen forces in industrial disputes. He insisted on the banning of coloured crews on mail ships. He supported a motion advocating home rule for Ireland. He stressed the need for Commonwealth public servants to have decent wages, reasonable promotion prospects and complete freedom of speech. H. G. Turner considered Stewart had ‘exceeded the bounds of decorum’ when he declared Sir Samuel Griffith to be unfit for the position of first Chief Justice of the High Court and a ‘self-seeker’ who had been faithless in his public duties. When Stewart suggested that parliamentary officers were overpaid and their remuneration so generous that he himself might consider applying for a parliamentary post, the Age observed: ‘The mantle of the humorist of the House is rapidly descending on Senator Stewart’.[4]

But Stewart was earnest in his desire for government economy. He saw the debate between free trade and protection as ‘merely a duel between the cities of Melbourne and Sydney’. For him, the real problem was that neither party was prepared to impose direct taxation to pay for popular measures, such as old-age pensions. The solution to increasing government revenue lay in land taxation, which he believed ‘to lie at the foundation of all the progress which Australia will ever be able to make’. It would, he said, ‘liberate the resources of the country . . . stimulate business, circulate money, and quicken the blood of the nation’. When a Labor Government introduced a land tax he considered that it was too low to achieve the break-up of large estates and check the growth of cities.[5]

With the advent of World War I, Stewart criticised government financial policies more persistently. He supported the war, though he hoped that it would mean the end of all monarchies (including the British) and declared that ‘fighting poverty within our own borders is even more important than fighting the Germans’. He opposed a grant of £100 000 to Belgium, drawing attention to unemployment, drought and declining revenue in Australia. He considered that Australia should concentrate on shore defence and equipment and could not afford naval expenditure. Stewart believed the conscription of capital was more important than that of manpower. He attempted to amend the conditions of war loans in order to lower the rate of interest and delay the payment of interest until five years after the war ended. Unless borrowing ceased and strict economy was practised, he predicted that Australia, ‘if not exactly in a ruined condition, will be practically an exhausted community’. He advocated breaking the monopoly on land and then using the land for soldier settlement. He considered that cities had grown out of all proportion, and deplored the power this gave to urban Australians and the politicians who represented them. He argued that Australia was ‘over rail-roaded’ and the transcontinental railway a ‘wild-cat scheme’, which had nothing to do with development.[6]

Though hoping for greater Commonwealth power to conduct socialistic enterprises, he was often critical of the existing forms of government. He thought that the Senate contained too many lawyers and objected to their being appointed to senior judicial positions. He considered that ministers were too often mere rubber stamps to enable permanent departmental officials to ‘rule the roost’. He thought senior bureaucrats were ‘largely responsible for the delay that takes place in dealing with the Estimates’. Regretting ‘the impotence of Parliament’ in relation to the executive, he wanted ‘not government by Ministers, but government by Parliament’. He spoke out about abuses of parliamentary procedure: ‘I wish once more to enter my protest against the suspension of the Standing Orders when we are dealing with matters of the gravest importance to the country’. He was impressed with the American system of parliamentary committees, considering it a useful model to follow in order to overcome the deficiencies of Australian and British parliamentary practice. In December 1914, he suggested an inquiry into parliamentary scrutiny of public spending, including the estimates process. Despite doubts about the appointment of the public works committee, he accepted membership of the first public accounts committee, his work there making him even more critical of Parliament’s lack of effective control over public expenditure.[7]

Throughout his career as a senator, he remained a member of Caucus. There have been suggestions that Stewart left the Labor Party at one time. I have found no evidence for this. He took an active part in the anti-conscription campaign. He denounced the Hughes Government as an ‘immoral fusion’, and in 1917 was defeated as a Labor candidate. On conscription, he said that he took a ‘frank survey of the situation’ and as this was the only disagreement he had with the Labor Party felt ‘it was my duty and my interest to stay where I was’. He was, he declared, ‘a soldier in the army of labour, and, like many other soldiers, I have, occasionally, to obey orders with which I may not agree; neither an army, a government, nor a country can be run on any other lines’.[8]

After his defeat he retired, first to ‘Mt Stewart’, a property near Yeppoon in Queensland, then in 1921 to ‘Kinrara’ near Farnborough where he bred Ayrshire cattle, and finally in 1925 to ‘Aldourie’ at Strathpine, near Brisbane, where he raised Leghorn fowls as a hobby. Although he remained a socialist, towards the end of his life Stewart’s views on some subjects underwent a transformation. Having in 1917, advocated the abolition of all monarchies, in 1930 he wrote to Sir Josiah Symon: ‘If I am a Jacobite I am not a bigoted one, and further I may tell you that I am not now a republican, although at one time I leaned very strongly that way. I consider that our present King [and his family] . . . have gone far towards rehabilitating the monarchy’.

Stewart died on 19 December 1931 at Strathpine, and was buried in the Lawnton Cemetery in Brisbane. His family never joined him in Australia and Mrs Stewart predeceased him in Glasgow in 1927. His son, also James Charles, and his daughters, Isabella, Jessie and Margaret, survived him. On Stewart’s death, a long-time colleague, Senator Matthew Reid said that he believed that Stewart’s ‘retiring disposition did not bring him to the position he deserved to have in the Party’. An unpublished typescript on Stewart concludes:

While countless nonentities gain illicit entry through the portals of posterity by way of names plastered on a multitude of plaques, posts and geographical points, men like James Charles Stewart who have led the workers through countless victories and many defeats in their biting, clawing, struggle towards a better concept of humanity die virtually alone, unremembered, unhonoured and unsung.[9]

[1] CPD, 7 March 1917, pp. 11056–11057; Morning Bulletin (Rockhampton), 7 April 1896, p. 4.

[2] L. F. Crisp, The Australian Federal Labour Party 1901–1951, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1978, pp. 111–112; Patrick Weller (ed.), Caucus Minutes, 1901–1949, Minutes of the Meetings of the Federal Parliamentary Labor Party, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1975, vol. 1, 1901–1917, pp. 490–491; CPD, 23 November 1905, p. 5676; CPP, Report of the royal commission on tobacco monopoly, 1906.

[3] CPD, 23 May 1901, pp. 266-274, 28 June 1901, pp. 1819-1820, 1826–1827, 9 August 1901, pp. 3552–3553, 3575; Geoffrey Sawer, Australian Federal Politics and Law 1901–1929, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1956, p. 29.

[4] Central Queensland Herald (Rockhampton), 7 July 1932, p. 12; CPD, 23 May 1901, pp. 268-270, 19 November 1914, p. 785, 7 March 1917, pp. 11056–11057, 12 December 1901, pp. 8626-8627, 30 January 1902, p. 9433, 24 September 1903, pp. 5441–5449, 20 June 1901, pp. 1362–1364; Henry Gyles Turner, The First Decade of the Australian Commonwealth, Mason, Firth & McCutcheon, Melbourne, 1911, p. 66; Age (Melbourne), 21 June 1901, p. 5.

[5] CPD, 23 May 1901, pp. 271-272, 25 June 1915, p. 4395, 2 September 1915, p. 6621, 22 May 1916, p. 8194.

[6] CPD, 22 July 1915, p. 5196, 9 October 1914, pp. 46–47, 26 June 1914, pp. 2629-2631, 28 July 1915, pp. 5357–5358, 14 March 1917, pp. 11441-11443, 14 December 1916, p. 9869, 28 July 1915, pp. 5386-5388.

[7] CPD, 14 December 1916, pp. 9870-9871, 14 June 1901, pp. 1147-1149, 10 December 1914, pp. 1474-1475, 10 May 1916, p. 7723, 9 October 1902, p. 16625, 28 July 1915, p. 5383, 18 December 1913, pp. 4688-4689.

[8] Weller, Caucus Minutes, p. 497; CPD, 9 February 1917, p. 10402, 14 March 1917, p. 11441.

[9] CPD, 14 March 1917, pp. 11438-11439; Letter, Stewart to Sir Josiah Symon, 1 September 1930, Symon Papers, MS 1736, NLA; Queenslander (Brisbane), 24 December 1931, p. 9; James Larcombe, Notes on the Political History of the Labor Movement in Queensland, Brisbane, 1934, p. 115; Central Queensland Herald (Rockhampton), 7 July 1932, p. 12; L. D. Mather, ‘James C. Stewart: A Biography’, unpublished typescript, John Oxley Library, SLQ, p. 5.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 100-103.