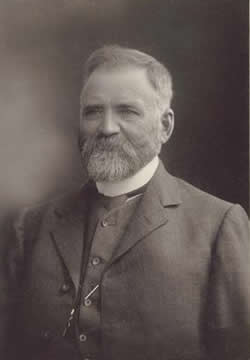

RUSSELL, William (1842–1912)

Senator for South Australia, 1907–12 (Labor Party)

Known for his ‘rugged native eloquence’, William Russell, a ‘practical farmer’, came to the South Australian and Commonwealth parliaments through his empathy with the farming communities of South Australia and his consequent involvement in rural politics. He was born in Glassford, Lanarkshire, Scotland, on 20 October 1842. That his father’s name was Matthew Russell is all that is known of his parents, who died when he was a boy. At the age of thirteen, William started work as a farm labourer. Later he decided to emigrate, and in 1866 arrived in South Australia on the sailing ship, Peeress. He became a farm hand at Alma Plains, and within three years was one of the first selectors on the Gulnare Plains, near Georgetown, moving on to Caltowie, Belton and Belalie. A vigorous member of the South Australian Farmers’ Association, he was also active in the work of district councils, serving between 1883 and 1885 as chairman of the Carrietown, Appila-Yarrowie and Caltowie branches respectively.[1]

It was his first-hand experience as a selector that led to Russell’s resolution that he should enter Parliament in order to reform South Australian land settlement legislation. In 1890, having the previous year been prominent in persuading the South Australian Government to supply seed-wheat to hard-pressed farmers in the north of the colony, he stood, unsuccessfully, for the seat of Newcastle in the House of Assembly. In 1894,he was elected to the Legislative Council as an ‘advanced’ Liberal.He remained on the Council representing the North Eastern District until 1900, finally winning the Assembly seat of Burra at a by-election in June 1901.

The greater part of Russell’s period in the South Australian Parliament coincided with the term of Kingston’s Liberal Ministry to whose progressive measures Russell lent his support. These included womanhood suffrage, the Married Women’s Protection Bill and the extension of the Legislative Council franchise, but his greatest concerns centred on South Australia’s small farmers. He spoke vehemently against the ‘best land’ being ‘locked up by large holders’, and in favour of a progressive land tax. His membership of several South Australian select committees and commissions included the House of Assembly’s taxation acts commission (1900) of which he was chairman.

Standing at the 1902 election, he was defeated, as he was again in 1905. At the latter election, he had become the official candidate of the Labor Party having been won over in 1904 by the Party’s inclusion of progressive land tax in its platform. Russell had now moved away from his 1895 declaration to the Legislative Council that he received no instructions from any party or clique, though as the Worker commented, he had ‘always been the friend and ally’ of the Labor Party. At the 1906 federal election, he stood as one of Labor’s candidates for the Senate and was successful.[2]

‘Before I entered this Senate’, pronounced Russell, ‘I was always under the impression that party politics should be unknown in a Chamber of this kind, and that it was not the province of a Senate, or within its power, to make or unmake Ministries. I really thought it was the duty of the Senate to look after the particular interests of the States . . . ’. While he spoke often of South Australia—proudly commenting that he had been a colonist for nearly forty-one years—his discomfort with party politics went beyond the role of the Senate to his own independent spirit and his desire to give the electors ‘something of the views of William Russell’. He once recited to senators a few lines from Robbie Burns: ‘Ye see yon birkie, ca’d a lord, Wha struts, and stares, and a’ that . . . The man of independent mind, He looks and laughs at a’ that’. In the debate on the Manufactures Encouragement Bill of 1908, he spoke scathingly of those who sacrificed their principles for ‘the sweets of office’. He explained that an eight-hour day was impracticable on a farm and spoke of his outback life in the north of the state. He told the Senate he had been ‘both a farm labourer and a farmer employing labour’. He considered that the South Australian Legislative Council, representing ‘landlordism in the extreme’, should be abolished, though he reassured senators that he was not ‘speaking of the Senate’.[3]

He continued to address those subjects that had engaged his attention in the South Australian Parliament, especially progressive land tax. For Russell, it was not simply that the big landholders of South Australia were holding on to the best land and so disadvantaging small farmers; they were also, from their privileged seats on the Council, hindering democratic reform. However, the land tax, which he and others in the Labor Party had hoped would break up large agricultural properties, did not eventuate, the Land Tax Bill of 1910 being simply a bill to raise revenue.

Russell supported old-age pensions for women as well as men, was in favour of compulsory voting, and though opposed to compulsory military training thought Australia ‘a good country’ and worth defending. He considered that defence expenditure should be raised by direct taxation: ‘If we find the bone and sinew to do the fighting, those who have large estates to be protected ought to find the necessary money . . . ’. Supporting the Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Bill of 1910, he attacked again the South Australian Legislative Council, this time for its failure to implement legislation on the wages boards. He held to the concept of a ‘fair and living wage’, especially in relation to ‘primary producing interests’, and in 1908 declared that despite some reservations he would ‘support the new protection throughout’. He seemed pleased that ploughs would be cheaper. In his speeches on the schedule of the Customs Tariff Bill, he expressed his concern for farmers. In 1911, he supported the Kalgoorlie to Port Augusta Railway Bill, his preference being for a 5 ft 3 in. railway gauge for the South Australian section. Russell, who had twice visited the Yass–Canberra area in 1908, came down firmly on the side of Canberra as the federal capital site. He assessed the water supply with the eye of the experienced farmer, giving the Senate a breakdown on the annual rainfall of the area between 1895 and 1906. He said he could not ‘forget Canberra’, recalling an interview he had there with the local miller.[4]

Like others in the early federal parliaments, he saw Australia as setting a democratic example to other nations. Lending full support to the resolution passed in 1910 by the all-male Senate in support of womanhood suffrage in Britain, he outlined South Australia’s proud achievement in granting womanhood suffrage in 1894–95, and discoursed on its ‘moral’ effects. In 1911, he moved the Address-in-Reply in the Senate, which he considered an honour to himself and to his state. He commenced by speaking of his pride that the Prime Minister, ‘Mr Fisher’, a coal miner, and his colleague, Senator Pearce, ‘the son of a blacksmith’ and himself a carpenter, had acquitted themselves well on the visit to London for the coronation of King George V, exclaiming: ‘a carpenter working for his living, dining with the King and the Queen . . . oh, was it not too much?’[5]

Russell did not complete his six-year term in the Senate. Speaking at political meetings in South Australia on behalf of Alexander Poynton, a South Australian Member of the House of Representatives, he was taken ill at Tumby Park and died at a private hospital there on 28 June 1912. On 25 February 1874, he had married Elizabeth Weir, née Kerr, at the Ardtornish School, near Adelaide. Russell’s wife, the couple’s two sons and four of their five daughters survived him.

In the Senate, colleagues on both sides of politics spoke of him warmly as ‘the architect of his own fortune’, a man who had risen in the world, but whose sympathies were with ‘the poor and distressed’. Russell’s strong Presbyterian faith included the belief that the Church should take an active role in affairs of state. In 1909, grieved by the plight of Port Pirie miners afflicted with lead poisoning, he pronounced: ‘when the law of God is concerned and the health and interests of the human family are affected, the Church ought to show its interest in the workers and in the cause of humanity’. He supposed, without a shred of evidence, that some of the clergy may have had shares in the mine![6]

[1] Register (Adelaide), 29 June 1912, p. 15; Advertiser (Adelaide), 18 May 1894, p. 2; H. T. Burgess (ed.), The Cyclopedia of South Australia, vol. 1, 1907, Cyclopedia Company, Adelaide, pp. 178–179; Register (Adelaide), 29 June 1912, p. 15; Information from the Northern Areas Council, SA, the City of Unley Museum and, on the South Australian Farmers’ Association, SLSA.

[2] Advertiser (Adelaide), 22 May 1894, p. 7; Register (Adelaide), 29 June 1912, p. 15; Burgess, The Cyclopedia of South Australia, p. 178; SAPD, 12 June 1894, pp. 10–14, 29 October 1896, pp. 270–271, 7 July 1896, p. 64, 24 July 1901, pp. 27–28; SAPP, Report of the Taxation Acts commission, 1900; D. J. Murphy (ed.), Labor in Politics: The State Labor Parties in Australia 1880–1920, UQP, St Lucia, Qld, 1975, pp. 254–255; CPD, 26 October 1911, p. 1841; SAPD, 3 July 1895, p. 368; Worker (Sydney), 15 April 1905, p. 2.

[3] CPD, 5 July 1907, pp. 141–144, 5 September 1911, p. 13, 2 December 1908, p. 2504, 18 August 1910, p. 1706, 5 July 1907, p. 143.

[4] CPD, 27 May 1909, p. 76; Geoffrey Sawer, Australian Federal Politics and Law 1901–1929, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1956, p. 91; Clyde Cameron, How Labor Lost its Way, Henry George League, Melbourne, 1984; CPD, 4 August 1910, p. 1072, 5 July 1907, p. 147, 11 November 1909, p. 5672, 17 September 1908, p. 97, 27 May 1909, p. 75, 10 August 1910, p. 1328, 18 August 1910, pp. 1705–1707, 5 July 1907, p. 141, 23 January 1908, p. 7596, 30 November 1911, p. 3419, 27 May 1909, p. 78, 20 October 1909, pp. 4705–4706, 27 May 1909, p. 78.

[5] CPD, 17 November 1910, pp. 6306–6308, 5 September 1911, pp. 11–12.

[6] Register (Adelaide), 29 June 1912, p. 15; CPD, 3 July 1912, pp. 356–358, 27 May 1909, pp. 73–74.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 176-179.