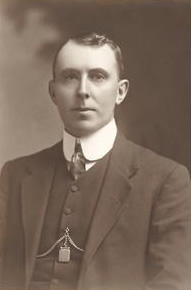

BLAKEY, Albert Edward Howarth (1879–1935)

Senator for Victoria, 1910–17 (Labor Party)

Albert Edward Howarth Blakey was born on 9 November 1879, at Balmoral, in the western district of Victoria, the son of William Henry, a fellmonger and later a wool-classer, and Louise, née Woodford. William appears to have emigrated to Australia from Huddersfield, Yorkshire, England, marrying Louise at Balmoral in 1878.

The young Blakey read widely and later lent his support to government increases to the Commonwealth Literary Fund. He was initially articled to a civil engineer, and worked in the regional township of Hamilton as a clerk. He returned to this employment at the end of his parliamentary career. Blakey had involved himself with the Victorian Clerks’ Union from its infancy and was active in the Australian Railways Union. Secretary of the Hamilton branch of the Labor Party from 1906, he attended annual conferences of the Victorian Labour Party—then known as the Political Labor Council—from 1907 to 1909 and in 1911. He served as an executive member of the Victorian State Labor Party from 1908 to 1910.[1]

Blakey began his formal political career as a candidate in 1907 and 1908 for the Victorian Legislative Assembly seat of Dundas, which centred on Hamilton. Unsuccessful on both occasions, he campaigned on the issue of land settlement, and in particular, land taxation, to break up rural estates and promote closer settlement in a region of large agricultural holdings. He numbered graziers and unionists among his friends, and his opponents urged voters to separate his affability from his Party’s policies.[2]

Blakey entered the Senate at the general election of 1910, when all eighteen Senate vacancies were filled by Labor candidates and, for the first time since Federation, a Labor Government held a clear majority in both Houses. In his first speech, he reflected on important elements of the Government’s programs for Commonwealth-state finances, land settlement and land tax, compulsory military training, invalid pensions and the lowering of the age at which women were eligible for old-age pensions. He was against Yass–Canberra as the capital site.

Speaking as ‘a young Australian’, Blakey declared that he would not be ‘bound’ by Caucus rule. A self-proclaimed ‘Labour moderate’ on questions other than those ‘embraced within the platform’ to which he subscribed, at times he criticised Labor policy administration. He questioned the imbalance between government expenditure on rural and city capital works in Victoria, and expenditure on the federal capital site. He also persistently queried the adequacy of the Government’s protection and extension of industrial award conditions. In 1912, he staunchly supported the Maternity Allowance Bill, denouncing the ‘whited sepulchres’ of the Church, some of whom it appears were opposing the Government’s intention to extend the benefit to unmarried mothers. ‘Why’, he declared, ‘should any restriction be placed upon any woman who has to suffer the same pains, pangs, and penalties, whether married or single?’ He was glad, he said, ‘that the trend of Australian thought is working in the direction of assisting those who need it’.[3]

The 1913 election resulted in a Senate of twenty-nine Labor and seven Liberal members for the remainder of the Liberal administration. Blakey was interested in the development of Papua and the Northern Territory, and supported the extension of railways in the Northern Territory as a means of encouraging cattlemen, miners and small landholders. He visited both places and developed a detailed knowledge of infrastructure and labour problems, once claiming to be ‘one of the non-official members of the Northern Territory’. He dismissed the contentious issue of the suitability of tropical settlement for Europeans and argued that the ‘white race is quite capable of overcoming the various difficulties’.

Blakey sought an entrepreneurial role for government, such as the construction of the meat works at Darwin and exploring for and developing oil production in Papua. He suggested that, with the proposed transcontinental rail link between north and south, the time was right to consider a standard national gauge.

Blakey, a member of the Senate select committee inquiring into the dismissal of Mr Chinn, a supervising engineer on the transcontinental railway, considered the Government’s handling of the Chinn case, a ‘mare’s nest’, and supported the committee’s recommendation for Chinn’s reinstatement and compensation. (The committee also admonished relevant government departments for deficiencies in providing it with information.) In 1913, Blakey, later a member of the joint committee of public accounts, accused the Government of hypocrisy in doubling the amount set aside for the capital site.[4]

Following the double dissolution in 1914, Blakey was elected to his final term at an election which gave a resounding win to Labor. One of the most regular in his attendance in the Senate, Blakey persistently questioned the Government on wages and job security for Commonwealth and other employees. For instance in 1915–16, he spoke of potential industrial unrest amongst the ‘girls’ in the Commonwealth Clothing Factory. In 1917, he noted: ‘I am here as a supplicant to the Government to consider the serious state of the building trades in Victoria’. Blakey had embarked on a critique of Labor’s wartime policy as early as October 1914, when he argued against the Australian Government’s grant to Belgium on the grounds of limited available resources and drought conditions within Australia. While he avoided the fractious debates within the Government between supporters of the war and those who promoted a domestic policy orientation, he criticised wartime policies such as the allowance of a tax exemption for interest on war loans.[5]

Blakey contributed most to debate amid the dissent in 1916 over conscription. While a ‘supporter and upholder of the views held by Mr. Hughes’, he opposed conscription. When confronted with accusations that he had supported the referendum proposal in the Labor Caucus, he argued that, with the prevailing censorship under the War Precautions Act, the anti-conscriptionists would not get a fair hearing. At the 1916 conference of the Australian Natives’ Association (ANA), Blakey, as the ANA’s senior vice-president, supported an unsuccessful amendment to curtail a motion of support for conscription. In the following year, he was narrowly defeated in the election for ANA president and declined to stand for further office.[6]

Following the Labor split over conscription, and the formation of the National Labor Government under Hughes in November 1916, Blakey remained with the Labor Party and argued stridently against Hughes’ leadership and wartime censorship regulations, accusing Hughes of sheltering behind the imperial authorities. At the 1917 election, Blakey was defeated, despite being placed second on the Labor Party ticket. During the campaign, he defended himself against Hughes’ accusation that he was opposed to winning the war. The Victorian Clerks’ Union nominated Blakey to again stand for the Senate at the 1925 election. He was preselected from a field of forty-two nominees, but was defeated.He was again unsuccessful as a Senate candidate in 1928.[7]

In 1912, Blakey had married Elsie Marguerite, née Hines, in the Roman Catholic Church of St John the Baptist in the Melbourne suburb of Clifton Hill. They had one son, Albert William Joseph, born in 1913. Blakey died at Mooroopna hospital on 4 July 1935, after a long illness. His wife and son survived him. He was buried with his parents in the Methodist section of the Brighton Cemetery. The flag above the Melbourne Trades Hall flew at half-mast for Blakey, and the delegates at a Trades Hall Council meeting stood in silence as a mark of respect. In 1912, Punch commented: ‘No man who stood for the Senate was better known all over Victoria, and everywhere his reputation was the same as in Hamilton—that of a straight, courteous, conscientious man, who could be trusted to do his best for the country’.[8]

[1] Australian Worker (Sydney), 10 July 1935, p. 14; CPD, 13 December 1911, p. 4220; Political Labour Council of Victoria, Central Executive, Minutes, SLV; Australian Worker, 3 May 1917, p. 7.

[2] Punch (Melbourne), 25 January 1912, p. 116; Hamilton Spectator, 28 December 1908, 29 December 1908.

[3] Age (Melbourne), 5 July 1935, p. 11; Hamilton Spectator, 14 March 1907; CPD, 7 July 1910, pp.143–146, 14 September 1910, pp. 3030–3032, 16 August 1912, p. 2296, 13 December 1911, p. 4220, 3 October 1912, pp. 3776–3780.

[4] CPD, 27 September 1912, pp. 3570–3572, 4 December 1913, pp. 3715–3717, 31 October 1913, p. 2822, 29 July 1915, pp. 5468-5470, 16 December 1913, p. 4399, 23 May 1916, pp. 8335–8336; CPP, Report of the select committee on the case of Mr H. Chinn, 1913; CPD, 16 August 1912, p. 2298, 30 October 1913, pp. 2696–2697.

[5] CPD, 1 September 1915, p. 6508, 10 September 1915, p. 6898, 20 May 1915, pp. 3265–3266, 29 July 1915, p. 5485, 10 May 1916, p. 7735, 15 February 1917, p. 10530; L. F. Fitzhardinge, The Little Digger 1914–1952, William Morris Hughes: A Political Biography, vol. 2, A & R, Sydney, 1979, p. 32; CPD, 9 October 1914, p. 44, 22 May 1916, pp. 8249–8250.

[6] CPD, 23 May 1916, pp. 8348–8349, 22 September 1916, pp. 8937–8939; J. E. Menadue, A Centenary History of the Australian Natives’ Association 1871–1971, Horticultural Press, Melbourne, 1971, pp. 266–267, 357, 388.

[7] Political Labour Council of Victoria, Central Executive, Minutes, 6 February 1925, SLV; Bendigo Advertiser, 4 April 1917, p. 5; CPD, 8 February 1917, pp. 10314–10315.

[8] Age (Melbourne), 5 July 1935, p. 11; Argus (Melbourne), 5 July 1935, p. 8; CPD, 23 September 1935, p. 20; Punch (Melbourne), 25 January 1912, p. 116.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 311-313.