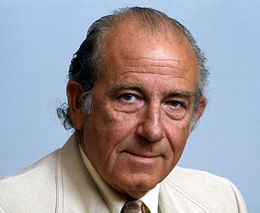

KEEFFE, James Bernard (1919–1988)

Senator for Queensland, 1965–83 (Australian Labor Party)

James Bernard Keeffe, champion of Indigenous Australians and the Deep North, was always proud of his Irish heritage. His great-grandfather had emigrated from County Tipperary in 1841 and settled in the Queanbeyan district of New South Wales. Jim’s father, also James Keeffe, moved to Sydney, and then to northern Queensland where he worked as a canecutter, coffee planter and tin miner. He married Augusta Holzapfel, and they had four children. Jim, the eldest, was born at Atherton on 20 August 1919.

After a few years the family moved south to Innisfail and later to Mothar Mountain, near Gympie, where James senior was engaged in banana growing as a share farmer and farm labourer. Jim attended the local state school, but left at the age of thirteen after his father was bankrupted during the Depression. He continued to study by correspondence while working in the Gympie district as a farm labourer and forestry worker. He also studied shorthand, read widely, and supplemented his earnings by freelance journalism and the writing of short stories. As a young man in Sydney, his father had been an active socialist and a friend of Jack Lang. Other members of the family were active in local government. Keeffe later claimed that reading the Bulletin, William Lane, Charles Dickens and Karl Marx had drawn him to politics, together with the personal influence of the local state Labor member, Tom Dunstan. He joined the Gympie branch of the Australian Labor Party in 1937. [1]

In early 1939, Keeffe joined the militia and in December 1941 he enlisted in the 9th Australian Infantry Battalion. He served with the AIF in New Guinea from July 1942 and was in the advance party at Milne Bay. A serious bout of malaria led to him being invalided home in 1943. He returned to New Guinea in late 1944 with the rank of sergeant, and was wounded in action in Bougainville in January 1945. He spent the rest of the war in military hospitals in Brisbane, being discharged from the AIF in October 1945. Keeffe never fully recovered the use of his right arm, and endured periods of considerable pain for the rest of his life. Keeffe was a member of the Returned Services League and held office at the sub-branch level, but by the 1960s he had became an outspoken critic of the league. He transferred his active allegiance to the Australian Legion of Ex-Servicemen and Women, serving as a delegate to its national congresses, and as a member of both the state council and national executive.[2]

On 25 January 1941 Keeffe married Elizabeth Merle Garrett in St Patrick’s Catholic Church, Gympie. They had two children and moved to Geebung in Brisbane in 1946. Keeffe ran a small business for a year, sold real estate and life insurance, drove a baker’s cart, and undertook a rehabilitation course in coopering. He also made a private study of industrial law and took a refresher course in shorthand. Appointed assistant state secretary of the Federated Coopers of Australia in 1949, he became its secretary in 1950. He resigned in 1951 to take up industrial research work with the Plumbers and Gasfitters Employees’ Union of Australia, where he remained for five years.[3]

After the war, Keeffe rejoined the Labor Party and in 1948 became the foundation secretary of the Geebung branch. He served for ten years as a delegate to the Lilley federal divisional executive, and helped establish the ALP youth movement. In March 1956 he defeated ten opponents and was elected state organiser of the ALP. It was a turbulent time, leading up to the Split in the party and Labor’s loss of government in Queensland in 1957. Although a Catholic, Keeffe was strongly opposed to the Industrial Groups and the defectors who, led by Vince Gair, formed the Queensland Labor Party. After the Split the ALP remained a divided party and Keeffe sided with the Trades Hall group, led by Jack Egerton, which challenged the hegemony of the Australian Workers’ Union. As state organiser, he travelled constantly throughout Queensland, building up the party’s strength in rural areas, seeking to win over disaffected members, and revive defunct branches. He relished the chance to do literary work, writing lengthy reports for Labor News, as well as articles on the history of the labour movement and occasional short stories.[4]

In August 1960, following the death of Jack Schmella, Keeffe was appointed state secretary of the ALP. A few weeks later, he became one of the two Queensland delegates on the Federal Executive. In the 1961 federal election, a huge swing to Labor in Queensland almost resulted in the defeat of the Menzies Government. Keeffe, as the campaign manager, was credited with much of the success and in particular was praised for innovations such as standardised how-to-vote cards and singing commercials. His rapid rise within the party continued. In July 1962 factional divisions and personal vendettas within the Federal Executive led to Keeffe being elected federal president of the ALP. He owed his position to the patronage of the federal secretary, the left’s powerbroker, F. E. (‘Joe’) Chamberlain, from Western Australia, and he always supported the left faction within the executive. His sudden elevation prompted a good deal of attention in the press. Commentators described him as modest, softly spoken, a tireless backroom worker and a master tactician, and some predicted that within a few years his would be a household name.

Keeffe enjoyed the work of state secretary and the close links with trade unions, but decided that he should enter Parliament by the time he was forty-five or not at all. He won second place on Labor’s Queensland ticket for the next Senate election and was one of two Labor candidates elected in December 1964. He subsequently resigned as state secretary.[5]

Elizabeth Keeffe died in July 1965. Later in the year, Keeffe moved from Brisbane to Townsville, where he was to live for the rest of his life. On 6 August 1966 he married his former secretary, Sheila Denise Nichols, in St Margaret Mary’s Catholic Church, Townsville. They had three children. Sheila shared her husband’s passion for politics, took an active part in ALP affairs, and was often photographed at party conferences with a baby in tow. In 1976 she was elected to the Townsville City Council. The marriage ended in divorce in 1981.[6]

Keeffe was sworn in the Senate on 17 August 1965. In his first speech, on 1 September, adapting words used by George Higinbotham, Keeffe said that ‘I intend to torment the souls of my political opponents’. He spoke frequently and often aggressively and he certainly irritated his opponents, although his speeches were poorly argued and unfocused and were likened by Magnus Cormack to ‘a brawling mountain stream’. He often digressed, was easily distracted by interjections, and rarely conceded that the arguments of an opponent might have some validity. Keeffe’s early speeches traversed a wide range of topics: the development of northern Australia, the state of the Royal Australian Navy, the social conditions of Aboriginal peoples, foreign ownership of oil and minerals, protection of the Great Barrier Reef, and the development of Papua New Guinea. The Vietnam War and Australian casualties were recurring themes. In October 1966 his support for anti-war demonstrations was described by John Gorton as a denial of democracy and when Keeffe angrily retaliated he was suspended from the Senate. It was to be the first of six suspensions over the next twelve years.[7]

Keeffe remained federal president of the ALP during his first five years in the Senate. He chaired the biennial federal conferences and the Federal Executive meetings with considerable flair. In 1962 Keeffe had been regarded as the quiet man of the ALP, but as federal president he became more loquacious and at times intemperate. He embarrassed ALP leader Arthur Calwell by calling the visit of President Johnson to Australia in 1966 ‘a cheap political gimmick’ and his opposition to the Vietnam War and to conscription was unequivocal. A conspicuous figure at marches and rallies throughout Australia, in 1970 he faced possible criminal proceedings for urging young men not to register under the National Service Act.[8]

His opposition to state aid to private schools was equally uncompromising and led to clashes with Labor leader Gough Whitlam. In 1966 Whitlam angered Keeffe by referring to the Federal Executive as ‘the twelve witless men’. Keeffe sent a telegram to the Queensland Central Executive urging that it request the Federal Executive to take ‘strong disciplinary action’ against Whitlam. Moves on the Federal Executive to expel Whitlam from the ALP seemed set to succeed by seven votes to five, but were then blocked reluctantly by Keeffe, and his fellow Queensland delegate, who changed their votes, acting on firm instructions from Queensland party secretary, Tom Burns. Keeffe’s relations with Whitlam remained strained. In 1968 they quarrelled over the removal of right-winger Brian Harradine from the Federal Executive, Whitlam arguing that ‘no delegate from any State [should] be tried by the Federal Executive without notice [or] charges’. When Whitlam resigned the party leadership in April 1968, narrowly defeating Jim Cairns in the subsequent leadership spill, he referred to lack of support from Keeffe, among others, as a reason for his resignation. Keeffe was lukewarm about Whitlam’s plans for party reorganisation and in particular opposed federal intervention in state branches. Only after he gave up the presidency in 1970 did the Federal Executive take control of the Victorian branch.[9]

Clyde Cameron later wrote that ‘Jim Keeffe learnt the danger of carrying the Presidential Staff when he entered the Caucus room’. Keeffe’s parliamentary colleagues saw him as the machine man and were angered when he lectured to them on party policy or attacked the veteran Allan Fraser (MHR Eden-Monaro 1943–66, 1969–72) over state aid. Keeffe was rebuffed on a number of occasions, most notably in March 1966 when he came last in the ballot for the Caucus committee on northern development. Gradually his abilities received some recognition. In 1967 he was elected to the Council of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, on which he served for eight years. From 1967 to 1971, as a member of the Senate Select Committee on Off-shore Petroleum Resources, he was one of the committee’s more outspoken members, interrogating oil company executives about royalty rates and cost price structures. In August 1970 Keeffe stood down as president of the ALP. In one valedictory, he was described as ‘a tough knockabout Australian bushworker, with his hat on the back of a head in which a shrewd brain never stopped working. [He] had aggression and pugnacity and courage, but he lacked finesse and polish’.[10]

Keeffe was assiduous in his attendance at Senate sittings. He handled a large correspondence with little secretarial assistance. He travelled each week between Townsville and Canberra and in the winter recesses drove long distances in northern and western Queensland and the Northern Territory, meeting party officials and supporters, as well as bush workers and Aboriginal leaders. On one such journey, in November 1972, his car overturned and he was badly injured. When, a few weeks later, Labor won the federal election, Keeffe’s hopes of becoming a minister were thwarted. Nine other senators were ahead of him in the Caucus ballot.[11]

In his new role as a government senator, Keeffe’s speeches and questions were far fewer and briefer, but he now had more chance to influence public policy through committee work. He was a member of the Joint Committee on the Northern Territory, which considered forms of self-government for the territory. He wrote a dissenting report, urging that six seats in the Legislative Assembly be reserved for Aboriginals, and he chaired one of the estimates committees which dealt inter alia with Aboriginal affairs. In March 1973 Keeffe became chairman of the Standing Committee on Social Environment, which spent three years investigating the living conditions of Indigenous peoples, its members visiting 110 localities in all states and the Northern Territory. Other members of the committee, such as Peter Baume and Neville Bonner were surprised to find that Keeffe was ‘a fair, just and reasonable’ chairman and as they travelled through rural Australia they developed a degree of camaraderie that was lacking in the Senate chamber. His work on the committee was part of an increasing preoccupation with the plight of Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders and his speeches, questions and writings concentrated on Aboriginal social conditions, health, land rights, wages, the protection of sacred sites and mining on Aboriginal lands. Above all, he constantly and virulently attacked the discriminatory policies of the Queensland Government and its administration of Palm Island and other Aboriginal reserves, which he visited many times.[12]

After Labor’s election loss in December 1975, Keeffe was elected Deputy Leader of the Opposition in the Senate in January 1976, defeating former minister Jim McClelland. Whitlam made him shadow minister for Aboriginal affairs and northern Australia. Keeffe’s success was unexpected and was due in part to the ‘cauldron of animosities’ in Caucus surrounding Whitlam’s leadership. By 1977 Keeffe and deputy leader of the party, Tom Uren, were supporting the leadership claims of Bill Hayden. Keeffe again became prominent in Senate debates. Convinced that the 1976 Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Bill gave excessive powers to the Northern Territory Legislative Assembly, which he believed was dominated by the mining lobby, he moved numerous amendments to protect sacred sites and wildlife and the rights of Aboriginals to enter pastoral leases. They were all defeated.

Keeffe was glad to return, by virtue of his post as Senate deputy leader, to the Federal Executive (now National Executive) and thereby to influence party policy. Colleagues regarded him as ‘a warm-hearted fellow totally lacking leadership skills’. Few were surprised when he lost the Senate deputy leadership to Doug McClelland in a ballot in May 1977.[13]

In his remaining years as a senator, Keeffe continued to be an unrelenting critic of the Queensland Government. He was a member of the Standing Committee on Constitutional and Legal Affairs, which considered the position of indigenous peoples in Queensland, and he took part in civil liberties demonstrations in Brisbane and Townsville. He continued to travel as much as ever around Queensland, which placed strains on his private life. A takeover of the Queensland branch of the ALP by the National Executive resulted in his appointment to an interim administrative committee that consumed much time and energy. Later in 1980, he decided to retire from the Senate, but was persuaded by Hayden to stay on.[14]

Following the double dissolution on 4 February 1983, Keeffe was concerned that some of the party leaders in Queensland were planning to displace George Georges from the head of the ALP ticket, and that he himself would be dropped to a lowly position. He was also convinced that the new leader, Bob Hawke, was intent on circumventing the state council in order to select more moderate candidates. On 7 February 1983 Keeffe caused confusion within the party by withdrawing his nomination. He urged that Georges remain as team leader and that the vacancy be filled by a woman. Some of his colleagues on the party’s socialist left were dismayed, but he achieved his wish: at the election on 5 March Georges headed the ALP ticket while Margaret Reynolds, also from Townsville, was in the fourth position.[15]

In vigorous retirement, Keeffe built a house on the outskirts of Townsville, where he grew orchids and spent time with his younger children. He remained on the state council of the ALP until 1985, contributed a political feature to a local weekly newspaper, and compiled a history of the Outward Bound organisation. Keeffe was a member of the Australian Littoral Society, the Wildlife Preservation Society of Australia and the Australian Conservation Foundation, and wrote several children’s stories with strong environmental themes. He visited his ancestral lands in Ireland. In 1988 he returned to Canberra for the opening of the new Parliament House on 9 May. On 15 May, he died suddenly, while travelling by train back to Townsville. After a Requiem Mass at St Joseph’s Church, Townsville, he was cremated. He was survived by Sheila and his five children.[16]

Keeffe said that he had a lot of fun in politics, and one political commentator wrote that he ‘lived his life in technicolor, enjoying every moment of it’. He was also described by a colleague as ‘a bloke of outspoken, almost suicidal integrity’. He was proud that he had helped to change party policy on the Vietnam War, the mining of uranium, and the cause of Aboriginals. In 1980 he noted that he had been castigated by ALP colleagues for his preoccupation with these causes. His response, which summarised his political credo, was that parliamentary members of the Labor Party had ‘a social and moral obligation to speak and work’ for the underprivileged, for the protection of civil liberties, for the protection of the environment, and for the right of all to a decent standard of living.[17]

[1] Canberra Historical Journal, Mar. 1981, pp. 10–19; James Bernard Keeffe, Transcript of oral history interview with Pat Shaw, 1985, POHP, TRC 4900/43, NLA, pp. 1:1–6, 2:12–13, 2:17, 2:19.

[2] Keeffe, James Bernard—Defence Service Record, B883, QX38055, NAA; Keeffe, Transcript, pp. 1:7–9, 9:10; Don Whitington, The Witless Men, Sun Books, South Melbourne, 1975, p. 28; CPD, 20 Oct. 1965, p. 1066.

[3] Letter, Keeffe to Kath Bloomfield, 3 Feb. 1983, James Bernard Keeffe Papers, ms 5135, box 373, NLA; Keeffe, Transcript, pp. 1:10–14; Federated Coopers of Australia, Minutes, 7 Jan. 1949, 6 Jan. 1950, 3 Aug. 1951, T50/1/10–11, NBAC, ANU.

[4] Keeffe, Transcript, pp. 1:14, 2:20–1, 4:1–2; Letters, Keeffe to Bloomfield, 3 Feb. 1983, Keeffe to A. Cole, 3 Aug. 1960, Keeffe Papers, MS 5135, boxes 373 and 356, NLA; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 20 Mar. 1956, p. 3; ALP, Official record of the 23rd Queensland Labor-in-Politics Convention, 1960, p. 74.

[5] ALP, Official record of the 24th Queensland Labor-in-Politics Convention, 1963, p. 123; ALP, Federal Secretariat, Federal Executive minutes, 5 Sept. 1960, MS 4985, box 123, NLA; Herald (Melb.), 14 Dec. 1961, p. 4; DT (Syd.), 6 July 1962, p. 3; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 6 July 1962, p. 3; Daily Mirror (Syd.), 25 Jan. 1963, p. 18; Keeffe, Transcript, pp. 4:16–17, 5:3–5.

[6] Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 30 July 1965, p. 30; Keeffe, Transcript, p. 5:5; Townsville Daily Bulletin, 6 Aug. 1966, p. 1; Biographical Notes—Sheila Denise Keeffe, 12 Jan. 1978, Keeffe Papers, MS 5135, box 80, NLA; The editor is indebted to Petrus Smith, Townsville City Council.

[7] CPD, 1 Sept. 1965, p. 263, 16 May 1968, p. 1113, 5 Oct. 1965, pp. 817–20, 11 Nov. 1965, pp. 1475–7, 25 Oct. 1966, pp. 1416–21, 28 Feb. 1967, pp. 163–4, 10 June 1970, pp. 2253–8, 11 Nov. 1965, pp. 1488–90, 26 Oct. 1966, p. 1427, 27 Oct. 1966, pp. 1500–1.

[8] Townsville Daily Bulletin, 7 Oct. 1966, p. 3; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 24 Sept. 1970, p. 3; CT, 19 Sept. 1970, p. 1.

[9] Keeffe, Transcript, pp. 4:4, 4:11–12; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 24 May 1988, p. 8; Whitington, The Witless Men, p. 47; Laurie Oakes, Whitlam PM: A Biography, A & R, Sydney, 1973, p. 140; ALP, Federal Secretariat, Federal Executive agenda, 27 July 1966, box 120, folder 42, Federal Executive minutes, 18–19 Apr. 1968, box 120, folder 45, MS 4985, NLA; Australian (Syd.), 5 June 2007, p. 1; Alan Reid, The Gorton Experiment, Shakespeare Head Press, Sydney, 1971, pp. 104–9; Graham Freudenberg, A Certain Grandeur: Gough Whitlam in Politics, Macmillan, South Melbourne, 1977, p. 133.

[10] Clyde Cameron, ‘The basic rules of politics’, Selected letters, vol. 26, 1994, p. 9, Clyde Cameron Papers, MS 4614, NLA; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 26 Mar. 1966, p. 3; Daily Mirror (Syd.), 18 Nov. 1965, p. 9; DT (Syd.), 24 Mar. 1966, p. 19; Nation (Syd.), 2 Apr. 1966, p. 12; Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Annual reports, 1967/1968, 1974/1975; CPP, 201/1971; Sunday Observer (Melb.), 16 Aug. 1970, p. 14.

[11] Letters, Keeffe to Fred Daly, 10 July 1973, 20 Dec. 1974, Keeffe Papers, MS 5135, box 47, NLA; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 13 Nov. 1972, p. 1; Australian (Syd.), 19 Dec. 1972, p. 2.

[12] CPP, 281/1974, 134/1975, 199/1976; CPD, 7 Dec. 1976, p. 2732; Angela Burger, Neville Bonner: A Biography, Macmillan, South Melbourne, 1979, p. 108; CPD, 14 Nov. 1973, pp. 1808–11, 5 Dec. 1974, pp. 3196–3200.

[13] Paul Kelly, The Hawke Ascendancy, A & R, North Ryde, NSW, 1984, p. 29; Tom Uren, Straight Left, Random House, Milsons Point, NSW, 1994, pp. 297–8; CPD, 7 Dec. 1976, pp. 2728–32; Letter, Keeffe to Neville Wran, 10 Feb. 1976, Keeffe Papers, MS 5135, box 200, NLA; Susan Ryan, Catching the Waves: Life In and Out of Politics, HarperCollins Publishers, Pymble, NSW, 1999, pp. 163–4.

[14] Ross Fitzgerald and Harold Thornton, Labor in Queensland from the 1880s to 1988, UQP, St Lucia, Qld, 1989, pp. 282–6; Letter, Keeffe to Bill Hayden, 24 July 1980, Keeffe Papers, MS 5135, box 375, NLA.

[15] Keeffe, Transcript, pp. 9:4–6; Fitzgerald and Thornton, Labor in Queensland from the 1880s to 1988, p. 326; Letter, Keeffe to Peter Beattie, 7 Feb. 1983, Keeffe Papers, MS 5135, box 359, NLA; CT, 8 Feb. 1983, p. 1.

[16] Keeffe, Transcript, pp. 9:9–10; Letters, Keeffe to Ann McCabe, 13 Sept. 1984, Keeffe to Joan Errington, 8 Oct. 1984, Keeffe Papers, MS 5135, box 373, NLA; ALP, Federal Secretariat, Senate candidates’ biographical details, MS 4985, box 427, NLA; Kevin Keeffe, ‘Senator James Bernard Keeffe’, Australian Aboriginal Studies, no. 2, 1988, p. 117; Townsville Bulletin, 16 May 1988, p. 1, 19 May 1988, p. 17.

[17] Whitington, The Witless Men, p. 27; Age (Melb.), 31 May 1977, p. 9; Statement by Jim Keeffe in standing for preselection for Senate team, 1980, Keeffe Papers, MS 5135, box 354, NLA.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 3, 1962-1983, University of New South Wales Press Ltd, Sydney, 2010, pp. 332-338.