WARD, Frederick Furner (1872–1954)

Senator for South Australia, 1947–51 (Australian Labor Party)

Frederick Furner Ward, businessman, socialist, union official and Labor functionary, earned several distinctions throughout his long and busy life. Dogged and loyal, he tried unsuccessfully to win a seat in Parliament for the Labor Party in South Australia for nearly forty years (1909–46). For most of that time he was active in the state branch of the party in one or other capacity, including serving as its secretary for an unbroken term from 1923 to 1944. In 1947, at the age of seventy-five, he became the oldest person to take a seat in the Senate.[1]

Ward was born on 11 May 1872 in Bowden, an inner and thoroughly working-class suburb of Adelaide, but at the age of six his parents, Frederick Rousseau Ward, and Eliza, née Sheils, moved out to Port Adelaide where Ward spent the rest of his life. His father, who was born in England, was a miller but, no less importantly, an avid reader. Frederick Furner left school (Port Adelaide Public School) at the age of fourteen. Starting as a clerk he rose to become an accountant, commercial traveller, and ultimately manager of the Adelaide branch of Malcolm Reid, a timber, iron and furniture business. In a testimonial, Reid declared that Ward had been the best traveller and manager the company had ever had. Ward left the firm to become ‘chief metropolitan and suburban traveller’ for Lion Timber Mills. He later became a property owner and landlord.

Yet Ward’s sympathies were not with the employers but with the labour movement. As a young man he read socialist texts, and was an admirer of English socialist Robert Blatchford. In 1888 he helped return George Feltham Hopkins to the South Australian Legislative Council as a working man’s candidate for Port Adelaide. Ward joined the United Labor Party at its inception in 1891. For most of his working life he was a member or official of one trade union or another—the Federated Sawmills and Timber Yards Woodworkers’ Association, the Agricultural Implement and Machinery and Ironworkers’ Association (AIMIA), the Australian Workers’ Union, and the Federated Clerks’ Union. He was for many years a leading member of the Port Adelaide Trades and Labor Council and for twenty-eight years a delegate to the United Trades and Labor Council. Ward claimed that when secretary of the AIMIA he suggested the idea of New Protection. He certainly seconded the successful resolution on the adoption of New Protection at the 1908 Political Labour conference.[2]

It was in the Labor Party, rather than the trade unions, that he more obviously made his mark. By the time he was elected secretary of the South Australian branch in 1923, he had served the party faithfully and well for more than thirty years. He was secretary of the South Australian Labor Party during some of the most turbulent years in its history. For more than twenty years he convened the Labor Ring, a forum held in the Botanic Park every Sunday afternoon. On many occasions he had to protect the speakers’ platform from the hostility of such radical groups as the Industrial Workers of the World and the Plebs League. Sometimes he even used physical force against them or called the police. During the Depression he had to protect the party office itself from unionists angry about either the policies of the state Labor Government or the charges the state branch of the party found necessary to levy on unions and workers. Ward vigorously defended the party from all who attacked it. By the late 1920s he had become a bête noire of the militant left in Adelaide.[3]

Moreover, Ward saw the Labor Party through one of its major schisms. By late 1931 the state branch was irrevocably split over how to deal with the economic problems posed by the Depression. There was the parliamentary party led by Premier Lionel Hill, the Lang Labor group led by the Bardolph brothers, who since a preselection dispute in 1929 were among Ward’s most bitter enemies, and the official Labor Party-cum-Trades Hall group whose public face was Ward himself. These were the state branch’s leanest years. Its membership dropped from about 30 000 in 1927 to less than 10 000 in 1933 and its income plummeted dramatically because many unions could not pay their sustentation fees. The party could not even support Ward’s position as a full-time secretary, nor that of the assistant secretary (a certain Miss Hanretty, renowned for reliability). At some point Ward, by now not only a successful businessman but also a property owner, had to pay his own salary as well as that of his assistant.

In the early 1930s Ward underwent something of a transformation. On the one hand he felt that his party had been betrayed by the state Labor Government, the leading members of which were attacking the party, and him, with the same vehemence as their allies—those conservatives promoting the Premiers’ Plan. On the other hand, the stark contrast between his own economic security and affluence and the joblessness and hopelessness of people he saw every day forced him to appreciate the effects of the Depression on the Labor Party’s traditional supporters. From this time Ward insisted that the party go back to its roots, be true to itself, and declare that it was and always had been a socialist party.

With the loss of its right wing—Hill and his supporters—the Labor Party in South Australia inevitably lurched to the left.[4] But the change in Ward’s political outlook was far more dramatic. Totally committed and as loyal to the party as ever, he threw himself into the causes then most dear to its most vociferous critics to its left. In 1942 he joined the Socialist League in South Australia and became its secretary.[5] When the state branch—unlike its counterparts in the eastern states—accepted affiliation with the Movement Against War and Fascism, Ward was happy to become president of what many in the party considered a ‘communist front’. In the late 1930s he was no less eager to become a member of the Australia-Soviet Friendship League, and was later chairman of the Adelaide branch of the Australian–Russian Society.[6]

Yet it was not his newfound interest in these groups but other factors that caused him to lose the secretaryship of the party at the state convention in September 1944, when he was opposed and defeated. The successful candidate, W. J. Welsh, was young, a Catholic, and an organiser for the Federated Clerks’ Union. Most people at the time believed that Ward should make way for a younger man. But a couple of years later the Catholic Social Studies Movement (The Movement) boasted that the replacement of Ward by Welsh was ‘a major victory’ in its fight against communism in the trade union movement and in the Labor Party. It is also true that for a brief period in the mid-1940s the Labor right acquired an influence in South Australia it had not had before and has not had since. It is possible, then, that Ward’s scalp was not only the first but also the last The Movement was to take in the South Australian ALP.[7]

But if the branch no longer wanted Ward as its secretary it was at last prepared to have him as a parliamentarian. He had made an unsuccessful bid for Labor preselection in 1909, and in 1912 was a candidate for the seat of Murray in the House of Assembly. He tried for the Legislative Council in 1918, as an independent candidate, and in 1921, for Labor. In 1931 and 1937 he made two attempts for the Senate. Finally in 1945, the party endorsed him for the third, and fairly safe, place on its Senate ticket, and in September 1946 he was swept into the federal Parliament by what one historian has described as ‘a flood tide for Labor’. Clyde Cameron (who was later to become the federal member for Hindmarsh and a minister in the Whitlam Government), who had most to do with drawing up the ticket, said the only thing Ward was expected to do was ‘put up his hand at the right time’. Few were surprised that during his four years in the Senate—from July 1947 to March 1951—he delivered only five speeches, asked a handful of questions, and served on one minor committee.

His speeches, while cogent enough, dealt less with the political issues of the day than with lauding the achievements of the Labor Party, and attacking the non-Labor parties. True, he denounced private banks and uttered a few hostile remarks about the Communist Party, but this had more to do with party solidarity than private conviction. Along with fellow left-winger Bill Morrow, Ward absented himself during the final passage of the Communist Party Dissolution Bill in 1950. By and large, he mouthed the phrases and slogans that one would expect of a Labor left-winger in the 1940s. Thus, in the interests of ‘the workers’, he defended heavy taxation, economic protection and bank nationalisation. He denounced the Liberals as a party ‘run chiefly by big business men who are intent only on making riches for themselves’. He scorned the Country Party for supporting the Liberals rather than Labor—because, after all, ‘the merchants always rob the farmers’, and likened private enterprise to ‘the feeding of pigs at a trough’. Like a good Labor man, he argued that ‘businesses are best run on socialist lines’. At the same time he did not want to abolish capitalism so much as to place a limitation on profits.

Coming from a lifelong businessman, Ward’s statements must have seemed incongruous. Even more so were his attacks on state upper houses. Legislative Councils, he declared, were ‘the most effective barriers to true democracy in this country’ and ‘an obstacle to development’. These chambers were ‘the friends of big business and the landlords’ and should be abolished. This was a strange stance for a man who was himself a landlord and had often referred to a seat in the South Australian Legislative Council as the ‘delight of my life’. He was more consistent when he attacked his favourite target, the press, which, he said, was always on the side of vested interests because its main source of revenue came from advertisements. His hostility to the press—again largely a product of Labor’s experiences during the Depression—led him to grossly exaggerate, even claiming that were it not for the influence of the press, the anti-Labor parties would never win a seat in Parliament.[8]

After the simultaneous dissolution of both houses of the Parliament in March 1951 Ward succeeded in gaining Labor re-endorsement, but, placed last on a ticket of six, failed to win back his seat. But he lost none of his enthusiasm for either politics or business. He helped the party’s campaign for a ‘no’ vote against the Menzies Government’s referendum to ban the Communist Party and he became heavily involved in a real estate firm, through which, however, he lost a lot of money.[9]

The other loves of his life were his family, Port Adelaide, books and sport. On 16 June 1897, he had married Jessie McInnes Fraser, the daughter of a well-known shipwright at Birkenhead and a fellow Presbyterian. They had a daughter, Marion Lena Fraser, and a son, Frederick Blatchford, and from the 1920s lived at Largs Bay. His wife and daughter regularly attended church. Ward, in earlier years, had been a member of the board of management of the Port Adelaide Presbyterian Church and superintendent of the Lefèvre Peninsula Presbyterian Sunday school. He was well known in the Port Adelaide district and was as devoted to it as he was to the Labor Party. At some stage he was president of the Port Adelaide branch of the Justices’ Association and for many years was the auditor for the Port Adelaide City Council. His principal solitary pursuit was reading. When he died he left a huge library consisting largely of works on history and politics. Gregarious and a compulsive organiser, he had founded the Port Adelaide Literary and Debating Society, becoming its secretary. He was actively involved in at least four other cultural organisations—the Port Adelaide Democratic Club, the St Andrew’s Literary Association, the Dickens Fellowship and the Workers’ Educational Association.

At the same time he was a keen player with, and later official of, several cricket clubs and one Australian Rules football club. From 1893 to 1894 he was secretary of ‘the Port Native Club’, which seems to have been the precursor to the West Torrens Football Club. For most of his life—that is, after ‘electorate football’ was introduced—he was a leading official and often cantankerous supporter of Port Adelaide. The club made him a life member in 1927. He also played cricket for Port Adelaide. He loved the game so much that in later life he founded his own club—the Ethelton Cricket Club—and occasionally paid well-known cricketers to play for it. It was while watching this team from the sidelines of Largs Reserve in October 1954 that he became ill. He died on New Year’s Eve at the age of eighty-two.

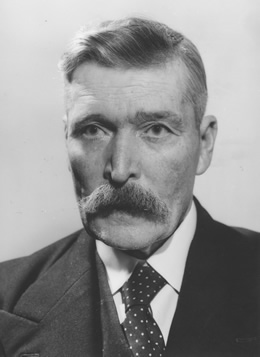

Ward looked like a successful businessman. Rather tall, he sat, stood and walked bolt upright, presenting a demeanour of great dignity. Always well groomed, he favoured tussore silk shirts, wore a tie, and walked around in well-polished shoes. His speech was laconic, his manners impeccable. From a young age he smoked cigars and carried an umbrella. Later, at least in summer, he wore a pith helmet. He always sported a moustache.

There are few memorials to Frederick Furner Ward. His funeral on 4 January 1955 was an impressive affair, with a large number of people from the Port Adelaide district turning out to watch the procession, and several Labor dignitaries, including state Labor leader, Mick O’Halloran, acting as pallbearers. His name appears on the Port Adelaide Workers’ Memorial, but his grave in Cheltenham Cemetery is unmarked. Ward’s remains lie alongside those of his wife. Nine years his senior, she had died only seven months earlier.[10]

[1] ‘Malcolm Saunders, ‘Never Favoured and Now Forgotten: A Tribute to “A Good Labor Man”’, Labour History, Nov. 1990, pp. 1–15; Joan Rydon, A Federal Legislature: The Australian Commonwealth Parliament 1901–1980, OUP, Melbourne, 1986, p. 52.

[2] Daily Herald (Adel.), 23 Jan. 1917, p. 6; Advertiser (Adel), 18 Dec. 1931, p. 27; Workers’ Weekly Herald (Adel.), 14 Aug. 1942, p. 4; CPD, 17 Oct. 1947, p. 929; Minutes of United Trades and Labor Council, SA, M15, Noel Butlin Archives Centre, ANU; ALP, Report of the fourth Commonwealth Political Labor Conference, Brisbane, 1908.

[3] Daily Herald (Adel.), 9 Feb. 1923, p. 2; Advertiser (Adel.), 9 Feb. 1923, p. 9; Labor’s Thirty Years’ Record in South Australia 1893–1923, Daily Herald, Adelaide, [1923], p. 64; Workers’ Weekly Herald (Adel.), 22 Sept. 1944, p. 1; John Playford, History of the Left-Wing of the South Australian Labor Movement, 1908–36, BA Hons thesis, University of Adelaide, 1958, pp. 53–4, 60, 73, 87, 95.

[4] Playford, History of the Left-Wing of the South Australian Labor Movement, pp. 54, 102; R. H. Pettman, Factionalism in the Australian Labor Party: A South Australian Case-Study, 1930–1933, BA Hons thesis, University of Adelaide, 1967, pp. 83, 91; Don Hopgood, ‘Lang Labor in South Australia’, Labour History, Nov. 1969, pp. 161–73.

[5] Letter, Bernice Jones (granddaughter) to author, Mar. 1988; Author interview with Clyde Cameron and Jim Toohey, Dec. 1988; Don Hopgood, ‘The View from Head Office: The South Australian Labor Political Machine, 1917–1930’, Politics, May 1971, pp. 70–8; Pettman, Factionalism in the Australian Labor Party, p. 108; Jim Moss, Sound of Trumpets: History of the Labour Movement in South Australia, Wakefield Press, Netley, SA, 1985, p. 335; Workers’ Weekly Herald (Adel.), 20 Nov. 1942, p. 8.

[6] David Rose, ‘The Movement Against War and Fascism, 1933-1939’, Labour History, May 1980, pp. 76–90; Workers’ Weekly Herald (Adel.), 19 Nov. 1937, p. 5, 26 Nov. 1937, p. 8; World Peace (Syd.), 1 Oct. 1938, p. 132; Jim Moss, Representatives of Discontent: History of the Communist Party in South Australia 1921–1981, Communist and Labour Movement History Group, Melbourne, 1983, pp. 26–9; Workers’ Weekly Herald (Adel.), 23 Oct. 1942, p. 5; Advertiser (Adel.), 24 Aug. 1948, p. 2.

[7] Workers’ Weekly Herald (Adel.), 15 Sept. 1944, p. 8; Advertiser (Adel.), 14 Sept. 1944, p. 5; Author interview with Cameron and Toohey; R. Hetherington and R. L. Reid, The South Australian Elections 1959, Rigby, Adelaide, 1962, p. 39; Catholic Action ‘At Work’, Australian Communist Party, Sydney, [1946], p. 12; Advertiser (Adel.), 10 June 1983, p. 7; Welsh had an unhappy time as secretary and resigned before the end of his term.

[8] Workers’ Weekly Herald (Adel.), 22 Sept. 1944, p. 1; Advertiser (Adel.), 4 Dec. 1931, p. 23; Workers’ Weekly Herald (Adel.), 12 Feb. 1937, p. 1, 26 Nov. 1937, p. 8, 9 Sept. 1938, p. 6; Brian McKinlay, The ALP: A Short History of the Australian Labor Party, Drummond Heinemann, Richmond, Vic., 1981, p. 95; Author interview with Cameron and Toohey; Advertiser (Adel.), 22 Mar. 1946, p. 9; SMH, 20 Oct. 1950, p. 1; CPD, 22 Sept. 1948, pp. 645, 648, 15 June 1949, p. 939, 17 Oct. 1947, pp. 929–30, 21 Nov. 1947, p. 2462.

[9] Herald (Adel.), 16 Mar. 1951, p. 4; Advertiser (Adel.), 19 Mar. 1951, p. 1; Moss, Sound of Trumpets, p. 374; Author interview with Fred Ward (grandson), Dec. 1988.

[10] A. M. Bray, Annals of the Port Adelaide Presbyterian Church, Grange, SA, c. 1999, pp. 66, 69-73, 92, 257, 267; Letter, Bernice Jones to author, Mar. 1988; Advertiser (Adel.), 18 Dec. 1931, p. 27, 1 Jan. 1955, p. 2; Information provided by John Sincock, Historian, Port Adelaide Football Club; Advertiser (Adel.), 14 Feb. 1939, p. 11; News (Adel.), 15 Nov. 1952, n.p.; Information provided by Sandra Morton, Local History Officer, City of Port Adelaide Enfield; Advertiser (Adel.), 5 Jan. 1955, p. 4.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 2, 1929-1962, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic., 2004, pp. 308-313.