O’SULLIVAN, Sir Michael Neil (1900–1968)

Senator for Queensland, 1947–62 (Liberal Party of Australia)

Solicitor and company director, Michael Neil (known as Neil) O’Sullivan was born on 2 August 1900 at Toowong, Queensland, the fifth child of Queensland-born parents, Patrick Alban O’Sullivan, a 37‑year‑old solicitor, and his wife Mary Bridget, née Macgroarty, twenty-nine, from Gympie. Neil was a descendant of an Irish Catholic family. His grandfather, Patrick (1818–1904), was a soldier, transported in 1838 for retaliating with his bayonet when struck by his officer with a sword. A staunch agrarian radical, Patrick prospered in the Australian colonies. Sharp with tongue and pen, he represented Ipswich (1860–63), West Moreton (1867–68), Burke (1876–78) and Stanley (1878–83, 1888–93). Neil had two uncles who were also engaged in the public life of Queensland. Thomas O’Sullivan (1856–1953) was a prominent barrister, Supreme Court judge, member of both houses of the Queensland Parliament and Attorney-General (1908–15). On Neil’s mother’s side there was Neil Francis Macgroarty (1888–1971), also a barrister and politician, who, as Attorney-General in the Country National Progressive Government of E. A. Moore (1929–32), had led for the Crown in the civil case associated with the 1930 Royal Commission investigating the conduct of two former Labor premiers, E. G. Theodore and William McCormack, over the Queensland Government’s purchase of the Mungana mines and Chillagoe smelters.

Neil O’Sullivan was thus a scion of an emergent Queensland Roman Catholic ex-Hibernian professional middle-class group whose initial significance tended to be concealed by the great political success of the Queensland Labor Party with its Catholic working-class adherents, and the post-1916 sectarianism of the Protestant middle classes.[1]

After primary education at Taringa State School, O’Sullivan enjoyed secondary schooling at St Joseph’s College, Nudgee, whose interests he later served as a foundation member, in 1922, of its Old Boys’ Association and as the association’s president (1940–41). Paying tribute to the college and the Christian Brothers as ‘that noble band, small in numbers, but strong in resolve, fervent in faith and unremitting in endeavour’, O’Sullivan, in 1941, bewailed the turning away from faith while ‘the spirit of revolt’ is abroad. Here were indications of a basic social and religious conservatism which flowered during the Cold War.

O’Sullivan served articles with legal firms in Brisbane and Warwick. Admitted as solicitor in December 1922, he did not hold an LL B as was commonly believed but passed the Solicitors’ Board examinations. He succeeded his father in the Brisbane practice and later formed a partnership with J. J. Rowell. On 3 April 1929 Archbishop James Duhig officiated at the marriage of O’Sullivan to Jessie Margaret Mary McEncroe, the eighteen‑year‑old daughter of a Toowong doctor. They were to have two sons, Michael, who became a barrister, and Patrick, a Jesuit priest. The connection with Duhig was close, and was maintained throughout O’Sullivan’s career. On matters of faith, morals, censorship and conservative Catholic social thought the two were as one.[2]

O’Sullivan made two unsuccessful attempts to enter federal and state politics. In 1934 he contested the federal constituency of Brisbane in the interests of the UAP and in 1941 he failed to win the Legislative Assembly seat of Windsor as a Country Progressive National candidate. His legal career and more particularly his business career, however, prospered. President of the Brisbane Chamber of Commerce (1936–37) and of the Property Owners’ Protection Association (1937–38), he concentrated on establishing himself as a leader of Brisbane’s mercantile sector.

On 8 May 1942, with the Japanese threat at its height, O’Sullivan, then aged forty-one, enlisted in the RAAF. Commissioned a month later, by the end of the year he was a flying officer, serving in intelligence and administration. John Gorton later recalled his first meeting with O’Sullivan when the latter was serving with the 75th Squadron at the RAAF base at Milne Bay, Papua New Guinea. O’Sullivan it seems was ‘well liked by all the pilots in the Squadron and those under his administration’, and ‘marked by being the only officer . . . who wore glasses secured by a thick black ribbon’. Army records, however, suggest that O’Sullivan, though able, did not take altogether kindly to military life. Discharged on 15 December 1944, he returned to legal practice, and at the 1946 federal election he won a Queensland Senate seat for the Liberal Party.[3]

With the Liberal Party’s Annabelle Rankin and the Country Party’s Walter Cooper O’Sullivan was one of the trio of Queensland senators who made up the entire Opposition in the Senate between 1947 and 1949. This made an immediate impact on his career; he became Deputy Leader of the Opposition from the time he took his seat in July 1947 until the 1949 election, when new electoral legislation began to effect changes in the composition of the Senate. While the Liberal–Country Party coalition won the 1949 election the Government lacked a majority in the Senate. O’Sullivan, who from December 1949 was Leader of the Government in the Senate, exhibited finesse, courtesy and a quiet and thorough forensic legislative and procedural skill that facilitated the Government’s business, as when in October, in an ‘unprecedented procedural drama’, he engaged in a battle of tactics with the Opposition as it tried (unsuccessfully in the end) to prevent the Government calling on a simultaneous dissolution. After the 1951 election, when the Opposition lost its Senate majority, he would be assisted by an increasingly fragmented and somewhat demoralised Labor Party.

His first speech in the Senate had reflected the enthusiasm of R. G. Menzies’ new Liberals, who were determined to roll back the ideas and institutions of a postwar reconstruction government that had ‘no right to assume to itself those functions properly belonging to the family, to the community, or to organized industry’. Yet before defending the war record of Menzies, bewailing the ‘betrayal’ of the Dutch in Indonesia, advocating a relaxation of taxation and clamouring for ‘anti-communist measures’, O’Sullivan delineated his core political philosophy:

I believe that man by his Creator is endowed with definite natural rights and is charged with equally definite obligations toward his Creator and his fellow men, that his prime purpose in life is the salvation of his soul, that the duty and responsibility of organized society is to ensure that, in the pursuit of life, liberty and happiness, man shall not be unduly frustrated [by Government].

On the Chifley Government’s 1947 Banking Bill, whose object was the nationalisation of banking, he referred to the Papal encyclical, Quadragesimo Anno, and its condemnation of socialism, and called on Labor senators to ‘give expression to their professions of humanity in the rich pasture of Christian justice and charity’. In a last ditch and unsuccessful effort to destroy the legislation, he moved an amendment against the motion for the third reading.[4]

As Minister for Trade and Customs from 1949 to January 1956, O’Sullivan was responsible for a literary and political censorship that some have thought paralleled that of de Valera’s Eire: ‘I am the final Court of Appeal’, O’Sullivan argued in 1952, adding ‘we need laws against indecency, blasphemy and sedition’. Similarly, when debating the Matrimonial Causes Bill of 1959 for which the Attorney-General, Garfield Barwick, was responsible, and which strengthened federal jurisdiction and loosened the legal straightjackets hindering the resolution of irretrievable matrimonial breakdowns, O’Sullivan stated that divorce was evil in itself, that it violated the Divine Law and that ‘a valid consummated Christian marriage is indissoluble’. Despite the allowance of a conscience vote, O’Sullivan ultimately voted with the Government’s legislation.

He was more fruitful pursuing trade in Australian primary products with his Country Party friend and confidant, Arthur Fadden, now federal Treasurer. In 1953 he was the official leader of the Australian delegation to London, which resulted in the International Sugar Agreement of that year and ensured Australia maintained its market for sugar in the postwar international scenario. With the Queensland Premier, V. C. Gair, and Agent-General, D. J. Muir, and advisers, O’Sullivan was successful in securing an agreement favourable to Australia (mainly Queensland). An apostle of the belief that family farm sugar production could secure the white man’s future in the tropics, improve the finances of Queensland and influence domestic processing, O’Sullivan, when international marketing was restructured as Britain moved to join the Common Market and abandon the ‘White’ Commonwealth’s specialist markets, became an avid supporter of subsidies, quotas and internal protection for Australian sugar. Here, as he acknowledged, he had much more in common with old Queensland Labor than his contemporary social politics suggested.[5]

O’Sullivan served in the Navy portfolio for some nine months during 1956, before going on to become Attorney-General. In 1954 he had urged the Prime Minister not to diminish the five portfolios then held by senators. As Attorney-General he chaired the Joint Parliamentary Committee on Constitutional Review (1956–59), established by his predecessor, Senator Spicer. ‘Though the mills’ of constitutional change in Australia ‘grind slowly’, O’Sullivan’s chairmanship of the committee was competent and creative, even though the result, at least initially, was politically sterile. The job also drew on his reputation for tact; committee members included the maverick Liberal senator, Reg Wright, who produced a dissenting report, and a strong Labor group, one of whom was the future Prime Minister, Gough Whitlam.[6]

The Senate was a volatile chamber in 1957, with senators on both sides disturbed by the diminishing authority of Parliament vis-à-vis the executive, with numbers of Government and Opposition senators at times evenly matched, with Labor facing internal division with the rise of the Democratic Labor Party, and with Liberals harbouring a number of ‘loose cannons’. In spite of all this, the Senate leadership on both sides remained strong; O’Sullivan’s period of continuous service was a record while Labor’s Senator Nick McKenna was a formidable opponent. An indication of the status of both can be seen in a ditty entitled ‘Neil and Nick’ appearing in the Sydney Sun, following the decision of fourteen Government senators (led by Senator Wright) to oppose the States’ Grants Commission (Salaries) Bill, which provided the executive, not Parliament, with responsibility for the salaries of commission members. The ditty, composed by ‘An Unknown Senator’, concluded thus:

And Reginald Wright then arose in a rage,

(John Pym and John Hampden awaiting off-stage)

He said: ‘of bureaucracy I’m fully sick,

But I’m sicker of Neil, and I’m sickest of Nick’.

. . . But the senators murmur

‘it’s just a bit thick

That nobody matters but Neil and old Nick’.

However, the relationship between the two leaders was not always so cosy, as when the Government’s fourteen bank bills were defeated in the Senate in December 1957.[7]

O’Sullivan’s views of the Senate—still worth considering within that institution’s last fifty years of change—are intriguing, if somewhat redundant at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Would any Australian prime minister or party chief since 1901 have agreed that no minister of the government should sit in the Senate and that senators should not attend party meetings but pursue an independent role, live in Canberra, have no compulsory retirement age and maintain a standard of debate which, O’Sullivan considered, was much higher in quality than that in the House of Representatives?

O’Sullivan left the Cabinet in 1958 ‘to make way for younger men’. Created KBE in 1959, in 1961 he let it be known that he would not be a candidate for the election that year. In retirement, he took up a considerable number of company directorships—the Atlas Royal Exchange Group, Amalgamated Petroleum, Queensland Press, Coachcraft and L. J. Hooker. An executive of the Royal Flying Doctor Service and the Boy Scouts Association of Queensland, he was a keen golfer, surfer and tennis player as well as a member of several Brisbane gentlemen’s clubs—but not the Queensland Club.

O’Sullivan died at the Carlton Rex Hotel, Sydney, on 4 July 1968, survived by his wife and sons. After a state funeral at St Stephen’s Roman Catholic Cathedral, where the Requiem Mass was celebrated by his son, Patrick, and his brother, and attended by Prime Minister Gorton, the Leader of the Opposition, Gough Whitlam, and a thousand other mourners, O’Sullivan was buried in the Nudgee Cemetery.

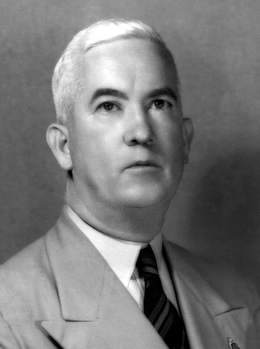

Sir Neil had a square, pink Irish-Australian face surmounted by a fine grey-white head of hair. Over six feet tall, he, the most mild and courteous of men, once threw a burly waterside worker off a political platform. Indeed, while he was an urbane, diplomatic and warm person ‘with an unfailing sense of humour’, he was a stern Cold War warrior and a staunch defender of both the rights of Queensland and the independence of the Senate from both party and the executive. While he believed that women senators did a fine job and could only enrich Parliament, he admitted to not wanting ‘to be flooded out by the stronger sex’. He was loyal, but not always acquiescent, to Menzies, and at heart believed that politics should be conducted and governments formed by alliances among gentlemen of property and education, socially conservative and of strict catechistic religious beliefs.[8]

[1] H. J. Gibbney, ‘O’Sullivan, Patrick’, ADB, vol. 5; Queensland Times (Ipswich), 25 June 1896, p. 2, 7 Apr. 1898, p. 7; Brian F. Stevenson, ‘O’Sullivan, Thomas’, ADB, vol. 11; K. E. Gill, ‘MacGroarty, Neil Francis’, ADB, vol. 10; K. H. Kennedy, The Mungana Affair: State Mining and Political Corruption in the 1920s, UQP, St Lucia, Qld, 1978, p. 95.

[2] Golden Jubilee of St Joseph’s College, Nudgee, 1891–1941, Strand Press, South Brisbane, c. 1941; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 1 Jan. 1959, p. 6.

[3] Queenslander (Brisb.), 19 July 1934, p. 33; A. L. Lougheed, A Century of Service: History of Brisbane Chamber of Commerce 1868–1968, Brisbane, 1969, p. 5; O’Sullivan, M. N.—War Service Record, A9300, NAA; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 5 July 1968, p. 3; CPD, 13 Aug. 1968 (R), pp. 3–9.

[4] Gavin Souter, Acts of Parliament, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1988, p. 380; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 5 July 1968, p. 3; CPD, 22 Oct. 1947, pp. 1048–55, 24 Nov. 1947, pp. 2513–20, 26 Nov. 1947, pp. 2706–9; J. R. Odgers, Australian Senate Practice, 5th edn, AGPS, Canberra, 1976, p. 324, 6th edn, Royal Australian Institute of Public Administration, Canberra, 1991, pp. 546–9.

[5] CPD, 25 Nov. 1959, pp. 1802–5, 27 & 28 Nov. 1959, pp. 2040–1; Letter, O’Sullivan to Menzies, 27 Apr. 1957, Personal Papers of Prime Minister Menzies, N2576, item 3, NAA; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 14 July 1953, p. 4, 26 Aug. 1953, p. 5; Cabinet Documents Relating to International Sugar Agreements 1950–53, A1209, items 1957/5623, 57/5628, A4940, item C488, A4905, item 554, NAA; CPD, 11 Mar. 1953, pp. 770–1, 9 May 1962, pp. 1238–43, 21 Mar. 1957, pp. 117–21.

[6] Don Whitington, Ring the Bells: A Dictionary of Australian Federal Politics, Georgian House, Melbourne, 1956, p. 91; Letter, O’Sullivan to Menzies, 2 June 1954, O’Sullivan Papers, MS 8639, NLA; CPD, 24 Oct. 1956, p. 896; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 3 Oct. 1958, p. 10; Age (Melb.), 29 Sept. 1958, p. 2, 14 Oct. 1958, p. 5; CPP, Joint Committee on Constitutional Review, reports, 1958, 1959; Geoffrey Sawer, ‘Reforming the Federal Constitution’, Australian Quarterly, Mar. 1960, pp. 29–33.

[7] CPD, 4 Sept. 1956, pp. 53–4, 5 Sept. 1957, p. 183, 1 Oct. 1957, pp. 272, 283; SMH, 2 Oct. 1957, p. 1; Sun (Syd.), 22 Oct. 1957, p. 28; SMH, 4 Dec. 1957, p. 11; Correspondence between O’Sullivan and McKenna, 20 & 25 Nov. 1957, 13 Mar. 1958, MS 8639, NLA.

[8] Herald (Melb.), 18 May 1962, p. 2; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 1 Jan. 1959, p. 1; Age (Melb.), 24 Nov. 1958, p. 1; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 9 Dec. 1958, p. 3, 14 Jan. 1961, p. 1; SMH, 5 July 1968, p. 4; CT, 8 July 1968, p. 6; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 5 July 1968, pp. 1, 3; ‘Meet the Press’, 2 Feb. 1958, MS 8639, NLA.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 2, 1929-1962, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic., 2004, pp. 367-372.