NEILD, John Cash (1846–1911)

Senator for New South Wales, 1901–10 (Free Trade)

John Cash Neild was born in the prosperous English port city of Bristol on 4 January 1846 to a surgeon of the same name and his wife Maria, née Greenwood, the daughter of a banker. In 1853, the family migrated to New Zealand, but the resurgence of war with the Maori led them to move to Sydney in 1860. Young Neild began work with an importing firm before establishing himself in 1870 as an insurance commission agent. Soon he was managing the Sydney offices of several English fire and accident insurance companies. On 29 October 1868, he married Clara Matilda Gertrude Agnew, daughter of Philip Agnew, the clergyman who founded the anti-papist Free Church of England in New South Wales, and Matilda, née Sutton. The only child of this marriage died in 1876; Clara died three years later. On 19 February 1880, Neild married Georgine Marie Louise Uhr, daughter of George Uhr, a former sheriff of New South Wales. Neild’s English birth and his early experiences and relationships through marriage shaped many of the attitudes he clung to throughout his adult life, notably his enduring love of England, his devotion to free trade, and his distrust of Catholicism.[1]

Like his father, Neild was blessed with an ability to speak and write fluently. He dabbled in literary and dramatic criticism and in poetry and, at the age of thirty, embarked on a political career. He served on the Woollahra Municipal Council from 1876 to 1890 and twice was Woollahra’s mayor. In 1885, he was elected to represent Paddington in the colony’s Legislative Assembly and held his seat intermittently until 1901. On entering Parliament, Neild supported Sir Henry Parkes and promoted his own unique combination of causes, especially free trade, old-age pensions, law and divorce reform, and state protection for children and the insane. His first speech on 20 November 1885 was a witty hammering of the government of George Dibbs. Better known was his performance on 23 June 1886 when he managed to speak for eight hours to delay the passage of a bill for customs duties. In January 1887, Parkes nearly chose him for his ministry. Neild reached high office outside Parliament when he served from 1891 to 1893 as Right Worshipful Grand Master of the Loyal Orange Institution of New South Wales.[2]

By then, Neild’s public career had begun to falter. He had revealed some alarming personal characteristics: poor judgement of men and situations, an exaggerated sense of dignity when in the public eye, verbosity, and a tendency to work himself to the point of physical prostration. His eight-hour speech had earned him the damaging name of ‘Jawbone’. His policy of ‘avoiding shabbiness’ during the erection of the New South Wales component of the Adelaide Jubilee International Exhibition of 1887 (when he was an executive commissioner) led to the appointment of a Legislative Assembly select committee. He was accused of extravagance and of having used his public office for profit. Neild was absolved from blame, but similar criticisms were heard again in 1899 when Premier George Reid paid him £350, without Parliament’s approval, toward costs he had incurred while writing a report advocating old-age pensions. Neild repaid the money, but the incident served as a pretext for bringing down Reid’s hitherto stable and effective government. Neild’s sole victory in colonial politics—divorce reform—occurred only because he was pressing a cause that was promoted by the respected Sir Alfred Stephen in the Legislative Council.[3]

Neild’s other public careers as writer, sectarian and citizen soldier were similarly troubled. A book of his poems, Songs ’neath the Southern Cross, was published early in 1896, many of its verses fulsomely praising Australia’s bushmen. The publisher, George Robertson, promoted the work as being on ‘a par with “The Man from Snowy River”’.

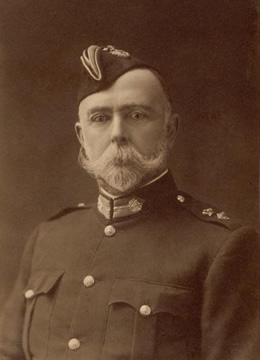

Neild proved too kind a man for real success in sectarian politics and outraged some of his colleagues by publicly praying to God to restore the Pope’s failing health. Yet it was probably sectarianism which prompted him to embark on his most disastrous public venture. Stung by the establishment of an Irish–Australian unit in New South Wales’ tiny part-time citizen army early in 1896, Neild raised what became the St George’s English Rifles, made up of men of various ethnic backgrounds who wished to demonstrate their love of Britain’s flag. Sydney soon became accustomed to the sight of Neild’s men, attired in a theatrical version of the uniform of Britain’s regular soldiers, marching from Circular Quay to the Domain to a musical arrangement combining the tunes of ‘The British Grenadiers’ and ‘The English Gentleman’. They were led by Neild himself, tall, broad-chested and affecting a fierce moustache. Within a month of raising the St George’s English Rifles, Neild ranked as a major; within two years he was a lieutenant colonel. He lacked both formal qualifications and the instinct for command, and plunged his unit into a series of disputes with the military authorities. There was also some dissension amongst his officers.

During Easter 1899, Neild was suspended from military duties for publicly criticising, and instructing junior officers to disobey, a staff officer. A subsequent military inquiry concluded that Neild was ‘a gentleman of no previous military experience . . . not amenable to discipline . . . who appears to lack the tact and judgement necessary to the efficient command of a Regiment’. Neild saved himself from dismissal by pouring time and money into the unit.[4] Antagonising the military authorities did not prove to be the end of Neild’s public life. In March 1901, he was elected a senator for New South Wales. Neild was, with Senator Cameron, one of two Commonwealth parliamentarians to wear full dress military uniform at the opening of Parliament in May 1901.

On 9 August 1901, Neild introduced his Parliamentary Evidence Bill—‘an absolute transcript’ of the New South Wales legislation—‘to enable and regulate the taking of evidence by Parliament and Parliamentary Committees’. The Bill was to have a chequered history. It was withdrawn during the 1901–02 session, reintroduced by Neild and discharged in 1903, initiated again by Neild and referred to the standing orders committee in 1904, and debated at length in the committee of the whole in 1905. Renamed the Parliamentary Witnesses Bill, from mid-1907 it became a Government Bill, although it remained, according to the Minister for Home Affairs, Senator John Keating, ‘practically a transcript’ of Neild’s 1904 Bill. Again it lapsed, suffering a similar fate on a number of occasions and finally disappeared from the Senate Notice Paper during World War I.

In May 1903, Neild spoke against the Government’s practice of having the Governor-General address only the ‘gentlemen of the House of Representatives’ when mentioning financial proposals. Neild was an active member on some of the Senate’s first committees, though his hopes of becoming deputy president and Chairman of Committees were dashed. However, from 1903 to 1910 he served as a Temporary Chairman of Committees.

Neild objected to strict party voting and rebelled against Josiah Symon’s autocratic leadership of the Free Traders in the Senate. He opposed as cowardly and ‘un-English’ the exclusion of non-British immigrants by a dictation test and the forcible deportation of Kanaka labourers. His opposition to high tariffs and advocacy of Australia-wide old-age pensions, his distrust of Federation, his uncomplicated loyalty to the British Empire and his championing of the rights of part-time citizen military officers over full-time staff officers may have contributed to his support among electors. Though failing in health, in December 1903 he was returned at the head of the New South Wales Senate poll.[5]

During an Address-in-Reply debate in March 1904, Neild denounced even more vehemently than usual, the ‘intolerable deficiencies’ of the Government’s military policy and of the military commander of the newly federated military forces, Major-General Sir Edward Hutton. Hutton had long wished to dismiss Neild from the citizen army, and Neild had recently provoked some members of the St George’s English Rifles to near mutiny by wrecking the military career of a loyal and well-known sergeant. Hutton now suspended Neild from duty and ordered another military inquiry into the management of his unit. Neild claimed the suspension was not an act of military discipline but an assault on a senator’s privilege to speak freely on all matters. On 20 April 1904, he persuaded the Senate to establish a select committee to investigate whether parliamentary privilege had been breached. (This was the only case, in the first sixty-five years of the Senate, of a Senate committee examining possible contempt of Parliament.)

Neild believed he had the upper hand over Hutton and fought frantically and even unscrupulously to prevent an adverse finding. His efforts were fruitless. On 20 October 1904, the committee reported that Hutton had acted partly because of Neild’s speeches in the Senate and partly for military reasons in recommending that Neild be placed upon the retired list. The committee concluded that Hutton’s action did not constitute intimidation. Neild permanently lost command of his unit in April 1905. He had already lost the respect of his fellow senators, who now taunted him without restraint. One of the kindest verdicts passed on him at this time was that he was ‘a decent, good-natured fellow’ but ‘verbose, vain, and politically an impossible person’.[6]

Neild was exhausted politically, emotionally and physically.He became a figure of fun, and quoting the worst of his poetry was an easy way to earn a laugh. During his remaining years in the Senate, he introduced a number of bills, all of which ultimately lapsed: the Parliamentary Witnesses Bill, 1905; Criminal Appeals Bill, 1907; Remuneration of Labour Bill, 1907; Invalid and Old Age Pension Bill, 1909; Customs Tariff Amendment Bill, 1909; Constitutional Alteration Bill, 1909; and the Commonwealth Public Service Bill, 1909. He continued to speak out on civil rights issues, defending army officers, Muslim camel drivers and boys forced to do military training. His rhetoric was at its best, at least to modern ears, when he spoke of the likely harm to children of Australian Kanaka parentage that would result from amendments to the Pacific Islands Labourers Act under which certain categories of Kanakas would be deported from Australia. ‘Goodness knows’, he cried, ‘they will have difficulties enough in front of them in a country that is so rampantly strong on the white Australia policy, without our making their case worse’. He continued: ‘I ask, in the name of good sense and humanity, what is to become of them? I do not think that we should be doing that which is right in the sight of either God or man if we adopted the present proposal’.

Neild stood unsuccessfully for re-election in 1910, and died at his home ‘Greycairn’ in Edgecliff Road, Woollahra, on 8 March 1911. His wife and the two children of his second marriage, Georgine and Reginald, survived him. Before he died he had been appointed honorary colonel of the St George’s English Rifles. The sometimes confused and always controversial senator received a military funeral before being buried, according to the rites of the Church of England, at Waverley Cemetery in Sydney. He was remembered fondly in newspaper obituaries. Even the Catholic Freeman’s Journal conceded that ‘he had occupied a unique place in Australian life, and that with all his imperfections many a man could be better spared from that life’.[7]

[1] Martha Rutledge, ‘Neild, John Cash’, ADB, vol. 10; Neildfile, ADB, ANU.

[2] Woollahra Municipal Council Minutes, 16 October 1885–19 January 1889, 17 June 1894, 24 July 1895–11 June 1901; NSWPD, 20 November 1885, pp. 122–132, 23 June 1886, pp. 2881–2909, 25 October 1888, pp. 131–132; Sir Alfred Stephen to Sir Henry Parkes, 19 March 1892, Parkes Papers, MSS A897, vol. 35, pp. 394–397, SLNSW; Sir Alfred Stephen, Australian Divorce Bills, Sydney, 1890; Martha Rutledge, Sir Alfred Stephen and Divorce Law Reform in New South Wales, 1886–1892, MA thesis, ANU, 1966; A. W. Martin, Henry Parkes: A Biography, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1980, p. 362.

[3] George Cockerill, Scribblers and Statesmen, J. R. Stevens, Melbourne, 1944, pp. 139–150; NSWPP, Report of the select committee on the Adelaide jubilee international exhibition, 1890; J. C. Neild, Correspondence, 1887–1890, Parkes Papers, MSS A897, SLNSW; J. C. Neild, Papers Relative to the Establishment of Old Age Pensions in Australia (typescript), MSS An 32, SLNSW; J. C. Neild, Report on Old Age Pensions . . . in England and . . . Europe, Sydney, 1898; NSWPD, 7 September 1899, p. 1308; George Houston Reid, My Reminiscences, Cassell, London, 1917, pp. 183–188; W. G. McMinn, George Reid, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1989, pp. 172–175.

[4] J. C. Neild, Songs ’neath the Southern Cross, Geo. Robertson & Co., 1896; Cosmos: An Illustrated Australian Magazine, 31 March 1896, vol. 2, no. 7, pp. 306–307; J. C. Neild, The Jesuits and Ultramontanism, George Murray, Sydney, 1892, The Irish Home Rule Bill, George Murray, Sydney, 1893; E. W. O’Sullivan, ‘From Colony to Commonwealth: Half a Century’s Reminiscences’ [1908], pp. 188–190, MSS B595, SLNSW; C. Wilcox, Australia’s Citizen Army 1889–1914, PhD thesis, ANU, 1993, pp. 90–91, 99–100;NSWPP, Report of the Court of Inquiry—7th Volunteer Infantry Regiment, 1900.

[5] Gavin Souter, Acts of Parliament, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1988, p. 40; G. S. Reid and Martyn Forrest, Australia’s Commonwealth Parliament 1901–1988, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1989, pp. 257–263; CPD, 9 August 1901, p. 3551, 16 August 1901, pp. 3842–3845, 28 May 1903, p. 183, 24 August 1905, pp. 1391–1410, 19 July 1907, pp. 763–766, 28 May 1903, pp. 191–192, 14 April 1904, pp. 942–947; James Jervis, The History of Woollahra, Halstead Press, Sydney, 1960, pp. 114, 179; Symon Papers, MS 1736, NLA; CPD, 4 December 1901, pp. 8259, 8278–8279, 5 December 1901, pp. 8283–8285, 8293–8294, 8302–8315, 6 December 1901, pp. 8388–8389, 8392; SMH, 21 November 1903, p. 11, 3 December 1903, pp. 7–8.

[6] J. C. Neild, ‘The Naval Defence of Australia’, Military Headquarters File 1902/2688, B168, NAA; CPD, 3 March 1904, pp. 46–62; SMH, 18 April 1904, p. 5; CPD, 20 April 1904, pp. 1106–1121; CPP, Report of the select committee on the case of Senator Lt.-Col. Neild, 1904; CPP, Report of the Senate committee of privileges on its history, practice and procedure, 1966-1996, 1996, p. 2; Letters between J. C. Neild and Sir Josiah Symon, 1901-02, Symon Papers, MS 1736, NLA; Military Headquarters File 1903/4672, B168, NAA; CPD, 14 December 1904, pp. 8390–8391; Carruthers Papers, MSS 1638/6; Neild Papers, MSS 2471, SLNSW; All About Australians, Sydney, 1 August 1904, p. 573.

[7] CPD, 22 June 1906, pp. 618, 637–639, 14 November 1907, p. 5980, 12 March 1908, pp. 8914–8917; 9 October 1906, p. 6273; Military Headquarters File 1906/1728, B168, NAA; Australian Magazine, (Sydney), vol. 12, 1 December 1909, p. 1027; Paddington: Its History, Trade and Industries 1860–1910,Paddington Municipal Council, Sydney, n.d., p. 109; Neild Papers, MSS 2471, SLNSW; SMH, 9 March 1911, p. 8; Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney), 15 March 1911, p. 22; Freeman’s Journal, (Sydney), 16 March 1911, p. 22.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 22-26.