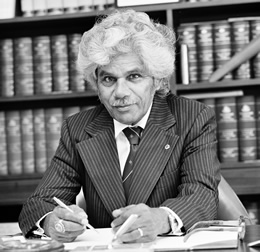

BONNER, Neville Thomas (1922–1999)

Senator for Queensland, 1971–83 (Liberal Party of Australia; Independent)

Neville Thomas Bonner, born ‘under a lone palm tree’ on 28 March 1922, at Ukerebagh Island, Tweed Heads, New South Wales, was a stockman and Aboriginal activist who believed it was in the best interest of his people to work for the Aboriginal cause within the existing political institutions of Australian white society. He was the first Indigenous Australian to sit in federal Parliament. [1]

Neville was the second son of Henry Kenneth Bonner, an English migrant, and his wife Julia, the daughter of Ida, née Sandy, and Roger Bell. In 1983 he spoke of his family background on his mother’s side:

My grandfather was a fully initiated member of the Jagara [Yuggera] tribe, whose tribal land was from the mouth of the Brisbane River [Queensland] to the foot of the Dividing Range. His name, Aboriginal name, was Jung Jung. But as a small boy he was … sort of captured I suppose out of the tribe … and given the name of Roger Bell … My grandmother [Ida Sandy] came from the Logan and Albert Rivers and she was a member of the Ugarapul tribe … My mother [Julia] was of course the result of that marriage between Ida Sandy and Roger Bell … [Julia] went down into New South Wales to a place called Murwillumbah, where she met and married Henry Kenneth Bonner.

When Julia was pregnant with Neville, Henry Bonner deserted the family leaving Julia destitute. Julia moved to an Aboriginal reserve on the mosquito-infested Ukerebagh Island, where ‘white men of very low standing’ would come with ‘grog’. She remained there for another five years or so, after which she took her two sons to the banks of the Richmond River, outside Lismore, living again in makeshift circumstances, under lantana bushes, but close to Ida and Roger. Ida, a devout Christian, whose faith Neville inherited, was fluent in English and exercised a strong influence on her grandson: ‘She was a disciplinarian, but she never smacked us’, preferring to explain rules of conduct.

Julia then lived with Frank Randell, an Aboriginal man, with whom she had three children, Eva, Frankie (who died as a child) and Jim. During this time Neville witnessed frequent acts of violence by Randell against his mother. The police inspector who employed Frank tried to have Henry, Neville and Eva enrolled in South Lismore School, an act thwarted by local parents, who threatened to remove their children if the newcomers remained. Julia died in July 1932.[2]

In an effort to educate her daughter’s children, Ida moved back to Queensland, where Aboriginals could attend local state schools and where Neville was enrolled in the third grade at Beaudesert State Rural School between February and December 1935. This was the only formal education he ever received. Six months after Ida’s death in June 1935, Bonner returned to New South Wales until his mother’s brother Jack came in search of the family, taking Neville back to Woorabinda Aboriginal settlement in Queensland. At Woorabinda Bonner learnt ‘the full meaning of being an Aborigine’, witnessing tribal ceremonies for the first time and learning his cultural heritage from the elders. Bonner moved around Queensland and northern New South Wales, jumping trains, working as a dairy hand, station hand and stockman and occasionally picking vegetables, clearing, ringbarking and fencing. At Cherbourg Aboriginal Settlement in 1940, he attempted, with other young Aboriginals, to enlist for service in World War II. They were rejected. No official explanation was provided, but army enlistment by Aboriginals was not encouraged at this time.[3]

On 14 June 1943 he married Mona Banfield, a domestic servant and station cook, in the Catholic Church at the Aboriginal settlement of Palm Island. The couple lived in Hughenden, where Neville found itinerant work and Mona was engaged as a domestic servant. One week Neville returned home to find his wife gone. In response to a racial insult Mona had slapped the face of her employer. Without trial and without informing Neville, the authorities had despatched Mona back to Palm Island for one year under supervision. Their first son, Patrick, was born there. Mona rejoined Neville on the mainland, where he had found work on an isolated cattle station. After Patrick became seriously ill, Mona believed that a return to Palm Island would be best for family life. Bonner reluctantly agreed. They would remain on Palm Island from 1945 until 1960, having four more sons and fostering three other children.

Though Neville was one of the few men allowed to take seasonal work on the mainland, as a canecutter around Ingham, it was on Palm Island that he was appointed a native policeman, advancing to the position of assistant works overseer with responsibility for about 300 people. Bonner was active in the Palm Island Social and Welfare Association of which he was a foundation member. On first arriving at Palm Island, Bonner had, by his own account, been ‘very rebellious’, but in order to get things done he became ‘quite expert’ in negotiating with the white authorities on the island. In 1957, convinced that discrimination could not be met by confrontation, he assisted striking Palm Island workers to draft a letter of grievance to the Director of Native Affairs in Brisbane, although some of the strikers physically attacked him for his association with the authorities.

In 1960 Bonner attracted the attention of the Queensland Director of Native Affairs, Con O’Leary, who invited him to work in Brisbane as a curator of exhibitions on Aboriginal art and artefacts. He attended, with O’Leary, a conference on Aboriginal affairs in Cairns. O’Leary then offered Bonner a position as the first Aboriginal departmental officer, with responsibility for the art section at Cherbourg, on the condition that Bonner and his family were segregated from the rest of the Aboriginals in the community. Refusing to divorce himself from his people, Bonner turned down the position. Annoyed at this, O’Leary declared Bonner could no longer remain on Palm Island. Leaving the island and for a time his family, in September 1960 Bonner moved to Mount Crosby, outside Brisbane, where he managed a dairy farm, later working as a labourer for the Brisbane City Council. In 1966 he established his own business manufacturing boomerangs, trading under the name of Bonnerang. The costs involved in finding the right wood made the business unviable after about a year. From 1968 to 1971 Bonner worked as a carpenter for Moreton Shire Council.[4]

By the early 1960s, he had developed a taste for politics. In Ipswich Bonner joined a group known as the Coloured Welfare Council, which merged with the One People of Australia League (OPAL), formed in 1961 to channel Queensland Government assistance to areas of Aboriginal need. OPAL’s ultimate goal was ‘to weld the coloured and white citizens of Australia into one people’. In 1965 he was elected to OPAL’s state committee, serving as the league’s president from 1968 to 1974. It was at OPAL that Bonner met Heather Ray Ryan, née Trotter, her politically minded daughter, Robyn, and son-in-law Noel Kunde. Mona died on 2 September 1969, and on 29 July 1972 Bonner married Heather at Opal House, Eight Mile Plains, Brisbane.

Robyn and Noel were members of the Liberal Party and invited Bonner to meetings at Ipswich. Bonner, as a ‘working man’, had always seen himself as a Labor voter and remarked ‘you’d have to be joking’, but went along and was impressed with party documents, particularly a statement of Liberal beliefs by R. G. Menzies. During the campaign for the May 1967 referendum, which included a successful proposal to give the Commonwealth the power to make laws for Aboriginal people, Bonner handed out how-to-vote cards for the Liberal Party. He was challenged by the local Labor MHR, Bill Hayden, who argued that the ALP did more for Aboriginals than the Liberals. Bonner, annoyed that Labor should presume the automatic support of Aboriginal people, decided to join the Liberal Party, becoming a member of the One Mile branch in August 1967.[5]

By June 1968 Bonner was a branch delegate to the Queensland Liberal Party convention and, by 1969, a member of the party’s state executive. On 2 March 1970 Bonner was nominated by the Queensland Liberal Party for preselection for the half-Senate election later that year. Placed third on a joint Liberal–Country Party ticket, he was unsuccessful. In 1971 the party nominated him again, this time for the casual vacancy caused by the resignation of Senator Annabelle Rankin. There was speculation that the vacancy would be filled by Eric Robinson, president of the Queensland Liberal Party (Robinson, later an MHR and a minister in the Fraser Government, would become a close and crucial political ally of Bonner). Bonner believed that the vacancy was rightly his and made a strong public statement to that effect, thereby making it difficult for the party to select another candidate without embarrassment. On 11 June the Queensland Parliament elected Bonner to the casual vacancy. It was a historic appointment.

He was sworn in the Senate on 17 August. In his first speech on 8 September, he declared that he would play ‘the role which my State of Queensland, my race, my background, my political beliefs, my knowledge of men and circumstances dictate’. That he could balance his loyalty to his state and the party that had brought him to Canberra with his undoubted commitment to and love of his people was no mean achievement. Refusing to let a deprived upbringing become a cause of complaint, and with a strong belief in liberal democracy, Bonner was not shy of using political methods to further the causes he espoused. His mild manner concealed a robust personality.[6]

Bonner described himself as having ‘an all-consuming burning desire to help my own people’. He wished to see Aboriginal Australians retain their cultural identity, while acquiring the economic, educational and social opportunities that white Australians took for granted. In his first speech he appealed for greater efforts from both state and Commonwealth governments in the provision of pre-school education for Aboriginals. But on policy issues, while Aboriginal problems were undoubtedly of prime importance to him, they were not of sole importance. Years later, he emphasised that he had tried in his political career ‘to serve all people’. Among the issues he raised in the Senate were national symbolism (the flag and the anthem), moral degeneration, technological opportunities, East Timor, imperial versus metric measures, and social security entitlements.

He did not always vote with the Liberal Party, crossing the floor of the Senate on some thirty-four occasions. He had, he declared, ‘a conscience, and political parties don’t need people with a conscience. They want bottoms on seats—and hands in the air at the right time’. In late 1975 he was greatly troubled by his party’s decision to block supply to the Whitlam Government. On 27 April 1976, he joined a small group of Liberals in voting against clauses in the Social Services Amendment Bill that would have removed benefits to pensioners. In February 1977 he joined those Liberal rebels who protested against the Constitution Alteration (Simultaneous Elections) Bill, which they considered a threat to the power and independence of the Senate. In May 1981 he was one of four Liberals whose efforts resulted in amendments to the Freedom of Information Bill, one of which provided for the scrutiny of documents used by agencies to interpret legislation and procedural rules. In June 1981 he was the lone Government voice opposing the Petroleum (Submerged Lands—Miscellaneous Amendments) Bill due to his concern about drilling in the Great Barrier Reef. In November 1981 he crossed the floor with six other Liberals, supporting a motion for the establishment of the Senate Standing Committee on the Scrutiny of Bills, whose purpose was, and remains, to scrutinise bills for breaches of civil liberties.[7]

Bonner was never slow to proclaim his Aboriginality. Being a moderate did not make him a cringer before a white population. In September 1972 he spoke on a motion to disallow trespass on Commonwealth lands, which had been brought in by the McMahon Government in what proved to be a futile attempt to remove the ‘Tent Embassy’ set up in front of Parliament House. While he sympathised with the motives of those who had established the ‘embassy’, who, he said, ‘were demonstrating against all the things that have happened over the years—the shootings, the killings, the taking of the land’, Bonner urged the protesters to obey the law. He disagreed with the term ‘embassy’ because of its implication that Aboriginal people were foreigners. The suggestion that the tents on the lawns were unsightly caused him to ask: ‘Is there anything more unsightly than to see the Aboriginal people in a place such as Camooweal’, pointing out that there they lived under sheets of galvanised iron, where the temperature reached 110 degrees Fahrenheit. In 1974 Bonner moved a motion that acknowledged Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as the original owners of the continent and urged the Australian Government to pay compensation for the dispossession of the land.[8]

His relationship with the Queensland Coalition Government, led by Joh Bjelke-Petersen, gradually deteriorated. During the first few months of his Senate career, he was prepared to support the Queensland Government over its declaration of a state of emergency for the tour by the South African rugby union team. He also defended it against stinging criticisms of Queensland’s administration of Palm Island made by the ALP Caucus committee on Aboriginal affairs. Mutual disenchantment followed. In 1976 Bonner told the Senate that the people of Aurukun in Queensland had not been properly consulted about bauxite mining proposals on the land which they owned under Queensland’s Aurukun Associates Agreement Act 1975, and he praised the Queensland Ombudsman’s critical report on the Queensland Government’s handling of the interests of the Aurukun people. In 1982 he objected to the Premier’s pejorative use of the terms ‘radicals’ and ‘activists’ to characterise, respectively, supporters of Aboriginal land rights and the personnel of the National Eye Health and Trachoma program. As he proudly pointed out, his own life had been one of ‘activism’.

In the face of a centralist government in Canberra, Aboriginal and state issues merged in 1974. When, on 27 November, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (Queensland Discriminatory Laws) Bill, introduced by the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs in the Whitlam Government, Senator Cavanagh, came before the Senate, Bonner urged that the bill be deferred until ‘the Aboriginal people in Queensland are consulted’. With all Liberal senators, he supported an amendment by Senator Peter Rae that would allow Aboriginal communities to restrict who could visit their lands. It was unsuccessful. Earlier Bonner had warned that if the Commonwealth wanted to ‘go into Queensland and take control of Aborigines … they will do so over my dead body’. After various changes, including an amendment by Senator Cavanagh, the bill finally passed both houses in May 1975. Bonner would compliment Cavanagh for his work on this legislation.

He also praised the Fraser Government for implementing some improvements in Aboriginal land policy. When the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 was passed, Bonner offered to defy the Opposition’s criticism by dancing a corroboree in the Senate chamber, though he regarded the Government’s subsequent acceptance of the (newly self-governing) Northern Territory’s ‘complementary legislation’ as an abdication of the powers given to the Commonwealth at the 1967 referendum. In March 1976 Bonner was appointed chair of the Select Committee on Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders, which presented its final report on sacred sites in August 1976.[9]

In August 1977 Bonner presented his report as chairman of the Joint Select Committee on Aboriginal Land Rights in the Northern Territory. The committee found that Northern Territory provisions regarding entry onto Aboriginal land and for the protection of sacred sites were inadequate. It also recommended that Aboriginal communities enjoy the right to exclusive use of certain areas of the seas adjacent to their land, a right eventually confirmed by the High Court in 2008. By April 1978, the Fraser Government, prompted by the Queensland Government’s announcement in March that it would take over the Aurukun and Mornington Island Reserves, had passed the Commonwealth’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (Queensland Reserves and Communities Self-Management) Act. This led to an immediate announcement by the Queensland Government that it would turn the reserves into local government areas, thus placing them outside the jurisdiction of the Commonwealth. Bonner then moved that the Senate’s Standing Committee on Constitutional and Legal Affairs consider the constitutional basis of the Commonwealth’s intervention. The committee presented its report in November, outlining ways in which the Commonwealth might proceed, but the Fraser Government took no further action. The following year, ALP senators Cavanagh and Keeffe accused Bonner of selling out his own people. Bonner retorted that Cavanagh looked at the Aboriginal question ‘through the eyes of a white man’. At other times, Bonner and the two ALP senators had worked together, but this did not rule out vigorous engagement in the usual give and take across the chamber. During these exchanges Bonner expressed his belief that ‘the aspirations of the indigenous people of this country’ could only be achieved by ‘negotiation’, not ‘confrontation’.[10]

Bonner was long troubled by the task of reconciling Indigenous rights and cooperative federalism. When debating the establishment of the Human Rights Commission in 1979, he lamented that state laws were beyond the Commonwealth’s proposed powers, crossing the floor to support three amendments, all unsuccessful. In September 1981 he again urged a more cooperative approach when he supported an amendment by Senator Alan Missen requesting more information from the Queensland Government during the debate on the Queensland Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders (Self-Management and Land Rights) legislation, a private senator’s bill, introduced by Susan Ryan, Labor’s shadow minister for Aboriginal affairs. Two years later, and no longer a senator, he warned that a treaty with Aboriginal people was jeopardised by the strong temptation, under federalism, to let the states determine Australian approaches to race relations. In 1979 and 1980 he was allowed, by special motion, to take the Aboriginal Development Commission Bill, and a replacement bill, through their stages in the Senate, in effect a tribute by the Government to his standing in Aboriginal affairs. The second bill gained assent on 16 May 1980.[11]

With assistance from Eric Robinson, Bonner survived a testing preselection contest in 1980. Robinson died early in 1981 and, prior to the 1983 election, which brought the ALP Government of Bob Hawke into power, Bonner was relegated from first to third place on the Senate ticket. His advocacy of Indigenous rights and his insistence on raising environmental considerations (such as mining the Great Barrier Reef) had alienated too many powerful figures in the Liberal and National parties in Queensland, not least the Premier of Queensland himself. Deeply disappointed and feeling betrayed by party members he had considered friends, he resigned from the Liberal Party in February 1983 to stand as an independent, and lost. Fifteen years later, he was made a life member of the Liberal Party.[12]

Bonner left the Senate at the end of his term amid a plethora of fine phrases, most of which doubtless were sincere. His gentle manner coupled with determination had earned respect. His concern for relations between police and Aboriginals is apparent in his 1976 private senator’s bill, the Aborigines and Islanders (Admissibility of Confessions) Bill. Describing it as ‘momentous’, he must have known (as did the major parties who gave it no support) that, as the bill sought to regulate questioning of Aboriginal people by state police, it could hardly be passed by the Commonwealth. Its value lay in alerting politicians to practices that led to the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. Similarly his 1973 critique of the National Aboriginal Consultative Committee may be considered as part of the movement towards the establishment of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission.[13]

In January 1979 Bonner was made Australian of the Year and, in 1984, he was appointed an Officer of the Order of Australia. From 1983 to 1991 he was a member of the board of the Australian Broadcasting Commission; in 1993 he was awarded an honorary doctorate by Griffith University in Queensland; from 1995 to 1996 he chaired a government review of the Aboriginal Lands Trust in Western Australia. In 1997 Bonner was chair of Queensland’s Indigenous Advisory Council, and was invited by the President of the Children’s Court in Queensland to conduct court proceedings at the Aboriginal community in Cherbourg. In February 1998 he was an elected monarchist delegate to the Constitutional Convention held in Canberra. Bonner regarded the republic debate as an unnecessary and a divisive distraction from more pressing social issues. In the same year, the Premier of Queensland, Peter Beattie, invited him to address the opening of the 49th Queensland Parliament. He wrote two publications for World Vision, of which he was a patron: Equal World Equal Share, in 1977, and For the Love of Children, c. 1982.[14]

Neville Bonner died on 5 February 1999, at the Ipswich Hospice. He was accorded a state funeral at St Stephen’s Presbyterian Church, Ipswich, and was buried in Warrill Park Lawn Cemetery. The service was broadcast on ABC television. Heather survived him, as did four of the five children of his first marriage and two foster daughters. Heather’s three children also survived him. The Queensland federal electorate of Bonner is named after him.

Bonner was sometimes accused of being too sympathetic to white views and was labelled a ‘tame cat’ or ‘Uncle Tom’. A proud man of notably independent mind, Bonner was hurt by such language, but understood the frustrations of those who criticised him in such terms, and had said: ‘I wasn’t selling them out, but they didn’t understand what I was doing’. He was acutely conscious of the burden of expectations placed on him as the first Indigenous person to enter federal Parliament: ‘My whole political life was under scrutiny. The way I walked, the way I talked … everything I did was being judged, and the whole race was being judged on it’. He was determined to establish himself as a contributor to Parliament on a broad range of matters and to consolidate his position as an effective and, when necessary, forceful Aboriginal voice for as long as possible.

His commitment came at a cost. Years later, Bonner spoke of the loneliness felt by many federal politicians, though in his case it must have had a particular sting. ‘It was’, he said,

worse than being out droving … I was treated like an equal on the floor of the chamber, neither giving nor asking quarter, but there were hours just sitting in my office and I went home alone to my unit at night. There was never one night when anyone said, ‘Hey, let’s go out tonight’.[15]

[1] Ann Turner (ed.), Black Power in Australia, Heinemann Educational Australia, South Yarra, Vic., 1975, introductory page; CPD, 21 Nov. 1973, p. 2017, 12 Mar. 1974, p. 197.

[2] Neville Thomas Bonner, Transcript of oral history interview with Pat Shaw, 1983–85, POHP, TRC 4900/64, NLA, pp. 1:1–3; Angela Burger, Neville Bonner: A Biography, Macmillan, South Melbourne, 1979, pp. 1–12; Robin Hughes, Australian Lives: Stories of Twentieth Century Australians, A & R, Pymble, NSW, 1996, pp. 77, 80–1.

[3] Bonner, Transcript, p. 1:4; Beaudesert State School, Admissions register, 1927–36, SRS 1747/1/12, QSA; Burger, Neville Bonner, pp. 13–20.

[4] Bonner, Transcript, pp. 1:5–8; Burger, Neville Bonner, pp. 22–38, 47–8; Hughes, Australian Lives, p. 85; Neville Thomas Bonner, Employment card, Brisbane City Council Archives.

[5] Hughes, Australian Lives, pp. 89–91; Bonner, Transcript, pp. 1:8–10; OPAL, Annual reports, 1966–75; Burger, Neville Bonner, pp. 37–57; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 29 July 1972, p. 8.

[6] Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 11 June 1968, p. 3; Liberal Party of Australia, Qld division, 27th annual convention, 1970; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 2 Mar. 1970, p. 3, 3 Mar. 1970, p. 3, 25 May 1971, p. 1; Burger, Neville Bonner, pp. 73–4, 100; Bonner, Transcript, p. 1:12; QPD, 11 June 1971, pp. 3742–53; CPD, 8 Sept. 1971, p. 553.

[7] Hughes, Australian Lives, pp. 98, 106; CPD, 8 Sept. 1971, p. 555; Anne Deveson, Coming of Age: Twenty–One Interviews About Growing Older, Scribe Publications, Newham, Vic., 1994, p. 205; CPD, 24 Oct. 1979, p. 1682, 11 May 1978, p. 1638, 7 Apr. 1976, p. 1173, 31 Mar. 1977, pp. 733–7, 6 June 1979, p. 2719, 2 June 1976, pp. 2266–7; Deirdre McKeown, Rob Lundie and Greg Baker, ‘Crossing the Floor in the Federal Parliament 1950–August 2004’, Research Note, CPL, no. 11, 2005–6; Paul Kelly, November 1975: The Inside Story of Australia’s Greatest Political Crisis, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards, NSW, 1995, pp. 237–40; CPD, 27 Apr. 1976, pp. 1283, 1287; Senate, Journals, 22 Feb. 1977, p. 578, 25 Feb. 1977, pp. 592–6; CT, 26 Feb. 1977, p. 20; Senate, Journals, 7 May 1981, pp. 243, 245; CT, 8 May 1981, p. 6; CPD, 2 June 1981, pp. 2461–3; Senate, Journals, 19 Nov. 1981, p. 677.

[8] CPD, 20 Sept. 1972, pp. 1030–3, 14 Nov. 1974, p. 2428, 19 Sept. 1974, p. 1267, 20 Feb. 1975, p. 367.

[9] Burger, Neville Bonner, pp. 83–4; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 5 July 1971, p. 3, 2 June 1971, p. 16; CPD, 25 Feb. 1976, pp. 249–52; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 26 Jan. 1976, p. 3; CPD, 8 Apr. 1976, pp. 1227–8, 24 Sept. 1981, p. 1062, 21 Apr. 1982, pp. 1412–14, 5 Dec. 1974, pp. 3203–6, 3211, 29 Oct. 1974, p. 2097; Senate, Journals, 29 May 1975, p. 723; CPD, 5 June 1975, pp. 2368–9, 9 Dec. 1976, p. 2915, 17 Aug. 1977, p. 148.

[10] CPP, 351/1977; SMH, 8 Mar. 1976, p. 8; CPD, 6 Apr. 1978, pp. 902, 936–40, 11 Apr. 1978, p. 1103, 23 Nov. 1978, p. 2455, 5 Apr. 1979, p. 1427.

[11] CPD, 12 June 1975, p. 2665, 20 Aug. 1980, p. 142, 13 Nov. 1979, pp. 2186–9; Senate, Journals, 13 Nov. 1979, p. 1035, 14 Nov. 1979, p. 1042, 19 Nov. 1979, p. 1071; CPD, 24 Sept. 1981, pp. 1060–4; Aboriginal Treaty News (Canb.), Mar.–June 1983, p. 2; WA (Perth), 10 Dec. 1979, p. 7; CPD, 21 Nov. 1979, pp. 2629–32, 17 Apr. 1980, pp. 1565–8.

[12] Age (Melb.), 10 Feb. 1983, pp. 5, 9; CPD, 2 June 1981, pp. 2461–3; Scott Bennett, Aborigines and Political Power, Allen & Unwin, North Sydney, 1989, pp. 121, 125; CT, 13 Feb. 1983, p. 1; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 16 Mar. 1998, p. 2.

[13] CPD, 3 May 1983, pp. 131–42, 15 Sept. 1976, pp. 695–8, 26 Oct. 1978, pp. 1658–61, 5 Mar. 1981, pp. 367–70; Aboriginal Law Bulletin (Kensington), Aug. 1981, p. 5; CPD, 21 Nov. 1973, pp. 2016–19.

[14] CT, 26 Jan. 1979, p. 1; ABC, Annual report, 1990–91; Griffith University, Annual report, 1993, p. 21; Aboriginal Lands Trust Review Team, The Review of the Aboriginal Lands Trust, Aboriginal Affairs Department, Perth, 1996; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 14 Jan. 1997, p. 3; Children’s Court of Queensland, Annual report, 1997–98; Report of the Constitutional Convention, 4 Feb. 1998, pp. 261–3; QPD, 29 July 1998, p. 1343; Age (Melb.), 6 Feb. 1999, p. 8; Notable Australians: The Pictorial Who’s Who, Prestige Publishing Division, Paul Hamlyn, Sydney, 1978, p. 149; Neville Bonner, Equal World, Equal Share, World Vision [1977]; Neville Bonner, For the Love of Children, World Vision [1982?].

[15] Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 10 Feb. 1999, pp. 8, 26; Hughes, Australian Lives, pp. 94, 101; Mercury (Hob.), 8 June 1996, p. 44.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 3, 1962-1983, University of New South Wales Press Ltd, Sydney, 2010, pp. 356-364.