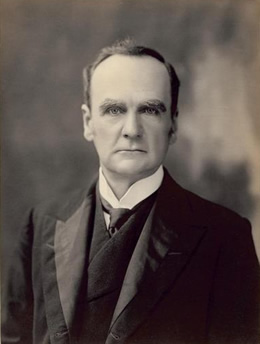

MACKELLAR, Charles Kinnaird (1844–1926)

Senator for New South Wales, 1903 (Protectionist)

Described affectionately as ‘the children’s friend’, Sir Charles Kinnaird Mackellar was a practical philanthropist whose life work involved the care of the ‘helpless, homeless and friendless’. A physician, businessman and social reformer, Mackellar was born in Sydney on 5 December 1844, the son of Frederick Mackellar, a distinguished medical practitioner, and Isabella McGarvie, née Robertson.

After completing his education at Sydney Grammar School, Mackellar travelled to Scotland to study medicine at his father’s Alma Mater, the University of Glasgow. He graduated in 1871 and worked as a house surgeon for six months in the Royal Infirmary, Glasgow, before returning to Australia where he started a medical practice in College Street, Sydney. Later, he also worked as an honorary surgeon in the Sydney Infirmary and Dispensary. On 9 August 1877, he married Marion Buckland at St Paul’s Church of England, Sydney.

In January 1882, Mackellar was appointed to the Board of Health becoming President the following year. He was soon to become medical adviser to the Government, health officer and emigration officer for Port Jackson, chairman of the Immigration Board, and a member of the board of official visitors to the Gladesville and Parramatta Asylum Hospitals. He was a member of the Pharmacy Board, the Medical Board of New South Wales and the State Children Relief Board and a director of Sydney Hospital and the Prince Alfred Hospital. [1]

In 1883, Mackellar delivered an influential paper on federal quarantine to the Royal Society of New South Wales. The paper underlined the need for the colonies to agree on common quarantine regulations, and proposed quarantine stations in northern and southern Australia. The following year, Mackellar was the New South Wales delegate at an intercolonial conference, which emphasised the importance of a uniform system of quarantine.[2]

Over the years, Mackellar had established a reputation as a leading member of his profession and one who rendered ‘distinguished and self-denying service to the community’. Thus his appointment to the Legislative Council in August 1885 received public applause. In 1886, he was Vice-President of the Executive Council and representative of the Government in the Legislative Council, and from December 1886 to January 1887, during the short-lived Jennings Government, was Secretary for Mines.

In Parliament and in the community, Mackellar pushed for change to social legislation. He told one public gathering that he wanted to enlist their ‘sympathy and earnest co-operation . . . in securing the enactment of reform in certain laws relating to the social conditions of the people, and especially children’. In keeping with this commitment,he was responsible for the introduction into the New South Wales Parliament of such legislation as the Crimes (Girls’ Protection) Bills (1903, 1905), and the Infant Protection Bill (1902, 1903); the latter became law in 1904.[3]

On 13 August 1903, Mackellar was appointed president of the royal commission on the decline of the birth rate in New South Wales. He had already served on a number of committees of inquiry, including one on the management of the Sydney Hospital (1883) and another on the registration of births, deaths and marriages (1886). The commission had barely started before Mackellar agreed to the suggestion made by Sir John See, the New South Wales Premier, that he should stand as a candidate for the Senate casual vacancy created by the resignation of Senator Richard O’Connor.

On 8 October 1903, in accordance with section 15 of the Australian Constitution, the two Houses of the New South Wales Parliament met to choose a senator. This was the first occasion in New South Wales for such a joint sitting. The proceedings followed those established in Victoria in January 1903. The meeting generated debate as to whether Parliament ought to return a Protectionist to replace the one who had resigned, or, whether each member, as a representative of a constituency, ought to vote according to the prevailing political views of his constituents. Although Mackellar insisted that he was a non-party man, nonetheless he was the endorsed candidate of a Protectionist government. When Joseph Carruthers, the Leader of the Opposition, nominated John Proctor Gray, a straight-out Free Trader, the vote became political. The decision to elect the replacement senator by secret ballot effectively released members from making a public commitment on the matter, and Mackellar was elected to fill the vacancy.

He was sworn as a senator on 14 October 1903. Only five sitting days remained in the session, and the anticipated prorogation of Parliament overshadowed business in the chamber. Nevertheless, a lively debate on the site of the federal capital ensued and, though Mackellar did not engage in any debate, he did vote consistently with his New South Wales colleagues on the Seat of Government Bill.[4]

Mackellar did not contest the December federal election. Perhaps he concluded that he could achieve more outside the Federal Parliament than in it. Without missing a step, he returned to public duties in New South Wales. Although he was reappointed to the Legislative Council on 26 November, his main interest lay in the birth rate royal commission. Its scope had been extended on 30 October to include an investigation into the mortality of infants in New South Wales. Under Mackellar’s firm direction, the commission held forty meetings and handed down a report regarded by the medical fraternity as a ‘masterpiece of exhaustive examination and investigation’. Uncompromising in its approach, the report concluded that the serious decline in the birth rate since 1889 had been due mainly to contraceptive practices and induced miscarriages. It attributed the use of birth control to a selfish desire for personal comfort. The report also addressed the alleviation of infant mortality, including the instruction of mothers and young girls in the care of infants.

Though disappointed by the slow pace of social reform, Mackellar continued to agitate for change. In 1907, he expressed regret at the lack of legislation on the supervision of ‘illegitimacy and the serious disabilities connected with it’. One of his guiding principles as president of the State Children Relief Board (1903–14) was that institutions ‘must be adapted to the needs of the children, and not vice versa’.[5]

On 1 January 1912, he was created a KB, in recognition of his philanthropic work. Four days later, he was appointed to inquire into the treatment of delinquent and neglected children in Great Britain, Europe and America. For twelve months, Mackellar travelled extensively, visiting reformatories, industrial schools, training-ships, remand homes and children’s courts. The sole member of the inquiry, he produced a raft of recommendations. In particular, Mackellar wanted uniform laws for neglected children and compulsory registration and inspection of children’s institutions.

In 1916, Mackellar was appointed KCMG in recognition of his community work. Involved also in the commercial world, he was president of the Bank of New South Wales for more than twenty years and a director of a number of companies. By 1923, he stepped back from public life and in 1925, due to his non-attendance in Parliament, forfeited his seat in the Legislative Council. He died on 14 July 1926 and, following a service at his home in Woollahra, was buried in the Church of England section of Waverley Cemetery. His wife and daughter, Dorothea (the prominent poet), and two sons, Eric and Malcolm, survived him. A third son, Keith Kinnaird, had been killed in action in the Boer War. Colleagues remembered Mackellar as ‘a staunch friend whose strong hand was ever extended to help and to guide’.[6]

[1] Ann M. Mitchell, ‘Mackellar, Sir Charles Kinnaird’, ADB, vol. 10; SMH, 28 November 1914, p. 9; Mackellar Correspondence, 1871–1922, MSS 1959, SLNSW.

[2] J. H. L. Cumpston, The Health of the People: A Study in Federalism, Roebuck Society Publication no. 19, Canberra, 1978, pp. 9–12.

[3] SMH, 1 September 1885, p. 7; C. K. Mackellar, State Children Bill and Infants’ Protection Bill: Address to the Women’s Progressive Association, 20 April 1903, Sydney, 1903, p. 3; NSWPD, 8 July 1903, p. 539, 14 June 1905, p. 56, 29 June 1905, p. 477, 3 December 1902, p. 4991, 22 July 1903, p. 874.

[4] NSWPD, 8 October 1903, pp. 3188, 3189–3210; CPD, 15 October 1903, pp. 6179, 6188-6189, 6197, 6200, 21 October 1903, p. 6346.

[5] Australasian Medical Gazette (Sydney), vol. 23, 21 March 1904, p. 120; NSWPP, Report of the royal commission on the decline of the birth-rate and on the mortality of infants in New South Wales, 1904; Neville Hicks, ‘This Sin and Scandal’: Australia’s Population Debate 1891–1911, ANU Press, Canberra, 1978, pp. 1–18; Among Mackellar’s publications are The Child, the Law, and the State, Government Printer, Sydney, 1907, The State Children: An Open Letter to The Honorable A. G. F. James, M. L. A., Minister for Education, Sydney, 1917, The Mother, the Baby, and the State: An Open Letter to The Honorable J. D. Fitzgerald, M. L. C., Minister for Public Health, Sydney, 1917 and C. K. Mackellar and D. A. Welsh, Mental Deficiency: Medico-Sociological Study of Feeble-Mindedness, Sydney, 1917.

[6] NSWPP, The treatment of neglected and delinquent children in Great Britain, Europe, and America with recommendations as to amendment of administration and law in New South Wales, 1913; Stephen Garton, ‘Sir Charles Mackellar: Psychiatry, Eugenics and Child Welfare in New South Wales 1900–1914’, Historical Studies, vol. 22, no. 86, April 1986, pp. 21–35; SMH, 12 October 1912, p. 5, 28 November 1914, p. 9, 3 January 1916, p. 6, 15 July 1926, p. 12; Medical Journal of Australia, vol. 11, 7 August 1926, pp. 196–198; R. L. Wallace, The Australians at the Boer War, AWM and AGPS, Canberra, 1976, pp. 219–220.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 39-41.