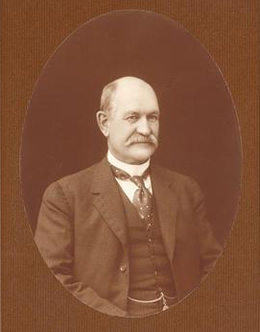

OAKES, Charles William (1861–1928)

Senator for New South Wales, 1913–14 (Liberal Party)

Charles William Oakes, jeweller, was a senator for one year and a New South Wales parliamentarian for more than twenty. He was born at Wagga Wagga, New South Wales, on 30 November 1861, the son of James Richard Oakes, a storekeeper from Lancashire, and his wife, Agnes Jane, née Revelle. In 1870, the family moved to Sydney, where Charles was educated at Paddington Superior Public School. He was apprenticed to a jeweller and later successfully established his own business in Oxford Street, Paddington. A shrewd businessman, he was able to retire from active involvement in his business in 1911.

Oakes developed an early interest in political and community service. A member of the Paddington and Woollahra Literary and Debating Society, he also belonged to the first Union Parliament of Debating Societies. A committed free trader, he joined the fledgling Labor Party in 1891 but, refusing to sign the Party’s solidarity pledge, resigned in 1894. From 1898 to 1905, he was an alderman on the Paddington Municipal Council, declining the mayoral nomination in 1904. A member of the Liberal and Reform Association, in 1901 he campaigned as a Liberal and was elected to the New South Wales Legislative Assembly as the Member for Paddington. From 1907 to 1910, he was a member of the Executive Council and Honorary Minister (that is, minister without portfolio) in the Wade Government—largely assisting the Premier. He was defeated at the 1910 election.[1]

In 1913, Oakes was elected as a senator for New South Wales, representing the Liberal Party. He found himself in a deadlocked Parliament. Cook’s Liberal Government had a majority in the House, but with a Labor-controlled Senate. Oakes proved to be a fierce critic of this situation. He maintained that Labor was betraying the principles of the Constitution by voting as a party in the Senate when the Senate was constitutionally a States House. He remained a firm advocate of states’ rights, arguing that the Commonwealth Bank should not impinge on the activities of state banks. He vigorously engaged in a number of jousts with Labor senators, particularly Robert Storrie Guthrie about union preference, postal voting, government centralisation, and trusts and combines. He accused Labor senators of being ‘hypocrites’ for criticising trusts and combines while at the same time advocating trade union preference and closed shops. Trusts, maintained Oakes, were efficient and able to sell goods more cheaply, thereby benefiting all Australians.[2]

Oakes’ sense of public morality and fair play were reflected in his membership of Senate committees including that of the select committee on the general elections, which investigated widespread claims of corruption in the conduct of the election. Newspapers detailed charges of roll-stuffing, double voting, impersonation and suppression of ballot papers, but the select committee found no evidence to support these claims. In November 1913, Oakes showed some interest in the proceedings of a committee of which he himself did not wish to be a member. A Senate select committee was investigating why Henry Chinn, an engineer on the transcontinental railway, previously cleared of incompetence by a royal commission, had not been reinstated by the Cook Government. Oakes was successful in having a motion passed in the Senate, which required the committee to examine Chinn’s qualifications on the basis that the public had ‘a right to know the full facts of the case’.

With the Government still unable to get its legislation through the Senate, Oakes argued the case for a double dissolution, so that the deadlock could be resolved. In June 1914, following extensive Senate amendments to the Postal Voting Restoration Bill and rejection of the Government Preference Prohibition Bill, the Prime Minister sought and subsequently obtained a double dissolution. Ironically, Oakes was defeated at the subsequent September election, his Senate career thereby shortened by five years.[3]

After a brief spell from public life, Oakes returned to state politics. In 1917, as a Nationalist, he was elected as the Member for Waverley, and in 1920 and 1922 for Eastern Suburbs as a Nationalist and Nationalist Progressive, respectively. He was deputy leader of the Nationalist Party from 1920 to 1925, and a minister in the Holman and Fuller governments, most notably as Colonial Secretary and Minister for Public Health (1922–25). For six months in 1923, he was acting Premier. An able administrator, he used his wide contacts to smooth relations between the various factions in non-Labor politics in New South Wales. At the expiration of his term in 1925, he did not seek re-election, but was appointedto the Legislative Council, where he remained until his death in 1928.

Oakes was a man of wide interests and connections. As a young man he had excelled at sport, particularly cricket, rugby and cycling. Later, he became president of the New South Wales Rugby Union, president of the Cricket Association, chairman of trustees of the Sydney Cricket Ground and vice-president of the Surf Life Saving Institution. He was an active participant in sectarian politics, advancing the cause of Protestantism through such organisations as the Oddfellows, the Ulster Association, the Loyal Orange Institution and the Australian Protestant Defence Association. He was a Freemason and a member of the Australian Natives’ Association. Oakes was part of the organising committee for the visit of the Prince of Wales in 1920 and in 1922 was appointed CMG.

On 1 September 1885, he married Elizabeth Gregory, niece of the cricketer, David Gregory. Oakes died on 3 July 1928 at his home in Bellevue Hill and was buried in the Anglican section of Waverley Cemetery. His wife survived him, as did Roy and Muriel—two of four children. Widely liked for his easygoing manner, Oakes was described as a ‘loyal and efficient member of his own party . . . [and] most of all a faithful servant of the whole community’.[4]

[1] Mark Lyons, ‘Oakes, Charles William’, ADB, vol. 11; SMH, 8 July 1901, pp. 7–8; Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney), 4 March 1908, p. 37;The Cyclopedia of New South Wales, McCarron, Stewart & Co., Sydney 1907, p. 97;Fighting Line (Sydney), 19 April 1913, p. 21; Information from Woollahra Municipal Council, NSW; Paddington: Its History, Trade and Industries 1860–1900, Paddington Municipal Council, Sydney, n.d.

[2] CPD, 20 November 1913, p. 3338.

[3] CPD, 15 April 1914, pp. 12–20, 2 October 1913, p. 1726, 3 June 1914, pp. 1722–1731; Senate, Journals, 5 November 1913; CPD, 5 November 1913, pp. 2862–2866.

[4] SMH, 27 April 1925, p. 10, 27 May 1925, p. 14, 4 July 1928, p. 16; NSWPD, 11 September 1928, pp. 6–8, 13–14; Australian National Review (Sydney), 20 July 1928, p. 16.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 53-55.