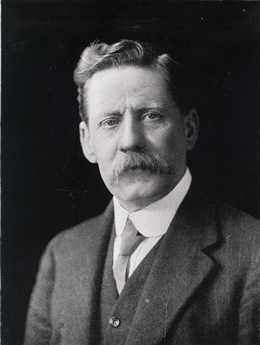

MILLEN, Edward Davis (1860–1923)

Senator for New South Wales, 1901–23 (Free Trade; Anti-Socialist Party; Liberal Party; Nationalist Party)

As Australia’s first Minister for Repatriation, Edward Millen was a central figure in the establishment of Australia’s repatriation policies and machinery. Born in Deal, Kent, on 7 November 1860, the son of John Bullock Millen, a pilot of the Cinque Ports, and Charlotte, née Davis, he began his working life as an adjuster of marine insurance. Migrating to New South Wales around 1880, Millen first worked as a journalist in Bourke and Walgett. He took up grazing leases near Brewarrina, before commencing work on the Central Australian and Bourke Telegraph and the Western Herald and Darling River Advocate. He also ran a land agent business.On 19 February 1883, he married Constance Evelyn Flanagan at Bourke. Having developed an interest in politics, in 1891 he stood unsuccessfully as a Free Trader for the Legislative Assembly seat of Bourke. In July 1894, he recontested the seat and won.[1]In the Assembly, Millen made a name for himself as a land reformer. In debate on the Crown Lands Bill, he implored his fellow members ‘to deal with this measure apart from class interests, and free from party prejudices’.

In 1893, Millen was a foundation member of the general council of the New South Wales Australasian Federation League. In November 1896, he was active at the People’s Federal Convention in Bathurst. In 1897, he stood as a candidate for New South Wales for the Australasian Federal Convention, but was unsuccessful. During debate on the Federation Bill in the Legislative Assembly in 1897, he expressed some serious concerns about the way in which Federation was moving. He stated that equal representation of the states in the proposed Senate would be ‘objectionable and dangerous’. He averred that the New South Wales delegates to the 1897 Federal Convention in Adelaide had been elected because of their capacity for ‘political business’ and their ‘consistent advocacy’ of Federation. He considered that this did not mean that New South Wales had to endorse decisions that the delegates to the Convention had supported. In April 1898, he became a founding member of the Anti-Convention Bill League. He continued to oppose Federation, campaigning energetically for the ‘no’ vote prior to the referendum on Federation in June 1898. He made it clear that the supporters of the ‘no’ vote were ‘not against Federation’, but simply against the terms of the Bill itself.

Despite being welcomed to Bourke by (according to the Western Herald and Darling River Advocate) ‘a Great and Enthusiastic Concourse of People’, Millen, who stood as a Liberal Federal candidate, was defeated at the New South Wales election of July 1898, albeit by a handful of votes. On 8 April 1899, he became, with Albert Gould, one of twelve new members of the Legislative Council whose appointment was Premier George Reid’s final master stroke in bringing New South Wales into the Federation camp prior to the 1899 referendum. Two years later, he stood for the Senate. Elected in March 1901, he resigned from the Legislative Council the following May, retaining his Senate seat until his death.[2]

Millen was one of the first leaders of the Senate, serving in 1901 as deputy to Josiah Symon’s unofficial leadership, and as Leader of the Government in the Senate or Leader of the Opposition in the Senate continuously from 1907 to 1923. ‘As leader of the Senate,’ said W. M. Hughes at the time of Millen’s death, ‘he had no equal’. Labor’s Albert Gardiner spoke admiringly of Millen’s leadership and the respect in which he was held, commenting on his aptitude in managing the business of the Senate. George Pearce would write that Millen had been ‘one of the ablest and most destructive critics the Federal Parliament has ever had’, and one who caused ‘misgiving in the hearts of his opponents’.

Hansard points to Millen’s long and vigorous involvement in debate and the breadth of his interests. A Free Trader, he argued that efficient industry should not require bounties or high tariffs: ‘I say at once if these industries cannot stand after 30 years, like good honest tubs on their own bottoms, they are not entitled to much consideration at our hands’. He supported White Australia, including the immediate cessation of Kanaka immigration and the gradual deportation of those already in Queensland. ‘It is’, he said, ‘not merely a question as to whether or not these coloured races may intermix with our own. There is an equally serious matter, and it is that the introduction of inferior labour would, in my opinion, tend to degrade labour throughout the Commonwealth’. However, it was the events of World War I that led to his greatest challenges and success.[3]

At the outbreak of war, as Minister for Defence in Joseph Cook’s Liberal Government, he declared that Australia was no ‘fair-weather partner’. On behalf of the Government, in April 1914, he had rebuffed Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty, for suggesting that Australia should not retain its own fleet in Australian waters. He tabled a memorandum in the Senate expressing ‘the sharpest criticism of the British’. Privately, he wrote to the Governor-General, Lord Denman, in June, describing Churchill’s suggestion as ‘disastrous’, and emphasising that ‘even if the retention of these vessels in the Pacific reduced their fighting value to nil, I would still urge at the present time that they should remain here’. He added: ‘Australians will not consent to being taxed for the purpose of building docks and other shore establishments for vessels employed on the other side of the world . . . ’. Despite this, the Cook Government placed the navy under British Admiralty control in August 1914. Millen was responsible for the initial recruiting of the AIF and the formulation of defence proposals, but his period as Minister for Defence was short-lived. After the Labor Party won the 1914 election, he became a member of the federal parliamentary war committee, a subcommittee of which investigated repatriation.[4]

In September 1917, Millen became Australia’s first Minister for Repatriation. This was the most significant appointment of Millen’s career. His work would have a far-reaching impact on Australian society. According to Clem Lloyd and Jacqui Rees in their history of Australian repatriation, Millen’s contribution was ‘the most significant’ amongst that of a number of distinguished Australians involved in the establishment of this largely new area of public policy. Millen ‘influenced profoundly the evolution of repatriation at three decisive points: the creation of an Australian war pension scheme following the outbreak of war in August 1914; the definition of concepts underlying the comprehensive repatriation scheme that was embodied in the Australian Soldiers Repatriation Act of July 1917; and the formation in April 1918 of Australia’s first repatriation administration’.

From the outset, Millen understood the ‘magnitude and complexity’ of the proposals he had introduced into the Senate on 18 July 1917. He described repatriation as ‘an organized effort on the part of the community to look after those who have suffered either from wounds or illness as the result of the war’, and ‘to reinstate in civil life all those who are capable of such reinstatement’. He pointed to the national loss ‘if 250,000 men remain unnecessarily idle for one week’.

Millen was an industrious and competent minister, but the establishment of the repatriation department alone was a mammoth task. The new department was staffed with experienced policy administrators and largely inexperienced service personnel. Nowhere was this more apparent than in the controversy in Parliament and the press over the War Service Homes Commission.On 12 December 1918, Millen introduced legislation, which became the War Service Homes Act 1918–19. The Act allowed for the administration of the Commission to be in the hands of a sole commissioner who had an unusually large measure of autonomy. By September 1920, parliamentary concern over the administration of the scheme by the Commissioner, J. T. Walker, and indeed over Walker’s initial appointment by Millen, led to a series of inquiries by the joint committee of public accounts.The affair was complex and raised important issues concerning the Commissioner’s accountability to the Minister and thereby to the Parliament. Professor Wettenhall has written that the parliamentary debates of December 1921 ‘furnish one of the fullest examinations of the difficult question of ministerial responsibility for the actions of an autonomous public corporation in the history of the Commonwealth Parliament’.[5]

Millen’s work as minister appears to have been further complicated by the Returned Sailors and Soldiers Imperial League of Australia lobbying the Prime Minister, W.M. Hughes, on such subjects as increases in war service pensions. In March 1920, Millen had introduced new repatriation legislation, the Australian Soldiers Repatriation Bill. The Bill provided for improved pensions and a paid repatriation commission. It was the protracted debate on this Bill that led Senator Thomas to successfully move that the Senate pass a resolution that the two Houses should consider amending their standing orders in order to enable a minister in one House to appear on the floor of the other. This would have allowed Millen to answer criticisms being made in the House of Representatives by Earle Page and others. In the event, no further action was taken by either House.[6]

An apparent debacle in the administration of the War Service Homes Commission, for which Millen necessarily was responsible, should not devalue Millen’s considerable overall success as Minister for Repatriation as well as his achievements in other significant areas of government activity. As Leader of the Government in the Senate and with Prime Minister Hughes abroad, Millen and the Acting Prime Minister, W. A. Watt, in 1919, brought about a successful end to the seamen’s strike of that year. In 1920, Millen was Australia’s delegate to the first meeting of the General Assembly of the League of Nations in Geneva, securing mandated Pacific protectorates for Australia in the face of Japanese opposition.[7]

In December 1922, Millen successfully contested the federal election, remaining in the Parliament to support Hughes, but retiring from the Ministry in February 1923. In March, he was granted leave of absence from the Senate because of deteriorating health, which, it was believed, had been caused, or at least exacerbated, by the burden of his work during the post-war period. He died on 14 September 1923 at Caulfield in Melbourne. His wife and two daughters, Jessie and Ruby, survived him. The obsequies for Millen were impressive: services in the Queen’s Hall, Parliament House, Melbourne, and at St Stephen’s Presbyterian Church, Sydney, and a State funeral before burial in Rookwood Cemetery, Sydney. Hughes referred to Millen’s life as being ‘a pattern to public men’, and to the fact that he had given his life to the ‘great burden of repatriating our soldiers’. In the Senate, Pearce referred to Millen’s work for repatriation as an ‘enduring monument’, while Hughes, unveiling a monument of a different kind, said: ‘No man did more to make this country what it is than Senator Millen’.[8]

[1] Martha Rutledge, ‘Millen, Edward Davis’, ADB, vol. 10; Clem Lloyd and Jacqui Rees, The Last Shilling: A History of Repatriation in Australia, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1994, pp. 5–6, 63–85, 94–97, 197–199, 412, 419; SMH, 15 September 1923, p. 14; Punch (Melbourne), 7 April 1921, p. 2.

[2] NSWPD, 19 September 1894, p. 584; Reports of the inaugural meetings of the Australasian Federation League, 22 June, 3 and 17 July, 1893, microform, NLA; Proceedings, People’s Federal Convention, Bathurst, November, 1896,William Andrews & Co., Sydney, 1897; NSWPD, 20 May 1897, pp. 593–594; The editor is indebted to Clive Beauchamp for the following newspaper references—SMH, 5 March 1897, p. 5,6 April 1898, p. 7, 6 June 1898, p. 6; Western Herald and Darling River Advocate (Bourke), 22 June 1898, p. 2, 29 June 1898, p. 2, 30 July 1898, p. 2; NSWPD, 11 April 1899, pp. 16–17; Bede Nairn, Civilising Capitalism: The Beginnings of the Australian Labor Party, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1989, pp. 222-225.

[3] Argus (Melbourne), 17 September 1923, p. 16; CPD, 26 March 1924, pp. 3-4; George Pearce, Carpenter to Cabinet: Thirty-Seven Years of Parliament, Hutchinson & Co., London, 1951, p. 74; CPD, 21 May 1901, pp. 65, 68.

[4] C. E. W. Bean, Anzac to Amiens: A Shorter History of the Australian Fighting Services in the First World War, AWM, Canberra, 1961, p. 23; CPD, 16 April 1914, p. 54, CPP. E. D. Millen, Naval Defence, 1914; Malcolm Booker, The Great Professional: A Study of W.M. Hughes, McGraw-Hill, Sydney, 1980, p. 136; Denman Papers, MS 769, NLA; Bean, Anzac to Amiens, p. 25; CPP, Report of the federal parliamentary war committee sub-committee on settling returned soldiers on the land, 1916.

[5] Lloyd and Rees, The Last Shilling, pp. 5–6; CPD, 18 July 1917, pp. 183–196; E. D. Millen, ‘Repatriation: Australia’s Great Post-War Problem’ in Australia To-Day, special no. of the Australasian Traveller (Melbourne), 21 November 1917, pp. 55–71; Argus (Melbourne), 29 January 1919, p. 6, 23 October 1919, p. 6, 5 December 1921, p. 6; CPD, 12 December 1918, pp. 9111–9119; CPP, Final report from the joint committee of public accounts on the war service homes commission, July 1922; R. L. Wettenhall, ‘Administrative Debacle 1919–23’, Public Administration, vol. 23, no. 4, 1964, pp. 307–327; CPD, 2 December 1921, pp. 13551–13621, 8 December 1921, pp. 13995–14044.

[6] Lloyd and Rees, The Last Shilling, pp. 191–199; CPD, 24 March 1920, pp. 641–660, 13 May 1920, pp. 2051, 2067–2069, 2 December 1921, pp. 13583–13589; Senate, Journals, 13 May 1920; H of R, V&P, 2 December 1921.

[7] CPD, 16 July 1919, pp. 10697–10698.

[8] Age (Melbourne), 15 September 1923, p. 15, Argus (Melbourne), 17 September 1923, p. 16; CPD, 26 March 1924, pp. 2-3; on 25 September 1927, at Rookwood Cemetery, Hughes unveiled a monument above Millen’s grave. The inscription referred to his having ‘died in the performance of his duty’, Age (Melbourne), 26 September 1927, p. 10.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 18-22.