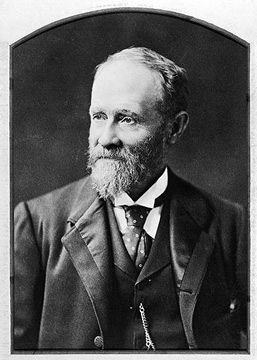

ZEAL, Sir William Austin (1830–1912)

Senator for Victoria, 1901–06 (Protectionist)

William Zeal was born on 5 December 1830 at Westbury, Wiltshire, England, the son of Thomas Zeal, a wine merchant and his wife Ann, née Greenland. Zeal was educated privately at schools in Westbury and Windsor, obtaining a diploma as a surveyor and engineer in 1851. In 1852, he migrated to Australia and headed straight to the Victorian goldfields. He worked for some two years at Forest Creek (Castlemaine) prospecting and running an importing business, but with no success. He returned to Melbourne and worked briefly for an architectural firm before joining the Melbourne, Mount Alexander and Murray River Railway Co. Later describing himself as ‘an old railway man’, he worked as a surveyor, supervising the construction of the line between Footscray and Sunbury. The Victorian Government bought the company in 1856 and Zeal remained in its employ until 1859. He then became general manager for Cornish and Bruce, contractors for the Melbourne–Sandhurst (Bendigo) line from 1859 to 1864.[1]

In 1864, Zeal was elected to represent Castlemaine in the Victorian Legislative Assembly. His campaign was notable for his attack on the competence of the Victorian railways engineer-in-chief, Thomas Higinbotham. The following year, a parliamentary select committee exonerated Zeal of allegations made by Higinbotham that he had acted dishonestly while employed with the railways. Following a pastoral venture with Sir William Mitchell, Zeal suffered financial ruin which led to his resignation from Parliament in January 1866. Back in Melbourne in 1869, he again worked on the railways, designing the Moama–Deniliquin line. He returned to politics and was re-elected for Castlemaine, serving from 1871 until 1874, when he again resigned for business reasons. In 1876, he unsuccessfully contested the Legislative Council seat of South Western Province, but in May 1882 was elected at a by-election to the Council for North Western (later North Central) Province, serving until 1901. Zeal was an ‘Upper House’ man who argued that the ‘thrifty’ classes with ‘a stake in the colony’ were entitled to be protected from the excesses of populism manifested in the ‘Lower Houses’.

His ‘expert knowledge about railways and public works’ resulted in his becoming Postmaster-General in the Shiels Ministry (1892) when he recognised the importance of laying the first Pacific cable. A member of the standing committee on railways, in 1892, he was elected President of the Legislative Council, serving with distinction. In 1895, he was appointed KCMG.[2]

A Victorian delegate to the Australasian Federal Convention (1897–98), Zeal was identified as one of the ‘Liberals as against the Conservatives’ by Alfred Deakin, who, not much impressed by his performance, put his election down to the personal support given by the proprietor of the Age. In the behind the scenes lobbying at the Convention’s Adelaide and Melbourne sessions, Zeal assisted Henry Bournes Higgins and Deakin in gathering support for the confirmation of the 1891 compromise, which had resolved the nature of the Senate’s financial powers. He spoke strongly in support of Higgins’ proposal to vest power in the Federal Parliament to legislate in industrial disputes.

According to the Age, Zeal, who identified himself as a Protectionist, was never at home in the Federal Parliament to which he was elected in 1901. Nominated for the presidency of the Senate by Senators Fraser and Best, Zeal garnered only three votes. However, the procedural knowledge acquired in the Victorian Parliament was put to good use in his membership of the standing orders committee and in his contribution to debate on the forms and procedures of the Senate.[3]

Zeal’s politics exemplified fiscal conservatism tempered by a social liberalism in line with the Deakinite flavour of the time. He attacked ‘extravagant’ estimates for defence expenditure, calling for better value for the defence pound. In comments redolent of the debates of the 1990s, Zeal expressed concern about the level of government debt: ‘The Australians have a larger debt per head than have any other civilized people’. And on another occasion: ‘Are honorable senators aware that amongst the debt-owing countries of the world Australia stands sixth?’ Zeal, concerned that ‘a poor man could not hope to get justice’, attacked proposals for the establishment of the High Court as being ‘unnecessary and most expensive’. He advocated a federal High Court composed of State Supreme Court judges. He attacked too what he saw as improper attempts by the federal government to acquire land from private landholders under compulsory acquisition legislation. He warned that construction costs for the Kalgoorlie to Port Augusta railway were ‘terribly under-estimated’. Zeal was cautious about a federal capital: ‘I know hundreds of Victorians who say they would not object if to-morrow the federal capital were transferred to Sydney. We in Victoria are getting nothing out of this Federal Government’. In relation to the proposal to establish a board of experts to report on the choice of a site, he asked the minister concerned what he imagined ‘this board of experts will cost?’[4] In the tariff debate, Zeal displayed a command of world trade figures, especially on such items as steel and pig-iron. He recognised that protection and free trade attitudes were so strongly held that it was ‘useless for us to waste much more time in discussing this matter’, and that ‘we should use our own common sense, and bring this eternal controversy to a conclusion’.

A broad-minded liberalism was apparent in other issues. He supported the right of ministers to make senior bureaucratic appointments, and to manage their departments without undue interference—especially from the states. Although believing that a woman was best employed ‘looking after her . . . husband and family’, he nevertheless argued against placing ‘any disability on the employment of women’. He attacked the Victorian Government for its continued refusal to enfranchise women and was anxious that federal electoral legislation should provide for postal voting so as ‘to protect the women in the bush’. His sense of social justice, combined with an awareness of political advantage, was manifest: ‘In granting the suffrage . . . we are doing something new so far as great communities are concerned . . . There are many people who hold strong opinions against the extension of the franchise to women, but I urge them to remember that women have as much sense in the practical affairs of life as men . . .’. (In 1889 he had been a keen supporter of divorce law reform in Victoria.) Zeal also displayed concern for the Kanaka workers in Queensland: ‘I only want fair play for the kanaka as well as the white man . . . a popular decision is not always correct . . . it is the duty of honorable senators not always to swim with the stream. There is nothing easier in the world than to agree with the mass of the people. It is certainly safest to do so in politics’.[5]

He was unconcerned about editorial opinion: ‘So long as I do what I think is right I am independent of all the newspapers in existence . . . ’. Nor was he afraid to change his position: ‘Is there a politician of any eminence in Australia who has not changed his mind on particular subjects?’ His parliamentary speeches show glimpses of wit, devoid of any sense of invective or abuse. He was also a great believer in short speeches: ‘If senators cannot say all that they desire to say within that period [thirty minutes] they ought not to speak at all. I am quite sure that if everyone adopted the practice of making only short speeches, an all-round advantage would be conferred, and the reputation of this Chamber would be considerably enhanced’.[6]

He decided not to stand for re-election in 1906 and returned to his Melbourne business activities. He held directorships, and was chairman of Goldsbrough Mort and Co. (1897–1912), the Victorian branch of the Australian Mutual Provident Society (1899–1912), the Perpetual Executors and Trustees Association (1895–1912) and the London Guarantee and Accident Co. Closely involved with banking, he was an auditor, and director (1883–1912) of the National Bank of Australasia and had helped devise a scheme of management to prevent the Bank from going under in the crash of 1893. He was a member of the Institution of Civil Engineers, London, and a Prahran City councillor (1879–82).

Zeal never married. One contemporary profile of him commented: ‘To the casual observer he looks crusty, crabbed, perhaps vinegary. He is unmistakably a bachelor, and a lonely bachelor at that’. Despite this assessment, Zeal was known as a man of considerable style, charm and generosity, with manifest social graces and a fondness for giving dinner parties which were recognised as ‘the most charming of feasts’.

Sir William Zeal died at his Toorak home on 11 March 1912 and was buried in the Melbourne General Cemetery. His estate was a large one and provided for the establishment of a charitable trust and for the donation of his extensive art collection to the Bendigo Art Gallery. Had a parliamentary epitaph been required words addressed to him by Sir John Madden would have fitted the bill: ‘You have never failed to remember what great things the honour and independence and dignity of Parliament are’.[7]

[1] Geoff Browne, ‘Zeal, Sir William Austin’, ADB, vol. 12; James Smith (ed.); The Cyclopedia of Victoria, vol.1, 1903, Cyclopedia Company, Melbourne, pp. 152–153; CPD, 14 December 1904, p. 8441.

[2] VPP. Report of the select committee on Victorian railways—Keilor contract, 1864–65; Punch (Melbourne), 14 December 1905, p. 848.

[3] Alfred Deakin, ‘And Be One People’: Alfred Deakin’s Federal Story,with an Introduction by Stuart Macintyre, MUP, Carlton South, Vic., 1995, pp. 67, 84; AFCD, 27 January 1898, p. 183; Age (Melbourne), 12 March 1912, p. 6; CPD, 9 May 1901, pp. 14-15; Symon Papers, MS 1736, NLA.

[4] CPD, 8 October 1902, pp. 16561-16562, 4 June 1903, pp. 514–521, 7 November 1901, p. 6975, 14 March 1902, p. 10960, 21 June 1901, p. 1446, 4 July 1901, p. 2024, 14 December 1904, p. 8441, 7 October 1902, p. 16488.

[5] CPD, 14 May 1902, pp. 12548-12552, 7 November 1901, p. 6971, 2 October 1901, p. 5429, 8 November 1901, p. 7049, 9 April 1902, pp. 11490–11491, 28 November 1901, pp. 7976-7977.

[6] CPD, 2 October 1901, p. 5430, 28 November 1901, p. 7976, 8 October 1902, p. 16562.

[7] Michael Cannon, The Land Boomers, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1995, pp. 238–239; Geoffrey Blainey, Gold and Paper: A History of the National Bank of Australasia Limited, Georgian House, Melbourne, 1958; Punch (Melbourne), 14 December 1905, p. 848; Age (Melbourne), 12 March 1912, p. 6; Table Talk (Melbourne), 6 May 1892, pp. 4-5; Letter, Lieutenant-Governor of Victoria, Sir John Madden, to Zeal,4 September 1900, Symon Papers, MS 1736, NLA.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 285-288.