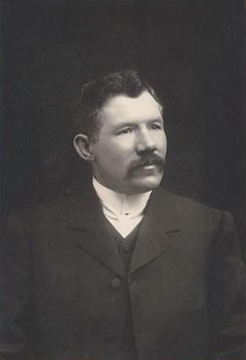

HENDERSON, Christopher George (1857–1933)

Senator for Western Australia, 1904–23 (Australian Labor Party; National Labour Party; Nationalist Party)

Christopher George Henderson was born at Bedlington, Northumberland, England, on 19 August 1857, to George Henderson of Rothesay, Scotland, and Jane, née Short. At the time of her son’s birth, Jane could neither read nor write. Christoper George began his working life at the age of eight or nine years as a pony boy in a Northumberland coal mine. At fifteen, he became a coalminer in the Newcastle district, and in his spare time improved his education by attending classes at the Miners’ Hall. In 1880, he married Ann Vietch at the Holy Cross Church, Ryton, County Durham.[1]

The family arrived in Australia on 5 October 1885, and Henderson (who was known as George) found employment as a coal miner at Bulli, New South Wales. He was general secretary of the Illawarra District branch of the Miners’ Union from 1891 until 1899 when he and his family moved to the Western Australian mining town of Collie. There, he became the manager of Wallsend Coal Mine and then general secretary of the Miners’ Union of Western Australia, a position which he held until 1904, when he entered the Senate. In 1901, he had unsuccessfully contested the seat of South-West Mining for the Western Australian Legislative Assembly.

Henderson was noted for his jovial personality and his untiring efforts to improve the conditions of his fellow workers. He established the principle of cooperative trading in both the Illawarra and Collie districts and helped to found the Collie Co-operative Society and the Collie Progress Committee. He also served as a member of the Collie Municipal Council for four years.[2]

Henderson was elected to the Federal Parliament as a Labor Senator for Western Australia in December 1903. In his first speech on 4 March 1904, he advocated that debts, which had been incurred by the pre-Federation governments, should come under federal control. He pressed for the adoption of uniform rates for old-age pensions throughout Australia, for direct taxation, and for the completion of a transcontinental railway to link Western Australia with the eastern states. Like many Labor parliamentarians, he argued strongly for the retention of the Immigration Restriction Act, and against the importation and industrial exploitation of aliens, while Australian workers were unemployed. Henderson’s concern, however, extended beyond Australia for he supported a motion of protest against the introduction of Chinese labour into the Transvaal until a referendum ‘of the white population of that Colony’ had been taken or responsible government granted.[3]

Another early matter on which Henderson expressed an opinion revealed his foresight regarding the needs of the Australian federal capital. He supported the second reading of the Seat of Government Bill, stating that there was a need to review the size and location of the proposed Federal Capital Territory in the light of Parliament’s obligation to future generations. He believed that the Territory needed to be extended beyond the original 100 square miles set aside for it (the present Australian Capital Territory is approximately nine times that size) and that there should be a ‘free port open to the wide ocean’. He did not object to the Territory being located within New South Wales, but he opposed attempts by that state to maintain control over it.[4]

Much of Henderson’s time in the Senate was spent discussing industrial reforms, which would protect unionised workers. He was a powerful advocate of the system of conciliation and arbitration as a means of settling industrial disputes. He also supported a proposal to stamp goods with a trade union mark to enable buyers to be confident of purchasing union-made goods. This was opposed by some conservatives, such as Senator Best.[5]

Ironically, in view of his departure from the Labor Party in 1917, Henderson was a strong party man. Early in his first term as senator, he declared: ‘First of all, we are a Labour Party, and whatever else we may be, is a secondary consideration … the Labour Party have never yet asked a legislative assembly in Australia to place on the statute-book any law that is not humane in its every instinct—that has not for its ultimate object the uplifting and the general welfare of the people’.

From 1910 to 1914, Henderson served as Temporary Chairman of Committees. In 1913, he was a member of the select committee on the case of Henry Chinn. This committee was set up to inquire into the dismissal from government service of Chinn, a civil engineer and licensed surveyor, on the grounds of inefficiency. The inquiry sparked a lengthy debate in the Senate on 5 November 1913, when Liberal Senators Oakes and Gould challenged the inquiry’s credibility by suggesting that its powers were too limited to carry out an effective examination of the case.[6]

During World War I, George Henderson was one of five Western Australian Labor senators who came to support the conscription of men for overseas military service. He had not always held this position. Shortly before the commencement of the Gallipoli campaign in April 1915, he had spoken strongly against ‘so barbarous a principle’ as the adoption of conscription for military service overseas, saying that he placed his faith in the ‘manhood and patriotism’ of young Australians. It appears that this faith later deserted him, and his strong pro-conscriptionist stance led to the severing of his ties with Labor—a party which he had believed always stood for justice.[7]

At a referendum on 28 October 1916, by a narrow majority, the Australian people voted against Prime Minister Hughes’ proposal to introduce conscription. Hughes, continuing to support conscription, split the Labor Party by walking out of a Caucus meeting with twenty-three of his supporters on 14 November 1916. The Governor-General then commissioned Hughes to form a new National Labour Party Government. Hughes was assured that the Liberals would cooperate to enable him to govern. In February 1917, after negotiations with federal Liberal politicians, Hughes agreed to head a Nationalist Government consisting of those in favour of conscription from the Labor and Liberal parties.[8]

Anti-conscription Labor Party members demanded the expulsion of their state and federal colleagues who supported conscription. In December 1916, delegates at an interstate Labor conference in Melbourne voted 29 to 4 in favour of expelling all federal members of Parliament who had joined the National Labour Party. Western Australia was the only state to vote against the resolution. The conference’s ruling meant that Henderson and his Senate colleagues—Hugh de Largie, Richard Buzacott, George Pearce and Patrick Lynch, as well as Reginald Burchell, MP, automatically severed their connection with the Labor Party when they joined the new coalition.[9]

Henderson and his federal pro-conscription colleagues defended their action in joining Hughes on the grounds of ‘the fundamental principle of freedom of conscience to Members of Parliament upon big National questions which are not provided for in the Labour Platform’. They argued that by returning to the ‘Official Labour Party’ (as had been suggested by the state executive of the Australian Labour Federation of Western Australia) they would be ‘bound by the decisions of the State Executives of the other States’. They claimed that if they accepted this position, ‘neither we nor the electors would ever know where we were, as we should be bound to a policy which may be altered at any moment at the whim of these Executives’. The federal members also claimed that conscription was a logical extension of the Labor platform which supported the Defence Act of 1903, and that it was merely a tool to assist in winning the war. They reminded the state executive of Andrew Fisher’s pledge in 1914 that if Labor was returned to power it would do its utmost to prosecute the war to a successful conclusion.[10]

Those against conscription now moved quickly. At a special congress, held in Perth in March 1917, an overwhelming majority of 134 to 30 delegates resolved that, although the state executive of the Australian Labour Federation of Western Australian could not expel any member for supporting conscription, Henderson and his fellow pro-conscriptionists had broken their connection with the Labor Party by joining the Nationalist Party.

Clearly, while the dissenting members were not expelled on the grounds of their pro-conscription beliefs, these beliefs allied them with Liberal politicians, and this was the stated reason for their removal. The differences of opinion over the conscription issue that drove some members into the Opposition were held by some Labor anti-conscriptionists to be insoluble.

In his remaining years in the Senate, Henderson took up the cause of returned servicemen and their dependents. He was adamant that the Canteens Funds Bill should include a clause providing for the payment of a lump sum to soldiers or their dependents, so that funds could be dispensed as quickly and efficiently as possible to the needy. He identified four ‘classes’ of beneficiaries: blinded servicemen, soldiers’ widows, the mothers of deceased soldiers, and children or other dependents of deceased soldiers. Henderson spoke eloquently in support of the Bill: ‘There are children to be provided for, and unless we wish to keep them dog poor, unless we are prepared to give them only a red herring and a slice of bread, we must discard all the amendments which have been suggested, and accept the Bill as it stands’.[11]

Henderson also argued against a suggested amendment to the Australian Soldiers’ Repatriation Bill, which would involve the federal government providing funding for cooperative ventures. He stated that the NationalistParty Government was doing ‘almost everything that is humanly possible for our returned soldiers’ and it should not now be asked to find money for ‘co-operative concerns’.

Henderson had long supported home rule for Ireland. In August 1921, he continued to advocate dominion status, rather than independence for Ireland, claiming that an independent Ireland outside the British Empire would be ‘a menace’ both to the Empire and to itself.[12]

Like many of his colleagues who crossed the floor permanently over the conscription issue, Henderson did not remain long on the conservative benches. After his defeat in the 1922 general election, he embarked on a career in real estate, and farming. Henderson died in Sydney on 21 January 1933 and, after a Presbyterian service, was buried in the Northern Suburbs Cemetery. His wife and daughter, Stella, survived him. His death passed unnoticed in the Senate where he had served for three terms.

[1] Information supplied by Mr I. Mears (descendant), and correspondence from Mrs M. Mears to Suzanne Rickard, 23 May 1996.

[2] J. S. Battye (ed.), The Cyclopedia of Western Australia, vol. 1, 1912, Hussey & Gillingham, Adelaide, p. 306.

[3] CPD, 4 March 1904, pp. 135–139, 16 March 1904, pp. 553, 570–571.

[4] CPD,1 June 1904, pp. 1772–1773.

[5] CPD, 4 March 1904, p. 137, 11 August 1904, pp. 4114–4115.

[6] CPD, 8 September 1904, p. 4399, 5 November 1913, pp. 2862–2889.

[7] CPD, 23 April 1915, p. 2593.

[8] C. M. H. Clark, A History of Australia: ‘The Old Dead Tree and the Young Tree Green’ 1916–1935, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1987, pp. 40–45.

[9] State executive of the Australian Labor Federation, Western Australia, correspondence file no. 68, accession no. 1688A, Battye Library, LISWA; ALP, Report of proceedings of the special Commonwealth conference on conscription, Melbourne, December 1916; Westralian Worker (Kalgoorlie), 12 January 1917, pp. 5, 6.

[10] These arguments are set out in two statements to the state executive and signed by the six federal members of Parliament who supported conscription—see state executive of the Australian Labor Federation, Western Australia, correspondence file no. 45, Battye Library, LISWA.

[11] Minutes of a special congress of the Australian Labor Federation, accession no. 1573A/18, 20 March 1917, p. 205, Battye Library, LISWA; CPD,21 April 1920, p. 1357.

[12] CPD, 29 April 1920, p. 1591, 24 August 1921, p. 11220.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 356-360.