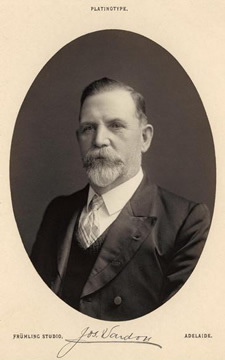

VARDON, Joseph (1843–1913)

Senator for South Australia, 1907, 1908–13 (Anti-Socialist Party; Liberal Party)

Joseph Vardon, printer, was born on 27 July 1843, in the small South Australian town of Hindmarsh, the eldest son of Ambrose Edward Vardon, a shoemaker, and Elizabeth, née Painter. Joseph’s parents were among the earliest colonists of South Australia having arrived in the colony in 1839. Joseph received his elementary education at Moody’s School in Hindmarsh and James Bath’s school in North Adelaide. He left school at the age of ten and for some years was an itinerant farm worker, humping his swag from Hindmarsh to Mount Lofty while looking for work.

In his mid-teens, Vardon was apprenticed to an Adelaide printer, subsequently establishing himself as a tradesman in the city. On 26 December 1864, he married Mary Ann Pickering. They were to have eight children, five sons and three daughters. By 1870, Vardon was involved in publishing the Strathalbyn Southern Argus and in 1874 established his own printing and publishing company, Webb, Vardon and Pritchard. The firm became Vardon and Sons and grew to be one of Adelaide’s largest printing firms. (As Vardon Price, it was taken over by the Advertiser in 1960.) Vardon also served as president and secretary of the South Australian Typographical Society and belonged to the Master Printers’ Association.

A director of the Adelaide Fruit and Produce Exchange Company, Vardon was an earnest and conscientious businessman who, believing in community service, undertook philanthropic work in Hindmarsh. A deacon of the South Australian Congregational Union and at one time its lay chairman, Vardon was a Freemason, a member of the Lodge of Oddfellows and closely associated with the Young Men’s Christian Association, serving as president (1904–08). He was also a member of the Australian Natives’ Association.[1]

He began his political career with sixteen years in municipal government, including six years as councillor and alderman in the City Corporation and four years as an alderman of Unley. From 1888–91, he served as mayor of Hindmarsh. His early interest in politics and public affairs is evidenced also by his membership of the South Australian Literary Societies’ Union Model Parliament from 1884.

At the 1890 election, Vardon stood twice for the House of Assembly, first for Yorke Peninsula; then, when defeated, trying for West Torrens, where he was again unsuccessful, as he was for the same seat at the 1896 election. Finally in 1900, he was returned to the Legislative Council for the Central District. A member of the Effective Voting League, in 1902 Vardon moved the second reading of the Effective Voting Bill, when he referred to Catherine Helen Spence’s advocacy of proportional representation. Apart from his opposition to the reform of the Legislative Council, Vardon was considered a ‘moderate Liberal’. He became Commissioner of Public Works and Minister of Industry (July 1904–March 1905) in the Jenkins Ministry and Chief Secretary and Minister of Industry (March 1905–July 1906) in the Butler Ministry. Despite the death of his wife of forty-one years in 1905,Vardon continued to participate actively in political life.[2]

At the December 1906 federal election, Vardon, who had supported Federation, resigned from the South Australian Parliament to stand for the Senate as an Anti-Socialist. The contest between Vardon and two other candidates, Reginald Blundell and Dugald Crosby, for the third Senate seat was close, and on 8 January 1907, Vardon was declared the victor. Shortly afterwards, Dugald Crosby died, and Blundell lodged a petition for a recount with the High Court of Australia (acting as the Court of Disputed Returns). Vardon was sworn in as a Senator on 20 February 1907, but in June Mr Justice Barton declared Vardon’s election void because of the classification of certain ballot papers as informal. The Governor of South Australia then declared that a casual vacancy had occurred, and at a joint session of the South Australian Parliament, James Vincent O’Loghlin, was chosen to fill the vacancy.

Vardon, contending that this was not a casual vacancy but a failure of the electoral process, approached the High Court requesting a re-election. However, the Court ruled that the matter was beyond its jurisdiction; that it was for the Senate itself to say whether a ‘vacancy’ had occurred in South Australia, or to legislate in order to give the Court the necessary authority. Accordingly, on 23 August 1907, Vardon petitioned the Senate, O’Loghlin having already taken his seat. The Senate referred the petition to its committee of disputed returns and qualifications. The committee, chaired by Vardon’s fellow South Australian, Josiah Symon, presented its report on 9 October 1907, concluding that ‘there was not a vacancy within the meaning of Section 15’ and declared that O’Loghlin was not duly chosen or elected as a Senator.

The Government then ensured the speedy passage through the Parliament of the Disputed Elections and Qualifications Bill which enabled the Parliament to apply to the High Court for a ruling on what was considered to be a ‘difficult point of Constitutional Law’. The Court ruled O’Loghlin’s appointment to the Senate absolutely void. In February 1908, a supplementary election for the Senate in South Australia was held. Vardon won with ease and on 17 March 1908 swore the Oath of Allegiance for the second time.[3]

Vardon was inclined towards brevity in debate and was somewhat bemused by the fact that ‘there were men in the Senate who were capable of speaking continuously for six or seven hours’. Nevertheless, he made his views clear on a number of issues. On 18 March 1908, he announced that he was not an advocate of ‘what is called the new protection’. He reminded the Senate that the electors of South Australia expected him to look to their interests: ‘I shall not support high, and even prohibitive, duties, but shall endeavour to give a reasonable amount of protection to those who need it, whilst offering every encouragement to our primary producers’. (He would later support the Government’s establishment of a Commonwealth agricultural bureau.) Referring to the needs of the printing trade, he mentioned that the printers feared competition with Japan.[4]

Vardon was adamant that his State needed a railway that would connect it with the Northern Territory, seeing this also as important in terms of defence. On the latter, he supported the cadet system of voluntary military training, but confessed that he did not ‘like the idea of compulsion’. He considered that Australia required a small, well-trained, standing army of 40 000 or 50 000 men. As in the South Australian Parliament, he supported proportional representation. ‘I believe’, he said, ‘that all parties in the community ought to be represented’. By 1911, with the Labor Party in a majority in both Houses, he declared that, unless party rule in the Senate could be prevented by the adoption of proportional representation, there might be a justification for the abolition of the Senate. He did not oppose Yass–Canberra as the federal capital site, though, following a visit to the Cotter River, he queried the adequacy of the water supply for the proposed capital.[5]

As an employer in the printing and publishing industry, Vardon regarded his early years in the ‘ranks of labour’ as having provided him with valuable insights into the workplace. He did not, however, support the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration. He reasoned that industrial matters should be left in the hands of the states, as the conditions that prevailed in any one state were different from those obtaining in another. He preferred the principle of state wages boards, which, in his opinion and experience, cultivated ‘the idea of conference, of conciliation, of mutual goodwill, and of a community of interests as between capital and labour . . .’.[6]

Vardon, who was an active member of the Congregational Church, and not shy of referring to the Deity in the Senate chamber, had a high regard for family life and the simple homespun virtues. He considered a tax on pianos was a tax on the home, the piano being ‘the means of keeping the family together, and out of mischief’. Similarly, he thought that there should be no tariff on patterns for home dressmakers as this would disadvantage ‘the daughters of our homes’, though, from comments about the Senate’s Usher of the Black Rod, it is clear that he had no truck with ‘frills and fripperies’. He did, however, in 1911, become a member of the parliamentary delegation that visited England on the occasion of the coronation of King George V.[7]

In the volatile political atmosphere surrounding the May 1913 federal election, Vardon appeared disturbed by one particularly rowdy campaign meeting in the Exhibition Building in Adelaide, at which the Prime Minister, Joseph Cook, was the principal speaker. As chairman of the meeting, Vardon’s remonstrances for peace fell on deaf ears as a white cockatoo was let loose in the hall. Subsequently, Vardon was defeated. Two months later, on 20 July 1913, he died at Unley Park. On 19 July, a journalist from the Register, who had interviewed him the day before his death concerning the resignation of the Liberal Union’s general secretary, recorded Vardon’s last public statement: ‘I have always gone on this principle. Find out what was right and stick to that. I’ve tried to do that, anyhow’. But with the consolidation of the two-party system, he may have found such an ideal increasingly difficult to uphold.

Vardon was buried at Hindmarsh Cemetery. One daughter and four sons survived him. In 1916, the King’s Park Congregational Church was renamed the Vardon Memorial Church in honour of his work for the Church. One son, Edward Charles, carried on his father’s tradition of service to the South Australian and Commonwealth parliaments. Obituaries in the Adelaide papers point to the great esteem in which Joseph Vardon was held as a citizen and parliamentarian, and as founding president of the Liberal Union.[8]

[1] Advertiser (Adelaide), 21 July 1913, pp. 15, 18; Malcolm Saunders, ‘Vardon, Joseph’, ADB, vol. 12; Quiz (Adelaide), 3 March 1905, p. 13; H. T. Burgess (ed.), The Cyclopedia of South Australia, vol. 1, 1907, Cyclopedia Company, Adelaide, p. 179; Mail (Adelaide), 18 May 1912, p. 8; Personal communication between Mrs Molly Vardon and the author, 28 November 1994; Advertiser (Adelaide), 7 December 1960, p. 12, 14 January 1961, p. 8.

[2] Burgess, The Cyclopedia of South Australia, p. 488; Derek Drinkwater, ‘Federation Through the Eyes of a South Australian Model Parliament’, Papers on Parliament, November 1997, Department of the Senate, Canberra, pp. 121–133; South Australian Literary Societies’ Union Parliament, Hansard, 8 May 1884, NLA; CPD, 18 March 1908, p. 9169; SAPD, 1 October 1902, pp. 247–248, 2 September 1903, pp. 90–93, 4 October 1905, pp. 103–105; Advertiser (Adelaide), 27 December 1906, p. 4.

[3] P. Loveday, A. W. Martin & R. S. Parker (eds), The Emergence of the Australian Party System, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1977, p. 430; Advertiser (Adelaide), 22 December 1906, p. 9; Geoffrey Sawer, Australian Federal Politics and Law, 1901–1929, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1956, pp. 80–82; Blundell v. Vardon (1907) 4 CLR 1463; The King v. The Governor of the State of South Australia (1907) 4 CLR 1497; CPP, Report of the committee of disputed returns and qualifications on the petition of Joseph Vardon, 1907; G. S. Reid and Martyn Forrest, Australia’s Commonwealth Parliament 1901–1988, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1989, pp. 109–110;Vardon v. O’Loghlin (1907) 5 CLR 201; J. R. Odgers, Australian Senate Practice, 6th ed., Royal Australian Institute of Public Administration, Canberra, 1991, pp. 172–173; CPD, 17 March 1908, p. 9040; the Senate’s committee of disputed returns and qualifications has not met since 1907.

[4] CPD, 22 July 1909, p.1517, 18March 1908, pp. 9163–9164, 17 September 1908, p. 92, 27 October 1909, pp. 5045–5047, 26 March 1908, p. 9681.

[5] CPD, 3 December 1909, p. 6833, 17 September 1908, pp. 91–93, 25 October 1911, pp. 1776–1781, 20 October 1909, p. 4707.

[6] CPD, 8 October 1908, p. 930, 17 September 1908, p. 94, 18 August 1910, p. 1699, 22 July 1909, p. 1497.

[7] G. B. Payne and E. Cosh, History of Unley 1871–1971, City of Unley, SA, [1972], p. 165; CPD, 6 September 1911, p. 97, 31 March 1908, p. 9840, 9810, 10 December 1908, p. 2994.

[8] Advertiser (Adelaide), 23 May 1913, pp. 9, 11; Register (Adelaide), 21 July 1913, p. 8; CPD, 13 August 1913, p. 86; Don Temby, To Seek Fresh Fields, Saint Andrew’s Manthorpe Uniting Church, Unley Parish, 1992, pp. 41, 85.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 179-182.