WALKER, James Thomas (1841–1923)

Senator for New South Wales, 1901–13 (Free Trade; Anti-Socialist Party)

James Thomas Walker, banker, federalist and ‘out-and-out free-trader’, was born on 20 March 1841 in Leith Walk, Midlothian, Scotland, to John William Walker, grazier, and Elizabeth, née Waterston. In 1844, John William moved to Australia with his family, settling on Castlesteads Station, Boorowa, in New South Wales. After four years, he sold the property to Hamilton Hume, the explorer, and the family returned to Scotland where James Thomas attended Circus Place School and the Edinburgh Institution.

At sixteen, Walker joined the paper manufacturing firm, Cowan & Sons, in Valleyfield, near Edinburgh. He resigned after six months to work for Robert Allan, stockbroker and agent for the Phoenix Fire Office in Edinburgh. In 1860, Walker started as a junior clerk with the Bank of New South Wales in London. This ambitious young man, efficient and trustworthy, looked to Australia for advancement and in January 1862 sailed for Melbourne on the Swiftsure. He arrived on 19 April and headed north to rejoin the Bank of New South Wales at its head office in Sydney. The Bank sent him to Rockhampton as an accountant, where he adjusted readily to life in central Queensland and became a valued member of the community.

Walker lived by the philosophy that hard work brings its own rewards. In 1866, he became the first manager of the Bank’s Townsville branch, and from 1867 to 1878 managed the Toowoomba branch, in 1871 acting as inspector in Brisbane. Promoted to assistant inspector in 1878, he resigned in 1885 to become general manager of the Royal Bank of Queensland. Two years later, he moved to Sydney to manage the estate of his cousin, the late Thomas Walker of Yaralla. While in Queensland, on 16 April 1868, Walker married Janette Isabella Palmer from Range View near Toowoomba.[1]

During the 1890s, Walker joined the Australasian Federation League of New South Wales. He became one of its most active members, and in November 1896 attended the People’s Federal Convention in Bathurst, which used the draft Commonwealth Bill of 1891 as a basis for discussion. Walker tackled the troublesome subjects of trade and finance. He outlined the savings that would accrue under a scheme that he had developed on state revenue and federal expenditure. His plan was well received, and Walker, confident that the financial outlook would no longer be a deterrent to Federation, observed: ‘We have heard of various “lions” in the path of Federation; it seems to me that the Financial Lion has been slain. The two still in existence are Indifference and Distrust’.

As a staunch federalist, Walker was committed to removing these obstacles. So far, he had shown little interest in politics—he came from the financial and banking world. Walker was a fellow of the Institute of Bankers, a former vice-president of the Australian Economic Association and a director of the Australian Mutual Provident Society; he had been a director of the Bank of New South Wales since 1889 and was soon to become its president. It was his able exposition of the financial implications of Federation that resulted in his election in 1897 to the Australasian Federal Convention.

During the first session of the Convention in Adelaide, Walker, despite some nervousness, addressed the assembly. He believed that the proposed states should have equal representation in the upper House, urged the consolidation of states’ debts and Commonwealth control of railways, defence and quarantine. He wanted the national capital to be on federal territory and not to be one of the existing capitals. Turning to his own area of expertise, Walker again outlined his financial scheme for the Commonwealth. However, despite his public standing as ‘the doyen of Finance’, the New South Wales delegation overlooked him when choosing their representatives for the finance and trade committee. Disappointed, Walker confided that he was put on the judiciary committee instead of that on finance and trade because of the ‘superior political claims’ of others.

Later dismissed by Alfred Deakin as a ‘mere commercial man’, nonetheless Walker took his place among the ablest politicians in Australia in formulating the federal Constitution. Much to Edmund Barton’s annoyance, he successfully moved to have the name of the second chamber changed from ‘States Assembly’ to ‘Senate’. With less success, he proposed that the Constitution be known as the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australasia, looking to the inclusion of New Zealand, Fiji and New Guinea. He wanted to set the minimum age for Senators at twenty-five rather than twenty-one, and to have Patrick Glynn’s proposal for the ‘Divine Sovereign’ recognised in the Constitution.

At its second session in Sydney in September 1897, the Convention delegates, unable to agree on the financial clauses, appointed a subcommittee to consider and report on federal finance. On this occasion, Walker’s credentials were recognised. He was chosen to serve on the committee, which presented a plan (based on his bookkeeping scheme) that was eventually accepted by the Convention. Walker considered this an equitable arrangement ‘by means of which each of the colonies will get back what it pays, less its proportionate share of the expenses’.[2]

During the referendum campaigns in New South Wales in 1898 and 1899, Walker addressed public meetings in Sydney and in country areas from Albury to Tenterfield. He pointed out the likely advantages of Federation for intercolonial trade, government economy, the growth of nationhood as opposed to provincialism, more effective defence and more efficient quarantine systems and postal and telegraphic services. He gave ‘yeoman service’, compiling and printing at his own expense pamphlets on federal finance. In 1899, he travelled to Western Australia to help rally support there.

Walker’s contribution to the federal cause was not lost on the people of New South Wales, a petition of over 6500 signatures encouraging him to stand for the Senate. With characteristic enthusiasm and dedication, Walker, often accompanied by Albert Gould, stumped the countryside preaching the merits of free trade. Topping the poll, he took his seat in the Senate on 9 May 1901. He hoped that the Senate would not degenerate into a party House, that members would take a broad, independent view of national matters, but would nevertheless be prepared to safeguard the interests of their states. On his initiative, the standing orders committee framed an order providing for the day’s proceedings to open with prayer. Walker trusted the practice would do ‘something to increase the spirit of reverence in this rising community’.

In his first parliamentary term, Walker pushed for the construction of a transcontinental railway, the selection of a site for the federal capital and for equal pay for women doing the same work as men. Although a Free Trader, he approved of ‘vanishing bounties’, but argued against protective duties. While acknowledging the benefits of a federal old-age pension scheme, he believed that the Commonwealth did not have the resources to fund such a scheme.

Walker favoured a White Australia, but was critical of the Immigration Restriction Bill, particularly the provision for a dictation test, which he described as ‘a legal subterfuge’. He supported Senator Macfarlane’s amendment for the test to be in a European language known to the immigrant. When this failed, he moved his own amendment, but it was also defeated. He advocated a gradual reduction in Kanaka labour, and moved that those who had been resident in Australia for at least five years be allowed to remain. In 1902, he urged the Government to exercise discretionary power to ensure that Kanaka deportation be administered in a humane way.[3]

Walker believed in freedom of contract, protested against union preference and denounced compulsory arbitration. He wanted it made a punishable offence to call a man who had the courage to leave a union, a ‘scab’ or a ‘blackleg’. In 1904, he opposed the Conciliation and Arbitration Bill. He considered that it was ‘conceived by the Barton Government, incubated by the Deakin Ministry, god-fathered and god-mothered by the Watson and Reid-McLean Ministries, and now the Senate is asked to give it its blessing, when we ought really to give it its quietus’.

In 1901, he was a dissenting member of the committee of elections and qualifications that inquired into a petition against the return of Alexander Matheson as a senator. He insisted that the right to petition ought not to be dismissed on mere technicalities, and would have liked the opportunity to record the reasons for the minority’s dissent. It was this inquiry which helped to convince him that there should be an independent legal body to deal with electoral matters.[4]

In 1906, Walker, who said that he could not stand the politics of Labor, ran successfully for re-election as an Anti-Socialist. He believed Federation had not fulfilled the expectations of the Australian people, and that the prevailing feeling of unrest and dissatisfaction was due to the three-party system. He stressed that it was ‘incumbent upon the electors to vote for either socialism or anti-socialism, and so end this triangular government’. In an article he wrote for Commonwealth, a newspaper founded and edited by J. G. Drake, Walker again expressed his reservations about Commonwealth–state financial arrangements.

During his second term, Walker continued to support the construction of the transcontinental railway. In 1906, he pointed out that in New South Wales, the question of the federal capital was a ‘burning one’; five years on, he noted that it still seemed to be ‘slowly dragging its weary length along’. He argued that the immigration rate must be accelerated if Australia were ‘to progress otherwise than at the existing snail’s pace’, again asking for greater elasticity and humanity in the application of the Immigration Restriction Act.

The banking crises of 1893 had left a lasting impression on Walker. In 1908, he was responsible for the introduction of the Commonwealth Companies Reserve Liabilities Bill, which allowed joint stock companies, especially banks, to accumulate special reserve funds for the purpose of meeting shareholders’ liabilities in a crisis. It was followed in 1910 by a similar bill, somewhat narrower in scope—the Commonwealth Banking Companies Reserve Liabilities Bill. Frustrated with the difficulties of piloting private senators’ bills through Parliament, he complained in 1912: ‘There seems to be no chance for a man with special knowledge to get a Bill passed’.[5]

Walker did not contest the 1913 federal election. Despite poor heath, he remained interested in politics, and kept in contact with former parliamentary colleagues. He had been president of the Australian Golf Club, chairman of the Thomas Walker Convalescent Hospital, a director of the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital and of Burns, Philp & Co., member of the Highland Society and on the executive committee of the Young People’s Industrial Exhibition (1901), and of the Presbyterian Church. He remained a director of the Australian Mutual Provident Society until 1921 and a councillor of St Andrew’s College at the University of Sydney until 1922.

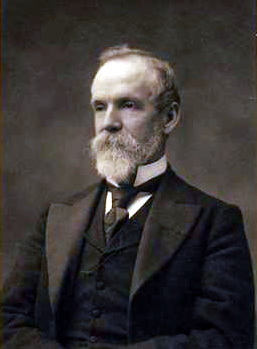

He died on 18 January 1923 and was buried in the Presbyterian Cemetery, South Head, Sydney. His wife, two daughters, Emily and Janette, and three sons, Alexander, Egmont and George, survived him. Two other sons predeceased him. (His wife had avoided public functions since 1902 when their eldest son, Archibald, resident magistrate in New Guinea, died, aged thirty-three.) Walker’s sharp features, high forehead, neatly trimmed beard and carefully groomed appearance matched his serious, conservative nature. Even his critics conceded that his personal qualities almost disarmed public criticism.[6]

[1] CPD, 22 May 1901, p. 143; Margaret Steven, ‘Walker, James Thomas’, ADB, vol. 12; Walker Papers, MSS 2729, K54287, K54288, K54290, K54291, SLNSW.

[2] J. T. Walker, ‘A Glance at the Prospective Finances of the Australian Federation or Commonwealth’, Proceedings, People’s Federal Convention, Bathurst, November, 1896, William Andrews & Co., Sydney, 1897, pp. 130, 134; Liberty (Fremantle), 25 February 1897, pp. 4–5; AFCD, 30 March 1897, pp. 308–315, 13 April 1897, pp. 481–482, 14 April 1897, pp. 618–619, 15 April 1897, p. 733, 22 April 1897, p. 1188; 10 February 1898, pp. 817–818; Walker Papers, MSS 2729, SLNSW; Diary entries, 30–31 March 1897, Table Talk (Melbourne), 23 April 1897, p. 9; Alfred Deakin, ‘And Be One People’: Alfred Deakin’s Federal Story, with an introduction by Stuart Macintyre, MUP, Carlton South, Vic., 1995, p. 67.

[3] Review of Reviews (Melbourne), 15 June 1898, pp. 705–707; J. T. Walker ‘To the Federal Electors of New South Wales’, Walker Papers, MSS 2729, SLNSW; CPD, 14 June 1901, pp. 1136–1137, 22 May 1901, pp. 143–144, 12 December 1901, p. 8615, 29 November 1901, pp. 8015, 8022–8023, 5 December 1901, pp. 8302–8307, 8314–8315, 6 December 1901, p. 8367–8368, 10 September 1902, pp. 15852–15853.

[4] CPD, 27 May 1903, p. 96, 23 November 1904, p. 7280, 20 October 1904, p. 5842, 24 July 1901, pp. 2914–2915, 19 December 1905, p. 7327; CPP, Reports of the committee of elections and qualifications upon the petition of Henry John Saunders, 12 July, 3 October, 11 October, 1901.

[5] CPD, 27 May 1903, p. 96; Daily Telegraph (Sydney), 30 October 1906, p. 7; SMH, 1 December 1906, p. 13, 5 December 1906, p. 10, 11 December 1906, p. 8; J. T. Walker, ‘Remarks on Some Commonwealth Financial Problems’, Commonwealth (Brisbane), vol. 1, no. 5, 3 February 1906, pp. 7–8; CPD, 14 June 1906, pp. 173–175, 13 October 1911, p. 1385, 17 September 1908, p. 45, 13 July 1910, p. 298, 24 September 1908, pp. 328–332, 26 November 1908, pp. 2295–2298, 6 July 1910, p. 52, 4 August 1910, pp. 1097–1102, 11 August 1910, pp. 1414–1418, 10 October 1912, pp. 4072–4073.

[6] Walker Papers, MSS 2729, K54288, CY845, K54290, SLNSW; J. T. Walker to Sir Ronald Munro Ferguson, Novar Papers, MS 696, NLA; Catholic Press (Sydney), 2 November 1905, p. 251.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 34-38.