HIGGS, William Guy (1862–1951)

Senator for Queensland, 1901–06 (Labor Party)

The career of W. G. Higgs, printer and journalist, was characterised by a determination to form his own beliefs and to remain constant to them. His idealism and independence, which helped to formulate the earliest policies of the Labor Party, saw him often in conflict with the Party in later years.

William Guy Higgs was born on 18 January 1862 at Wingham, a small town on the Manning River, New South Wales, where his parents kept a general store. His father, also William Guy Higgs, had migrated from St Columb, Cornwall, and his mother, Elizabeth, née Gregg, was born in Ballyconnel, County Cavan, Ireland. Higgs was the eldest of at least ten children, including nine boys. The family moved to Parramatta around 1869, and by 1875 was living in Orange, where Higgs was apprenticed to the Western Advocate as a printer.[1]

In 1882, Higgs moved to Sydney, where he worked briefly for the Daily Telegraph before commencing a four-year stint as a compositor on the Sydney Morning Herald. Soon after his arrival in Sydney, he joined the New South Wales Typographical Association and from 1886 to 1889 was its full-time, paid, secretary. During this period, he became an enthusiastic advocate of socialism. While giving evidence to the New South Wales royal commission on strikes in 1891, he recommended, as a member and a delegate of the Australian Socialist League, that ‘the State should be the sole employer of labour’ and ‘should provide everything, all the necessaries of life and all the comforts’.

Although his formal education ended at the age of thirteen, Higgs was widely read in political and social theory. He produced for the royal commission an analysis of a wide range of sources on the history and theory of socialism, including Marx, Gronlund, J. Morrison Davidson and Sidney Webb. He also provided a synopsis of the history of the English Poor Laws and Factory Acts, the Fabian essays, and the progress of socialism in England and Germany.

Though an idealist and political radical, described at various times as a ‘red ragger’, and ‘as ardent a disciple of Karl Marx as any’, Higgs advocated the achievement of social reforms through the election of labour movement supporters into government at all levels. He became secretary of the South Sydney Labor Electoral League, and in 1891 stood unsuccessfully for the Legislative Assembly seat of South Sydney. In January 1892, he attended on behalf of the South Sydney League, the first conference of the Labor Electoral League in Sydney, and was elected chairman. The conference was formative in the establishment of the Labor Party, agreeing also to open the League to women.

Higgs had made the transition from printer to journalist as owner and editor of the weekly Trades and Labor Advocate and Tribune of the People, which ran between October and December 1889. The paper was printed by his own business, Higgs and Townsend (established in 1889), which made a speciality of ‘trade societies printing’, but was dissolved in 1891. From 1890 to 1891, he edited the Trades and Labor Council paper, the Australian Workman, then returned for a period to a compositor’s frame at the Sydney Evening News.

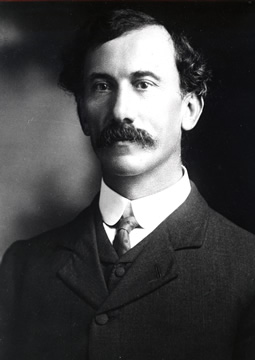

On 18 April 1889, at St Paul’s Church of England, Sydney, Higgs married Mary Ann Knight; they had two sons and a daughter. A ‘tall, well-made man, with black hair and swarthy skin’, Higgs affected a drooping moustache and black clothing, giving him a melancholy appearance which earned him the nickname of ‘the Undertaker’, reputedly coined by himself. He had a wicked sense of humour, which lent itself to teasing and sarcasm during debate, and he was fond of practical jokes; in 1914 he admitted to hiding the mace under a seat in the chamber of the House of Representatives ‘in a spirit of frivolity’.

By 1893, Higgs was invited to take over the editorship of the Brisbane Worker, even at that time Australia’s leading labour newspaper. During his editorship, from September 1893 to April 1899, the paper grew dramatically in size, circulation and influence. Regarded as a ‘forthright and fearless writer’, Higgs wrote his editorials under the slogan ‘Socialism in our time’. Higgs argued constantly for the improvement of working conditions for unionists, but also championed the causes of disadvantaged groups such as women and the aged. A highlight of his editorship was his exposure of the Queensland National Bank scandal, a ‘seething mass of rottenness and corruption’. However, his overriding theme for most of this period, graphically conveyed in savage full-page cartoons, was the destructive effect of imported labour on the economy of Queensland, and particularly on conditions for working-class people.[2]

A member of the central political executive of the Queensland Labor Party from 1895, Higgs stood unsuccessfully in 1896 for the dual member seat of Fortitude Valley in the Queensland Legislative Assembly. In February 1899, he was elected to the Brisbane City Council, and two months later he was finally elected, with his Labor colleague, Frank McDonnell, to the Fortitude Valley seat. His election prompted his resignation from The Worker; within two months he was the subject of bitter recriminations in the paper’s editorials for his failure to adhere strictly to the party line. He had voted independently of his Labor Party colleagues in opposing a motion to allow scholarships to be taken out in schools other than grammar schools. He was also at odds with many in the party over the question of Federation.

Originally suspicious of Federation, Higgs confessed in 1899: ‘I did my level best to prevent the people of New South Wales . . . from accepting the 1891 Convention Bill’. In 1893, he was instrumental in leading a crowd of Labor Electoral League supporters bent on disrupting a meeting at the Sydney Town Hall at which Edmund Barton proposed the establishment of an Australasian Federation League. But by 1899, his attitude had changed to enthusiastic support.[3]

An endorsed candidate of the Labor Party in the first federal elections of March 1901, Higgs topped the poll for Queensland Senate seats, leading Dawson and Stewart into the Senate—the largest Labor contingent from any state. Higgs was an energetic senator. Within the confines of broad Labor Party policy, he voted according to his conscience, occasionally arguing against his party colleagues. On 25 September 1901, he said ‘I support the Government only so long as they do what I think is right and proper . . .’. He was open about his republican sympathies, commenting in 1903 that ‘it would be far better for the people of England, and far better for the people of Australia, if there were a republic in both countries’.

During the protracted debate on the Customs Tariff Bill, Higgs, according to Punch, ‘manfully upheld the rights of Labour and Queensland’. When the issue of protection arose for agricultural items produced in Queensland, such as pork, tobacco, fruit and vegetables, rice, cotton-seed, tea and butter, he argued strongly for the highest possible protection. In recognition of his role during the tariff debate, he was appointed in 1905 to the royal commission on the Commonwealth tariff.

He was adamantly opposed to Asian immigration, as a threat to local labour conditions. He advocated a blanket exclusion of ‘Japanese, Chinese, Hindoos, and similar low types of humanity’, but opposed the language test for immigrants. He proposed that the 80 000 ‘coloured aliens’ already in Australia be required to pay a tax of £5 per annum, anxious that ‘we shall not make their stay in the Commonwealth too rosy’. He was vocal during the debate on the Pacific Island Labourers Bill, opposing any suggestion that Kanakas be permitted to remain in the country, and was a strong supporter of the Sugar Bonus Bill, which proposed a bonus to planters employing white labour exclusively.[4]

Higgs frequently raised points of order and questioned rulings of the President of the Senate. Appointed to the standing orders committee on 5 June 1901, he was an active member of that committee until the end of his term as a senator; and on 16 March 1904 was elected Chairman of Committees. He also served on two select committees, becoming chairman of the inquiry into the retrenchment of Major J. W. M. Carroll. Capable of rousing a crowd in his early political days, Higgs’ parliamentary speeches were clear, logical and well researched. He had a gift for verbal caricature, as when, in the Senate, he described George Reid as ‘that great political seal, who is equally at home on political land or water’.[5]

At the end of his six-year term, Higgs was held in respect by his party and his Senate colleagues, and looked set to take a strong leadership role in the next Parliament. However, confusion between the central political executive of the Queensland Labor Party and Senator Anderson Dawson saw Dawson nominate as an Independent and split the already reduced Labor vote. All the Labor candidates, including Higgs, were defeated. In Sydney, Higgs set up in business as a land agent and auctioneer, and became a director of Queensland’s government information office (1907). He was returned to the Commonwealth Parliament as a member of the House of Representatives for the central Queensland seat of Capricornia in April 1910. He held this seat until his defeat in the 1922 election.

Higgs travelled to London in 1911 to attend the coronation of George V. In July 1914, he was second to Andrew Fisher in the Caucus vote for leadership of the Labor Party. He was consistently elected to the Party’s executive, and in October 1915 was appointed Treasurer in the first Hughes administration.

Higgs was Treasurer during a difficult and turbulent time. It was becoming increasingly obvious that Australia could not meet expenditure on the war out of revenue, and would need to raise war loans. He also found Hughes’ arbitrary attitude to his Cabinet difficult to accept. On several occasions, he complained publicly about the Prime Minister’s failure to secure either parliamentary or party approval for major initiatives. Finally, in October 1916, Higgs and two other members of Cabinet, Senators Gardiner and E. J. Russell, resigned in protest when Hughes ignored the decision of the Executive Council to reject a proposal that voters at the forthcoming conscription referendum be asked to answer questions on their liability for military service with a view to their disenfranchisement if they were found to be defaulters. In a statement to the press on 30 October, Higgs said: ‘I am glad to be relieved of a position as a member of Mr Hughes’s Cabinet, which was rapidly becoming untenable’.

Higgs had indicated, in any case, that he would resign if the referendum returned a positive vote, as he was fundamentally opposed to conscription. In a letter to Fisher of 28 August 1916 he wrote: ‘I cannot bring myself to vote for compelling any man to go abroad to fight against his will, though I am in favour of compulsion for service in Australia in time of invasion or threatened invasion’.

While many of his colleagues followed Hughes out of the Labor Party, Higgs remained a member and in June 1918 was elected deputy leader of the Parliamentary Labor Party. He became a bitter critic of Hughes and his policies, but ironically was expelled from the Party in January 1920 for supporting Hughes’ referendum proposal to increase Commonwealth powers over industry and commerce. Higgs sat as an Independent until September 1920, when he joined the Nationalist Party. He was defeated as a Nationalist candidate at the 1922 election.[6]

He continued to live in Melbourne after the end of his political career. In November 1924, he was appointed chairman of the royal commission on the finances of Western Australia as affected by Federation. He became a Christian Science practitioner, and also preached in Charles Strong’s Australian Church. He was president of the Society for the Welfare of the Mentally Afflicted in Melbourne, and published a book, What Can Happen to a Man (1930), which pleaded for more humane attitudes and treatment for the insane.

Higgs died at his home in Kew on 11 June 1951 and was accorded a state funeral. He had outlived his wife and his two sons, Guy and William; only his daughter, Marie, survived him. As one of only four remaining members of the first Parliament, he had been invited to Canberra for the opening of the Jubilee Parliament, held on the day after his death.[7]

[1] CPD, 5 March 1920, pp. 228–230; H. J. Gibbney, ‘Higgs, William Guy’, ADB, vol. 9; Queenslander (Brisbane), 29 January 1898, p. 213.

[2] J. Hagan, Printers and Politics: A History of the Australian Printing Unions 1850–1950, ANU Press, Canberra, 1966, p. 77; Minutes, NSW Typographical Association, T39/1/2, Butlin Archives, ANU; H. J. Gibbney (comp.), Labor in Print, ANU Press, Canberra, 1975; D. J. Murphy, R. B. Joyce and Colin A. Hughes (eds), Prelude to Power: The Rise of the Labour Party in Queensland 1885–1915, Jacaranda Press, Milton, Qld, 1970, p. 252; Worker (Brisbane), 15 April 1899, p. 2; NSWPP, Report of the royal commission on strikes, 1891; Worker (Brisbane), 26 August 1893, p. 2; Australian Workman (Sydney), 16 January 1892, p. 3, 6 February 1892, p. 4; Bede Nairn, Civilising Capitalism: The Beginnings of the Australian Labor Party, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1989, p. 89; Australian Workman (Sydney), 10 January 1891, p. 1; Punch (Melbourne), 6 April 1905, p. 436, 13 October 1910, p. 548, 4 June 1914, p. 956;CPD, 28 May 1914, p. 1593; D. J. Murphy (ed.), Labor in Politics: The State Labor Parties in Australia 1880–1920, UQP, St. Lucia, Qld, 1975, pp. 155, 190; Worker (Brisbane), 18 June 1951, p. 6, 15 April 1899, p. 2.

[3] Murphy, Labor in Politics,p. 219; Charles Arrowsmith Bernays, Queensland Politics During Sixty (1859–1919) Years, Brisbane, A. J. Cumming, 1919, pp. 154, 158-159; Worker (Brisbane), 15 July 1899, p. 12; Murphy et. al., Prelude to Power, p. 253; QPD, 7 June 1899, pp. 312–314; Stuart Macintyre, ‘Corowa and the Voice of the People’, Papers on Parliament, December 1998, Department of the Senate, Canberra, 1998, pp. 8–9; Bulletin (Sydney), 24 June 1899, p. 9.

[4] CPD, 25 September 1901, p. 5114, 3 June 1903, p. 434; Punch (Melbourne), 13 October 1910, p. 548; CPP, Reports of the royal commission on customs and excise tariffs, 1907; CPD, 23 May 1901, pp. 242, 243, 12 December 1905, pp. 6670-6673, 6 December 1901, p. 8377, 5 March 1902, pp. 10590–10592, 18 June 1903, pp. 1089-1090.

[5] CPD, 5 June 1901, pp. 663-664, 682; Punch (Melbourne), 6 April 1905, p. 436; CPD, 25 August 1903, p. 4079.

[6] Murphy et. al., Prelude to Power, p. 238; Higgs file, ADB, ANU; CPD, 13 July 1910, pp. 362-369; Age (Melbourne), 12 June 1951, p. 3; CPD, 24 April 1918, pp. 4111-4120; Ernest Scott, Australia During the War, A & R, Sydney, 1938, pp. 352-353, 481, 505-506, 614, 618-619, 822; Age (Melbourne), 25 October 1916, p. 7, 28 October 1916, p. 13, 30 0ctober 1916, p. 9; W. G. Higgs, Letters to Andrew Fisher, 23 August 1916, 27 November 1916, Fisher Papers, MS 2919/1/233, 281, NLA; W. G. Higgs, ‘To the Electors of Capricornia’, Melbourne, 1920; Geoffrey Sawer, Australian Federal Politics and Law 1901–1929, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1956, p. 186; Argus (Melbourne), 17 September 1920, p. 9.

[7] SMH, 12 June 1951, p. 3; CPP, Report of the royal commission on the finances of Western Australia as affected by Federation, 1925; Worker (Brisbane), 18 June 1951, p. 6; Higgs file, ADB, ANU; W. G. Higgs, ‘What Can Happen to a Man’, Kew, Vic., 1930; ‘An Open Letter to the Electors of Australia’, Kew, Vic., 1937; Argus (Melbourne), 12 June 1951, p. 7; SMH, 13 June 1951, p. 2; Age (Melbourne), 12 June 1951, p. 3.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 95-99.