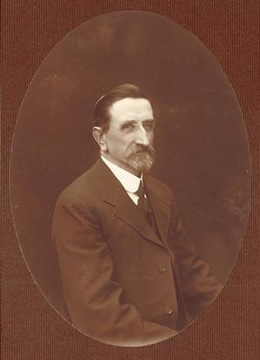

SENIOR, William (1850–1926)

Senator for South Australia, 1913–23 (Labor Party; National Labour Party; Nationalist)

On his retirement from the Senate, William Senior referred to himself as ‘that troublesome man who sat in the corner’[1]but, as we shall see, any trouble he caused was more the consequence of his conscience, than mere politicking. He was born at Holmfirth, near Huddersfield, Yorkshire, on 9 February 1850 to Thomas Senior, an engineer and farmer, and Charlotte, née Dennison. At the age of five, he came to South Australia with his parents who settled, in 1858, at Mount Gambier. Educated at the local state school, Senior was well read and had a special interest in afforestation and the geology of South Australia.

In 1873, he became a minister of the Primitive Methodist Church, his responsibilities extending to Moonta Mines, Two Wells, Woodside, Kapunda and Naracoorte. On 2 April 1878, he married Mary Trianon, née Clayton, at Mount Gambier. Senior resigned his ministry in 1883 to enter business as a storekeeper, but continued his association with the Methodist Church as a lay preacher until shortly before his death. He became well known in the Mount Gambier district, was fond of debate, especially on social and political issues, and was a foundation member of the Oddfellows’ Lodge at Orroroo. For several years, he was a leading member of local literary societies, becoming president of the Mount Gambier Democratic Association, a precursor of the Labor Party in South Australia.[2]

In May 1902, Senior unsuccessfully contested the House of Assembly seat of Victoria and Albert for the Labor Party, but then won the seat at a by-election on 25 June 1904, following the death of the sitting member. In the Assembly, Senior was to the forefront in debate on democratic reform. He pronounced that he was ‘the youngest member of the House’, and that ‘Legislative Council reform’ was ‘one of the principal planks of his platform’. Supporting the Franchise Extension Bill, he said that ‘if the people said the franchise should be lowered, it must be lowered’. He considered that political privileges ‘were embraced in manhood and womanhood, and not in possessions’. In 1910, he expressed reservations about the Aborigines Bill, which, he considered, had been constructed in the ‘spirit of compulsion’. Doubtful also about proportional representation, he spoke of ‘Miss Spence’ (the famous suffragist and proponent of proportional representation) with respect and gave his support to the Female Law Practitioners Bill in 1911. Senior was defeated at the February 1912 election, and in May 1913 was elected to the Senate.[3]

Senior’s Senate career falls into two parts, separated by the conscription issue of 1916. His speeches reveal that he brought to the debate an uprightness of character, coupled with a firm commitment to the Labor Party. He was a staunch defender of unionism, believed the Party had ‘purified’ politics and expressed pride at being a socialist. He considered that socialist ethics corresponded with Christianity and, in his early speeches, which reflected something of the English reformist Christian and socialist philosophies of the nineteenth century, expressed the view that to oppose socialism was to oppose Christianity. Senior was a frequent and, at times, pedantic speaker who seemed to relish interjections. Perhaps it was his verbosity which led Senator Oakes in the Address-in-Reply debate of May 1914 to call across the Senate chamber: ‘If you talk long enough, you will begin to believe what you say’.[4]

Conscious of the Senate’s responsibility ‘to defend the interests of the States’, Senior believed that governments should avoid debt unless they have reasonable prospects of ‘extricating themselves from it’ and that state indebtedness could be attributed to the work of the conservative side of politics. A fervent protectionist, he considered that the key to Australia’s economic problems lay in increased production and the local processing of raw materials, rather than in their export. During the Address-in-Reply of October 1914 and the budget debate later that year, he expressed the view that Australia could learn much from Germany’s socialistic management of resources. It was a theme to which he returned again in March 1920.[5]

The major crisis of Senior’s political career came during the Military Service Referendum Bill of 1916. Although the Labor Party opposed conscription and Senior himself stated that he too had always opposed it, he supported the Bill ‘against the convictions of a lifetime’. The issue that was to split the Labor Party claimed Senior as an early victim, for although he continued to consider himself a Labor man, he left the Party with W. M. Hughes and others to sit on the cross-benches as a member of the National Labor Party (later Nationalists). Senior defended his decision as a matter of personal conviction, countering taunts from his former colleagues with the argument that ‘men who will not defend society’ are not worthy to be members of it. At the May 1917 federal election, Senior was re-elected to the Senate.[6]

Following the conscription rift, Senior was critical of some key elements of Labor philosophy. For example, during debate on the Industrial Peace Bill 1920, he argued against strikes on the grounds that they caused loss of production. In discussing the Electoral Bill in 1918, he opposed both proportional representation and compulsory voting. Nevertheless, he remained an idealist and an optimist who, during debate on the Treaty of Peace in 1919, hoped that better international relations and a secure and lasting peace would be possible, despite his belief that Germany deserved to be excluded from international intercourse. On the question of the domestic economy, he continued to press for increased production as the antidote to high prices, and opposed free trade, which he felt could lower Australian living standards. He was of the opinion that the White Australia policy was inconsistent with free trade and looked to tariffs to prevent competition with ‘the products of the “slum” labour of other nations’.[7]

Senior was a lone voice in the Senate when, in 1916, he unsuccessfully opposed the amendment of the Rules Publication Act 1903. He argued against the proposed removal of two sections of the Act, which included the provision of a sixty-day period after the publication of draft regulations in the Commonwealth Gazette before such regulations became law. He protested that the Act ‘safeguarded the functions of Parliament’ and implored his fellow senators ‘not to consent to hand over indiscriminately to the heads of Departments powers so vast and far-reaching’.[8]

In 1920–21, Senior was a member of the Senate select committee which inquired into the role of Senate officials. With Senator Hugh de Largie, he dissented from the majority view that the President of the Senate had ‘absolute control’ over Senate officers, recommending instead that control should be vested in the Senate’s house committee, not the public service board. In the subsequent Senate debate, the proposal received scant support.[9]

Senior was defeated at the December 1922 election and in the following year unsuccessfully sought election to the South Australian Legislative Council as a Liberal. For the remaining three years of his life, he lived quietly in retirement. He died in an Adelaide private hospital on 22 November 1926. His wife, two sons and one of his two daughters survived him. Senior was described by Adelaide’s Advertiser as ‘a Christian gentleman’.[10]

[1] CPD, 29 June 1923, p. 514.

[2] Advertiser (Adelaide), 23 November 1926, p. 14; Register (Adelaide), 23 November 1926, p. 13.

[3] SAPD, 28 October 1904, p. 829, 5 September 1905, pp. 199–200, 13 October 1910, p. 723, 14 September 1910, pp. 501–502, 9 November 1911, p. 921.

[4] CPD, 1 October 1913, pp. 1652–1654, 20 May 1914, pp. 1087–1088, 15 May 1914, p. 1034.

[5] CPD, 28 November 1913, pp. 3601–3606, 1 October 1913, p. 1655, 15 October 1914, pp. 212–213, 16 December 1914, p. 1987, 24 March 1920, p. 662.

[6] CPD, 22 September 1916, pp. 8949–8950, 14 December 1916, p. 9803.

[7] CPD, 24 January 1918, p. 3503, 26 August 1920, pp. 3852–3853, 15 November 1918, pp. 7905–7909, 1 October 1919, pp. 12793–12803, 24 March 1920, pp. 660–663, 14 July 1921, p. 10050.

[8] CPD, 12 May 1916, pp. 7877–7878; G. S. Reid and Martyn Forrest, Australia’s Commonwealth Parliament 1901–1988: Ten Perspectives, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1989, pp. 221–222.

[9] CPP, Report of the select committee on Senate officials, 1920–21; Reid and Forrest, Australia’s Commonwealth Parliament 1901–1988, p. 425.

[10] Advertiser (Adelaide), 23 November 1926, p. 14; Register (Adelaide), 23 November 1926, p. 13.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 191-193.