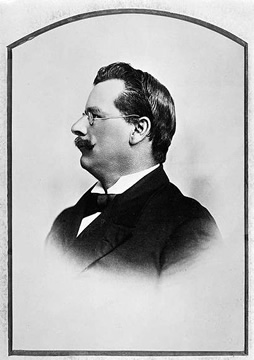

TRENWITH, William Arthur (1846–1925)

Senator for Victoria, 1904–10 (Independent)

William Arthur Trenwith, bootmaker, federal father and the first Independent senator, was born on 15 July 1846 at Launceston, Tasmania. His convict parents, William Trenwith and Beatrice McBarrett, were not wed at the time, but seem to have married by 1850. His father, who came from Penzance, Cornwall, and was transported for life for burglary, arrived in Van Diemen’s Land in 1825; he was pardoned in 1845 after a stormy penal servitude which included some four years in chains for relatively minor infractions. His mother, a governess and dressmaker, and the mother of three children, was transported for life in 1841 for ‘fire raising’ to help her Edinburgh merchant husband. She endured extended punishment in the ‘female factory’ in Launceston for offences such as insolence.

Trenwith was born while his mother was serving twelve months hard labour for ‘absconding’. She received a conditional pardon in October 1853, the year in which ‘Billy’ began work with his shoemaker father, but died in 1859. It was from his mother that Trenwith received the only book-based education of his childhood. Unable to accept a stepmother, he left home, taking his ten-year-old brother with him. He joined the Launceston Working Men’s Club, where he learned boxing, debating, and the importance of self-education, and at seventeen was elected to its provisional committee. At nineteen, he was Hobart lightweight boxing champion and a strong public speaker. On 2 November 1868, he married Susannah Page at St John’s Church of England, Launceston, according to the rites of the United Church of England and Ireland. In the same year, he moved to Victoria, where he set up in the boot trade in Carlton and became involved in local political and industrial affairs.[1]

Trenwith carried the lessons of his early years close to the surface. Quick-tempered and mixing radical reformist zeal with down-to-earth pragmatism, he was fast with fists and tongue and was to be involved in litigation on more than one occasion in the years ahead. Lacking formal schooling, he possessed a range of other attributes: stentorian voice, powerful physique, a strong will, a logical, pragmatic mind, a capacity for learning from observation and experience, and a natural flair for debate. Fiercely outspoken in his commitment to industrial and political reform in his early public life, over time he exhibited a growing taste for respectability. By 1878, he was active in the Berry reform movement. His trade unionism gathered momentum after he chaired the founding meeting of the Victorian Operative Bootmakers’ Union in May 1879, and in 1883 he became secretary. The bootmakers’ lockout and strike of 1884–85 saw him emerge as a major labour figure. His accession to the presidency of the Melbourne Trades Hall Council (THC) in 1886 marked the triumph of a more militant unionism over the old guard, though the 1890 maritime strike led him to favour compulsory arbitration to direct action.In these years, he won a reputation as a powerful orator, a shrewd organiser and an effective industrial activist whose militancy alarmed employers and whose temperament earned him enemies within his own camp. By 1889, he had developed politically as a lecturer/organiser with the liberal National Reform League (NRL) and industrially through militant trade unionism. In the NRL, he campaigned for land tax, reform of the Legislative Council and protective industry tariffs. Protection was, and would remain, the central concern of his public life.

While Trenwith maintained a prominent industrial role through the 1890s, parliamentary politics became increasingly important and revealed a growing gap between himself and parts of his labour constituency. While he had urged labour to pursue independent parliamentary representation (he had become Treasurer of the THC’s Parliamentary Committee in 1884), it is not clear that he supported an independent labour party at this point in his career. In 1879, he contested the seat of Villiers and Heytesbury as a Liberal and, in 1886, Richmond for the National Liberal League. Moreover, he undertook tasks that suggested he was seeking a broader acceptance. For example, he was appointed a commissioner of the Adelaide Jubilee Exhibition in 1886 and was accorded a similar role in Melbourne’s Centennial International Exhibition of 1888.[2]

On 7 April 1896, soon after losing his first wife, he married Elizabeth Bright and travelled extensively in England, Scotland, Ireland and Europe. The trip, funded by supporters, enabled him to have a successful operation to remove a cataract in one eye. While in London, he addressed a workers’ meeting at Battersea, the electorate of John Burns, the British labour leader. During the 1890s, Trenwith had acquired a 1200 acre estate in the Victorian Mallee.[3]

Trenwith was elected as the only Labor representative to the Australasian Federal Convention of 1897–98 and became a member of the Convention’s constitutional committee. Alfred Deakin considered that he ‘exercised a considerable influence because he was not simply a brilliant delegate but distinctively the representative of the working classes’. During the debate on whether universal franchise should be included in the Constitution, Trenwith suggested wording which became part of section 41 of the Constitution and which helped to pave the way for female suffrage early in the new Federal Parliament.[4]

Trenwith’s political career proper had begun in 1889 when he was elected to the Victorian Legislative Assembly as the Member for Richmond. As the first labor representative in Parliament, he was initially an aggressive, blunt speaker. He advocated education for the working class, protection and measures to reduce unemployment.He repeatedly moved for the introduction of the eight-hour working day. Over time, according to Deakin, he developed a more polished speaking style and became an outstanding debater. He served on the royal commissions on constitutional reform (1894) and on the factories and shop law of Victoria (1900). However, his credibility as a working class representative was an issue that dogged his industrial and political career as he persistently sought accommodation with the liberals in an era of growing separation between liberal and labour politics.[5]

Despite his continuing THC ties and his emergence as the unofficial leader of the small Labor presence in the Legislative Assembly, throughout the 1890s he refused repeatedly to pledge himself to an independent Labor Party platform. His liberal ties had been reflected in the name given in 1894 to the new parliamentary Labor grouping, the ‘United Labor and Liberal Party’. By 1896, this had become the United Labor Party. Trenwith was attacked for supporting the Liberal leader, Sir George Turner, in the 1897 election, and for his role in the Federal Convention, seen by Labor as essentially conservative. In November 1900, Trenwith attended a meeting organised by Deakin to create a unified liberal organisation. He relinquished the leadership of the Parliamentary Labor Party following his inclusion in the short-lived Turner Ministry (1900–01) as Commissioner of Public Works, Minister of Railways, and Vice-President of the Board of Land and Works. In the Peacock Ministry that followed, he held the posts of Chief Secretary, Minister of Railways and Vice-President of the Board of Land and Works.[6]

Out of ministerial office in June 1902, and under attack from sections of the labour movement, he turned his attention to the Commonwealth Parliament. In 1903, riding a wave of public sympathy concerning earlier treatment by the Age for alleged extravagance as railways minister, Trenwith, standing as an Independent, topped the poll for the Senate in Victoria. Soon after, he partially lost his sight following another cataract operation. He remained in the Senate, occupying a prominent seat due to his visual disability, until his electoral defeat in 1910. Trenwith served on the standing orders committee for the whole of his period in the Senate and his contributions to debate focused on many of the matters that had concerned him throughout his political life. Protection continued to be the lynchpin, and pragmatism his guiding principle. While experience had long since removed the rough edges from his parliamentary performances, he remained bedevilled by the tension between his labour movement origins and his increasingly apparent liberal commitment.[7]

Trenwith’s first Senate speech addressed the siting of the proposed federal capital. However, as a strong federalist, he used it also to provide an indication of the development path he favoured for the new nation: improved communication and transport to facilitate decentralisation, development and better imperial ties; the inclusion of a port in the federal territory to ensure that the new capital would be directly in contact with the outside world; vigorous promotion of the rights of the Commonwealth as well as the legitimate rights of the States; avoidance of a freehold land system in the capital territory in order to block land speculation; and the importance of protection for Australian industry development which, in turn, was necessary to ensure Australia’s security. In the years that followed, he was committed to a federation which would foster the agricultural and industrial growth required to underwrite the emergence of a self-confident Australian nation, suggesting in 1906, that a strong Federal Parliament would be more likely than the existing state legislatures to ‘regard the rights of the public’. Remaining an ardent protectionist, he contributed persistently to the tariff debate. In 1905, speaking on the Copyright Bill, and possibly reflecting on the criticism of him by the Age, he argued against press concentration, this ‘vicious, baneful combine’, which, he held, was seeking to dominate cable news in Australia on behalf of a small number of newspapers. In 1909, however, with an election to face as a Fusionist, he was somewhat circumspect in his comments about the press, arguing that it represented a warehouse of information.[8]

Trenwith was more consistent in his attitude to White Australia. Although he shared the racial prejudices of his time, his concern was essentially the pragmatic one of defending wages and conditions. Declining to support the more offensive statements of the policy, in 1909, in response to a Labor amendment which sought to exclude ‘coloured’ residents from eligibility for invalid and old-age pensions, he restated his views: ‘the main charge against . . . our White Australia policy is that it is inhuman’. In 1906, during debate on the Australian Industries Preservation Bill, he revealed a wide circle of close acquaintances among Australian industrialists and eulogised in particular H. V. McKay, the agricultural implement maker, whom, he said, he had known for twenty years. He spoke frequently against both Australian and foreign trusts and combines and was an advocate of public enterprise. During debate on the Manufacturers Encouragement Bill 1908, he argued vigorously for the establishment of an iron and steel industry for defence reasons, but he indicated that his preference was for nationalised industry.

Trenwith, despite his visual disability, was skilful in clarifying the terms and purpose of debate. However, he was rarely original. Deakin’s description of him seems apt:

‘Master of a sledge-hammer style of oratory, very loud, very forcible and very logical, he softened away its excrescences of violence, watched and studied . . . and gradually elbowed his way . . . into the front rank of . . . debaters. There were few adornments and few quotations in his speeches, the material for which he found largely in the addresses of those to whom he replied and for the rest drew out of his own recollection. If he had pursued his course of self-education as consistently in his later years as in his earlier, and if he had added a deeper knowledge of books to the knowledge of affairs which he acquired, he might have outshone all his associates’.[9]

Throughout his time in the Senate, Trenwith wore the hostility of his former Labor colleagues without complaint, though this became more difficult as his personal commitment to Deakin deepened. During the Address-in-Reply in 1907, he spoke glowingly of Deakin’s performance at the Imperial Conference. In 1909, as a ‘Deakinite liberal’, Trenwith expressed confidence in Deakin, but doubted whether the conservatives would follow a liberal agenda, and, in negotiations over the formation of the Fusion Government, finally voted against the union. In the Senate, however, he sat with the new Government’s members to the extreme irritation of Labor senators, who repeatedly attacked him for what they saw as a final betrayal. He defended himself, arguing that ‘my sympathies during the whole of my political life have been with the aspirations of the Labour party’. He explained that the party with which he was associated in Victoria, the ‘Democratic party’, had withdrawn its support for the Fisher Labor Government against his wishes.

In the 1910 federal election, Trenwith was one of three Fusionist candidates to contest the Senate ticket in Victoria. Deakin’s party was routed, and Trenwith’s defeat ended his parliamentary career. He attempted to re-enter the State Parliament in 1911 when he contested the seat of North Gippsland. He tried again for the Federal Parliament in 1913 and 1914, firstly for the House of Representatives seat of Denison in Tasmania, and secondly for the Senate for Victoria.On each occasion he represented the Liberals and on each he was unsuccessful.[10]

On 26 July 1925, Trenwith died at his home in Staughton Road, Camberwell, Melbourne. Trenwith’s second wife had died in 1923. On 1 October 1924, at Echuca, he married Helen Florence Sinclair who survived him. Of the three sons and daughter of his first marriage only one son, William, survived him. Of his second marriage, two sons, Arthur and Edward, survived him, a daughter having predeceased him. Trenwith’s death certificate gave his occupation as ‘Gentleman’. His estate was probated at £7675 and included nine cottages in Richmond as well as his Camberwell home. The sole beneficiary was his third wife, Helen.

The Bulletin described him as ‘a giant’ compared with some of his Labor successors in the Victorian Parliament, but noted that his deeds were ‘forgotten or only vaguely remembered’ and that only a few old political friends, all liberals, were at the graveside: ‘Labor stood aloof’.[11]

[1] Letter, Anne Rand to Dr D. Langmore, 19 December 1988, Trenwith file, ADB, ANU; Bulletin (Sydney), 31 December 1903, pp. 8–9; Bruce Scates, ‘Trenwith, William Arthur’, ADB, vol. 12.

[2] Punch (Melbourne), 11 May 1905, p. 604; J. Norton, The History of Capital and Labour in All Lands and Ages, Oceanic Publishing Co., Sydney, 1888, pp. 157–168; Graeme Davison, The Rise and Fall of Marvellous Melbourne, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1978, pp. 62–63; This phase of Trenwith’s career has been well covered in Scates, ‘Trenwith, William Arthur’, ADB; D. J. Murphy (ed.), Labor in Politics: The State Labor Parties in Australia 1880–1920, UQP, St Lucia, Qld, 1975, pp. 296–306; Bruce Scates, ‘“Wobblers”: Single Taxers in the Labour Movement, Melbourne 1889-1899, Historical Studies, vol. 21, October 1984, pp. 174–197.

[3] Australasian (Melbourne), 25 April 1896, p. 800, 10 October 1896, p. 707; British Australasian (London), 3 September 1896, pp. 1456–1458, 1 October 1896, p. 1630; Bulletin (Sydney), 13 October 1900, p. 13.

[4] Alfred Deakin, ‘And Be One People’: Alfred Deakin’s Federal Story,with an Introduction by Stuart Macintyre,MUP, Carlton South, Vic., 1995, p. 72; B. Wise, The Making of the Australian Commonwealth 1889–1900, Longmans, Green, and Co., London, 1913, pp. 220–221, 230–231, 339–343, 347–348;Ann Millar, ‘Feminising the Senate’, in Helen Irving (ed.), A Woman’s Constitution? Gender & History in the Australian Commonwealth, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1996, pp. 131–132; AFCD, 15 April 1897, pp. 722–729.

[5] John Rickard, Class and Politics: New South Wales, Victoria and the Early Commonwealth, 1890–1910, ANU Press, Canberra, 1976, p. 28; Janet McCalman, Struggletown: Portrait of an Australian Working-Class Community, Penguin Books, Ringwood, Vic., 1988, p. 38; Punch (Melbourne), 11 May 1905, p. 604; Deakin, ‘And Be One People’, p. 72; VPP, Report of theroyal commission on constitutional reform, 1894.

[6] Tocsin (Melbourne), 20 October 1898, p. 2; McCalman, Struggletown, p. 38; Tocsin (Melbourne), 28 July 1898, p. 5; Murphy, Labour in Politics, pp. 300–306; J. A. La Nauze, Alfred Deakin: A Biography, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1965, vol. 1, p. 223n.

[7] Table Talk (Melbourne), 21 November 1901, p. 4; W. A. Trenwith, Extracts from the Syme‑Trenwith Controversy, Asher and Co., Richmond, Vic., 1902; Punch (Melbourne), 24 December 1903, p. 847; Bulletin (Sydney), 31 December 1903, pp. 8–9.

[8] CPD, 2 June 1904, pp. 1866–1872, 1878–1879, 1892, 3 June 1904, pp. 1961–1962, 1969–1972, 1977–1984,25July 1906, pp. 1719, 1734–1755, 28 September1905, p. 2940, 21 October 1909, pp. 4826–4827.

[9] CPD, 6 February1908, p. 7871, 6 August 1909, p. 2164, 15 August 1906, pp. 2819–2832, 2 October 1906, pp. 5833–5846, 27 November1908, pp. 2362–2363; Punch (Melbourne), 11 May 1905, p. 604; Deakin, ‘And Be One People’, pp. 71–72.

[10] CPD, 11 July 1907, pp. 376–378,30 June 1909, pp. 571–581; Henry Gyles Turner, The First Decade of the Australian Commonwealth,, Mason, Firth & McCutcheon, Melbourne, 1911, pp. 215–216; La Nauze, Alfred Deakin, vol. 2, pp. 562–564, 600n; Punch (Melbourne), 7 April 1910, p. 464.

[11] Trenwith file, ADB, ANU; Bulletin (Sydney), 6 August 1925, p. 20; Argus (Melbourne), 28 July 1925, p. 10; Labor Call (Melbourne), 30 July 1925, p. 7.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 296-301.