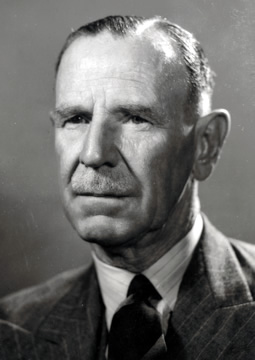

WORDSWORTH, Robert Hurley (1894–1984)

Senator for Tasmania, 1950–59 (Liberal Party of Australia)

Wordsworth was an outstanding horseman and at the conclusion of the war chose to continue his army career with a cavalry regiment in the Indian Army. He was discharged from the AIF in October 1917, and posted to the 16th Cavalry (the 6th Duke of Connaught’s Own Lancers from 1922). He served in two campaigns on the North-West Frontier of India (1919-20 and 1930), and was promoted lieutenant colonel in 1939. During his Indian postings he had opportunities to pursue sporting interests; he was a fine polo player and trained Waler horses, went pig sticking, snipe shooting and fishing. The latter was a recreation he shared with his Tasmanian-born wife, Margaret Joan, daughter of Walter Ross‑Reynolds and his wife, Helen. Margaret and Robert met when Robert was playing polo in Australia, and were married at St David’s Cathedral, Hobart, on 5 September 1928. Margaret accompanied him to India where social activities as well as military responsibilities were frequent in the years between the wars. During World War II, Wordsworth commanded the Risalpur Cavalry Brigade and, from 1942, the 31st Indian Armoured Division. He was later appointed Major-General, Armoured Corps at General Headquarters, New Delhi. Mentioned in despatches, Wordsworth was appointed CBE in 1943 and CB in 1945.[2]

Wordsworth retired from the Indian Army in 1947 and he and his wife settled on a farm on the Meander River, near Westbury in northern Tasmania. When invited to stand at the state election of 1948 as a Liberal candidate for the chiefly rural electorate of Wilmot (now Lyons), he accepted. He later confided in his memoir: ‘It was very brash of me to even entertain the idea of entering politics, but I was full of confidence, and of ignorance too’. His kindly mentor was Angus Bethune (later Sir Angus and Liberal premier of Tasmania) and Wordsworth came close to success. With the 1949 federal election coming up, Wordsworth turned down a suggestion that he stand for the House of Representatives but agreed to attempt the Senate, and was successful. His term of service commenced on 22 February 1950, and in accordance with the legislation governing the expansion of the Senate from thirty-six members to sixty, would have concluded on 30 June 1953. In the event, the federal Parliament’s second simultaneous dissolution intervened and an election was called in April 1951. Wordsworth only narrowly avoided defeat, and, as a consequence of his place in the poll, became a three-year term senator once again. He was more successful at the 1953 election, being elected first among the Liberals. As a senator, Wordsworth was conscientious in his attendance at sittings and divisions, his committee service including membership of the prestigious Joint Committee on Foreign Affairs. He led the Australian delegation to the 46th conference of the Inter-Parliamentary Union, held in London in 1957, and was one of two Australian representatives on the Inter-Parliamentary Council from 1957 to 1958.[3]

Wordsworth considered his ten years as a senator the unhappiest of his life, ‘soldiering’ having been his profession. ‘A soldier’, he wrote, ‘is trained to be concise in speech and to act quickly and decisively’ while a ‘politician must be a talker above all else’. He admitted that he was only really interested in two subjects, external affairs and defence, and came to ‘abhor uninformed criticism, particularly in debate’. He believed, however, that he was elected on a party platform and to represent his state, so took an interest in, for example, the shipping and timber industries as they directly affected Tasmania, though on one occasion he voted against his party by refusing to support a pay rise for politicians.[4]

Wordsworth, who consistently advocated increasing the strength of the armed forces, defined Australia’s role in the western alliance in terms of the need to oppose the spread of communism, particularly in Asia. One aspect of this was his support of the British atomic weapons program, including the tests conducted at Monte Bello and Maralinga. Another was a willingness to participate in regional defence pacts (ANZUS, SEATO), while a third was his support of economic assistance to emergent nations, thereby removing the underlying causes of popular discontent. For example, he supported the Colombo Plan (but was critical of the failure of the Australian Government to exploit the propaganda value of Australian aid).[5]

During his decade in the Senate, Wordsworth sat alongside John Gorton, observing that Gorton was both a hard worker and ambitious, but that he had never considered him ‘Prime Ministerial material’. Wordsworth admitted that he made more friends among the Country Party members than among other politicians and was particularly delighted to find that a great friend from Gallipoli days, Albert Reid, had been elected as a Country Party senator for New South Wales. In Canberra Wordsworth and Reid became known as ‘the twins’. Wordsworth believed that he was well liked and that this was partly due to his having reached in the army the top of his profession, and because he was not seeking political publicity or a ministry. Be that as it may, his popularity with the electorate was not sufficient to prevent his defeat at the 1958 election. He seems to have been somewhat consoled by a dinner given in his honour by parliamentary colleagues at the expiration of his term in 1959.[6]

Electoral defeat, however, was not the end of Wordsworth’s career. He was party president of the Tasmanian Liberal Party from 1960 to 1962, and served as Administrator of Norfolk Island from June 1962 to August 1964. In conjunction with the Minister for Territories, Paul Hasluck, Wordsworth conducted negotiations with the Norfolk Island Council, culminating in the passage of new legislation defining the island’s system of government. As administrator, Wordsworth appears to have been popular and effective. Returning from a visit to Norfolk Island in 1963, Gough Whitlam told the House of Representatives: ‘I should like to testify to the respect and esteem in which Major-General Wordsworth, a former senator, is held by the people whom he rules. His experience in command and administration stand this country and that island in very good stead’.[7]

Wordsworth returned to Tasmania, living in and around Launceston until finally settling at Longford, where he enjoyed fly-fishing. President of the Launceston Club (1967-69), he was also honorary colonel of the Tasmanian military cadets. Robert Hurley ‘Wordy’ Wordsworth died, at the age of ninety, on 23 November 1984, at Longford, his widow receiving the sincere condolences of a Parliament he had left twenty-five years before. He was survived also by his son, David John, and his daughter, Mary Ana (Mrs Scarf). A funeral service was held on 27 November at Christ Church, Longford, followed by a private cremation. The eulogy recorded that ‘he was outstandingly a man of service’ and that his ‘kindliness and innate friendliness found constant expression in acts of service; and his influence was always for good’.

David was a Liberal MLC in Western Australia (1971-93) and a minister in the Court Government (1977-82), who married Marie Louise Johnston, the daughter of E. B. Johnston.[8]

[1] Wordsworth, born Robert Harley, used this form of his name at least until the time of his marriage. He became Robert Hurley at some time before his return from India in 1947; R. H. Wordsworth, Memoirs, chapter entitled ‘To Parliament’, p. 7 (unpublished manuscript in possession of Wordsworth’s daughter, Mrs A. Scarf).

[2] Examiner (Launc.), 26 Nov. 1984, p. 25; Wordsworth, R. H.—War Service Record, B2455, NAA; Reveille (Syd.), 1 June 1938, p. 26; Address of Brigadier the Rev. R. J. Barham at Wordsworth’s funeral (in possession of Mrs A. Scarf); CPD, 6 June 1950, p. 3679, 26 May 1955, p. 485.

[3] Wordsworth, Memoirs, chapter entitled ‘To Parliament’, pp. 1-2, 6; Examiner (Launc.), 28 Aug. 1948, p. 5, 13 Dec. 1949, p. 3, 18 May 1951, p. 3, 28 May 1953, p. 3; J. R. Odgers, Australian Senate Practice, 6th edn, Royal Australian Institute of Public Administration, Canberra, 1991, p. 25; CPP, Report of the Australian delegation to the forty-sixth conference of the Inter-Parliamentary Union, London, 1959; Examiner (Launc.), 5 Dec. 1958, p. 4.

[4] Wordsworth, Memoirs, chapter entitled ‘To Parliament’, pp. 7-8; CPD, 26 June 1951, pp. 335-6, 12 July 1951, pp. 1459-60, 22 Mar. 1956, pp. 384-6, 26 Mar. 1958, pp. 359-60, 1 May 1958, p. 717, 21 Aug. 1958, pp. 159-60, 31 May 1956, pp. 1176-7; Senate, Journals, 31 May 1956.

[5] CPD, 1 Mar. 1950, p. 189, 1 Mar. 1956, pp. 230-2, 11 Aug. 1954, pp. 163-5, 28 Apr. 1955, pp. 110-14, 19 Oct. 1954, pp. 847-8, 9 Nov. 1954, pp. 1282-5, 3 Apr. 1957, p. 318.

[6] Wordsworth, Memoirs, chapter entitled ‘To Parliament’, pp. 5, 8.

[7] Katharine West, Power in the Liberal Party: A Study in Australian Politics, F. W. Cheshire, Melbourne, 1965, p. 189; Letter, Wordsworth to Secretary, Department of Territories, 19 Dec. 1963, A452, 1962/3244, NAA; CPD, 29 Oct. 1963 (R), p. 2413; Merval Hoare, Norfolk Island: An Outline of Its History, 1774–1981, UQP, St Lucia, Qld, 1982, pp. 136-8; CPD, 29 Oct. 1963 (R), p. 2414.

[8] Examiner (Launc.), 26 Nov. 1984, p. 25, 24 Nov. 1984, p. 21; CPD, 21 Feb. 1985, pp. 26–31; Address of Brigadier the Rev. R. J. Barham.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 2, 1929-1962, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic., 2004, pp. 225-227.