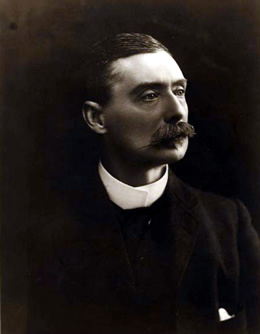

DRAKE, James George (1850–1941)

Senator for Queensland, 1901–06 (Protectionist)

As one of two ministers in the first Senate, James George Drake established the largest of the seven new Commonwealth departments—that of Postmaster-General. Born in London on 26 April 1850, son of Edward Drake, a publican, and his wife, Ann Fanny, née Hyde, Drake was educated at King’s College School, London. Eager to see the world, he left London on the Abbey Holmeon 4 October 1873, arriving in Brisbane on 14 January 1874.

Employment in southern Queensland’s Stanthorpe tin mines eluded him, but he found work as a clerk in stores at Toowoomba and Brisbane. Drake jackarooed in western Queensland before becoming a journalist on two provincial city newspapers (the Bundaberg Star and Rockhampton’s Daily Northern Argus) and the state’s two metropolitan dailies, the Brisbane Courier—as leader writer—and the Telegraph. Drake then moved to Melbourne, and worked as an Argus parliamentary reporter. Developing a lifelong interest in politics, he returned to Queensland as a Hansard reporter, while studying law. He was admitted to the Queensland and Victorian Bars in 1882, and within five years had established a lucrative practice in Brisbane.

Drake entered Queensland politics in 1888 as MLA for Enoggera, holding the seat until 1899. He was a Protectionist, a believer in a White Australia, and an opponent, for fluctuating reasons, of Kanaka labour. He espoused these causes in the radical Boomerang, which he co-founded and co-edited with William Lane (1887-90), and Progress (1899-1901).

Drake was an enthusiastic federationist, who chaired the Queensland Federation League, and declared as early as 1888 that ‘the federation and future independence of Australia is inevitable . . . I look forward to its advent without fear or misgiving’. In Federation: Imperial or Democratic, a collection of his articles, he proposed that the major impetus for Federation should derive not from Great Britain—the argument of Australia’s Imperial Federation Leagues—but from Australian popular sentiment. He dismissed the 1891 National Australasian Convention as ‘the natural outcome of the deliberations of a little body of self-elected notables’. There is no truth in Punch’s claim that Drake’s was the decisive vote in securing the passage of Queensland’s Australasian Federation Enabling Bill (June 1899), which allowed Queenslanders to decide the federal question at a referendum held the following September. Respected by leading figures in the federal movement such as Edmund Barton—who sought his advice on how to smooth the passage of the Commonwealth of Australia Bill through the Imperial Parliament—Drake was also adept at communicating the federal message, taking ‘federation from the floor of the House to the streets and public halls’.

In 1899, frustrated by years in opposition (he led the Independent Opposition in the Legislative Assembly, 1896-99) Drake accepted Premier Robert Philp’s offer of a seat in the Legislative Council, the leadership of the Council and the portfolios of Postmaster-General and Secretary for Public Instruction.[1]

Following the death, after a week in office, of Australia’s first Minister for Defence, Sir James Dickson, Drake said yes to Prime Minister Edmund Barton’s offer—made through Philp—of the portfolio of Postmaster-General in the first Commonwealth ministry. Under section 64 of the Constitution, with other members of the first federal ministry, he held office before his election to the Senate—as a Protectionist on 30 March 1901.

In his first Senate speech on 31 May 1901, Drake called for the abolition of Kanaka labour and the humane repatriation of Kanakas, although his critics thought him more interested in increasing white employment in the sugar industry than alleviating the Kanakas’ plight. In debate on the Public Service Bill, Drake supported the appointment of a public service commissioner and a public service board to reduce political influence and overstaffing in the Commonwealth public service.

Drake urged the appointment of more judges to the High Court to strengthen the institution and reinforce public perceptions of it. He envisaged the Court as Australia’s final appellate body in preference to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. Drake objected when the Government rushed legislation through the Senate, and opposed the cavalier attitude of governments to the Senate standing orders, exemplified in their readiness to suspend them. On 11 September 1906, he argued vigorously against the suspension proposed by J. H. Keating on the grounds that inadequate time had been allowed to debate the Constitution Alteration (Senate Elections) Bill.[2]

As Postmaster-General, Drake’s principal task was the creation of a uniform national post and telegraph system, whose foundations were laid by the Post and Telegraph Act 1901. In his second reading speech on the Bill in June 1901, Drake set out his views on the Commonwealth as ‘a Government of the true federal type’, insisting that no state in such a union should receive preferential treatment in post and telegraph services. Drake also emphasised the advantages of a publicly owned telegraph service over one operated by a private proprietor. Drake’s appointment of Robert Scott as head of the Postmaster-General’s Department proved a judicious one, and, although the fledgling organisation was criticised—the Age reported a number of administrative problems—Drake’s stewardship of the portfolio appears to have been sound.

While Minister for Defence for six weeks in 1903, he continued the work begun by his predecessor, Sir John Forrest, of seeing the Defence Act through Parliament. As Attorney-General, Drake led successfully in D’Emden v. Pedder, the High Court’s first major constitutional case, which prevented the collection of state stamp duty on salaries paid by the Commonwealth, and enumerated the limits to Commonwealth legislative power in relation to the states and vice versa.[3]

Drake acted as Senate leader during R. E. O’Connor’s frequent absences to attend to his Sydney law practice. When concern arose among senators in 1903 that insufficient legislation was being initiated in the Senate, Drake, as de facto leader, discussed the matter with the Prime Minister, Sir Edmund Barton, who replied to Drake by letter on 31 May 1903:

The Senate is always touchy if it seems to have too little work promised to it, and I hear talk … of their merely ‘marking time’ with nothing before them but the S. O. [Standing Orders] and the Senate Elections Bill. There being so many Bills which we can’t begin in your House, the question what we can bring in there is acute. . . . If I can shear the Nationalisation Bill of any expenditure provisions I shall do so, and give it to you—but say nothing until I have gone through it again. It will be difficult to frame a Patents Bill successfully without providing for some expenditure, but I live in hope.

No longer a minister after July 1905, Drake remained active in debates. Punch observed that:

Senator Drake has become part and parcel of the Senate. One cannot imagine that Chamber without his dapper frock-coated figure, pince-nez between the right thumb and forefinger, the left hand holding a handkerchief, his eyes blinking nervously, and seeking inspiration from the chandelier, his voice pouring out equably, soft, soothing, stoical’.

In 1906, while still a senator, Drake founded the broadsheet Commonwealth, to counter strong anti-federal feeling in Queensland. He intended it as a platform from which to re-emphasise the founders’ federal philosophy, which he thought was being eroded by over frequent calls for constitutional change as a substitute for addressing political problems through parliamentary discussion and compromise. Drake also hoped to strengthen the conservative vote in the 1906 general election. In its first issue, Drake confidently told readers:

Commonwealth is the direct lineal successor to Boomerang and Progress. Boomerang first inspired the desire for nationality in Queensland. Progress advocated Federation and the adoption of the most liberal democratic constitution in the world. Commonwealth defends the Commonwealth against all attacks, and is LOYAL to the Constitution.

However, Drake was already disillusioned with much of the great Commonwealth experiment:

We must . . . go back to the first Parliament and the first administration. That was the period of initiative, of life and energy. The rest has been a continuous tailing off, like the highway that becomes a road and then a track, a path, and finally runs up a tree. That’s about where we are now, and we want to see the Commonwealth back on the safe, broad highway.

The paper was boycotted, and Drake’s fortune’s worsened with the loss of his preselection. He decided not to stand as an Independent at the forthcoming poll and this marked the end of his political career.[4]

Drake left politics with a measure of relief, happy to be free of the exhausting land and sea travel, and eager to return to the Queensland Bar, mainly for financial reasons. Nevertheless, he missed politics, and remained proud of the achievements of the first Commonwealth Parliament, recalling ‘how subsequent events have justified the work of the first Federal Parliament and vindicated its members’. He failed to win the Queensland Legislative Assembly seat of Brisbane North as an Independent Liberal in 1907. His political life over, Drake concentrated on his law practice until appointed a state crown prosecutor (with the right to private practice) in 1910. In 1912 and 1915 he served as an acting district court judge. The state Labor Government retired him on grounds of age in 1920. Drake, almost certainly Queensland’s oldest legal practitioner, practised at the Bar until he was ninety–one.

Drake had a superb memory and an exceptional knowledge of English literature. A major in the Queensland Defence Force and a long-time member of Brisbane’s Johnsonian Club, Drake served also as a councillor of the Royal Society of St George and a vice-president of the Brisbane branch of the English-Speaking Union.

On 25 June 1897, Drake, a member of the Church of England, had married in a Baptist ceremony, Mary, daughter of Abraham Street of Brisbane. Drake died in the Brisbane General Hospital on 1 August 1941 and was buried in Toowong Cemetery. His children—one son, James, and three daughters, Trevers, Constance and Alexia—survived him. Mrs Drake predeceased him in 1924. Since 1935, Drake had been the last surviving member of the first Commonwealth ministry. Although he made a notable contribution to public life, Drake remained modest about his achievements, reflecting that ‘if I have not been exactly a maker of history, I have at least enjoyed an inside view of the process of history-making’. A relative of Drake’s, by marriage, has testified to his probity: ‘When he retired as postmaster-general, in recognition of his work Mr Drake was offered a complete set of all Australian stamps to that time. He accepted, but on condition that each stamp was marked “specimen copy only” as he felt the gift would have been too valuable otherwise’.[5]

[1] QPD, 6 July 1897, pp. 209-210, 8 June 1899, pp. 328-332; Brisbane Courier, 23 March 1888, p. 2; James G. Drake, Federation, Imperial or Democratic, Benjamin Woodcock, Brisbane, 1896, p. 12; Letter, Edmund Barton to J. G. Drake, 2 January [1900], Drake Papers, MS 6305, NLA; W. R. Johnston, The Role of the Legal Profession in Queensland in the Federation movement, 1890-1900, MA Qual. thesis, University of Queensland, 1963, p. 88; Alcazar Press (comp.), Queensland 1900, Wendt, Brisbane, 1900, p. 159.

[2] Brisbane Courier, 26 March 1901, p. 4, 27 March 1901, p. 4, 29 March 1901, p. 4; CPD, 31 May 1901, pp. 541-549, 4 December 1901, pp. 8245-8246, 8278, 8279, 1 August 1901, pp. 3348-3351, 22 August 1906, pp. 3187-3188, 11 September 1906, pp. 4276-4278, 21 September 1906, p. 5075.

[3] CPD, 6 June 1901, pp. 749, 762-763; Age (Melbourne), 21 August 1901, p. 5; CPD, 2 October 1901, pp. 5418-5423; D’Emden v. Pedder (1903–04) 1 CLR 91; Colin Howard, Australian Federal Constitutional Law, Law Book Company, North Ryde, NSW, 1985, pp. 144-147.

[4] Letter, Sir Edmund Barton to J. G. Drake, 31 May 1903, Drake Papers, MS 6305, NLA; Punch (Melbourne), 30 March 1905, p. 404; Commonwealth (Brisbane), 6 January 1906, pp. 2, 11; Letter, J. G. Drake to Sir Josiah Symon, 9 January 1907, Symon Papers, MS 1736, NLA.

[5] Sound Recording of J. G. Drake, [1940], TRC 85, NLA; J. G. Drake, ‘Random Recollections: Past and Future, No. 1’, Drake Papers, UQFL 96, Fryer Library, University of Queensland; Betty Newell and Rodney Thelander, Footprints: Life and Times of Charles Thelander 1883–1959, Watson Ferguson, Brisbane, 1995, p. 129; CPD, 20 August 1941, pp. 4-5, 6-7; H. J. Gibbney, ‘Drake, James George’, ADB, vol. 8.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 85-88.