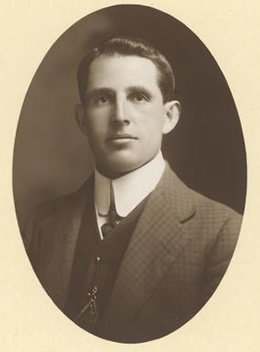

READY, Rudolph Keith (1878–1958)

Senator for Tasmania, 1910–17 (Labor Party)

Rudolph Keith Ready, draper and businessman, was born at Latrobe, Tasmania, on 15 December 1878, the son of Samuel, a saddler, and Mary Minnie Susanna, née Mumford, who were pioneers of the Latrobe district. After a primary school education, Ready studied at the Latrobe Commercial College and worked as a junior in a drapery store. At the age of nineteen, he was employed by Button Brothers to conduct their business in Campbell Town, becoming their store manager. On 23 September 1901, he married, in the Wesleyan Church at Campbell Town, Vida Constance, née Lee, the seventeen-year-old daughter of William, general storekeeper, and Eliza, née Evans.

Ready’s involvement in politics began in 1903, when he joined the Reform League—a typically ephemeral non-Labor organisation of ostensibly progressive character—but he resigned upon discovering that it was run by those whom he most wished to reform—the big landowners. He became instead an advocate for the cause of Labor, joining the Tasmanian Workers’ Political League and making himself indispensable as a local organiser. In 1908, at a meeting attended by League general secretary James Guy, Ready played a prominent role in the formation of the Campbell Town Workers’ Political League, being rewarded with the position of honorary secretary. The Campbell Town League grew ‘by leaps and bounds’ and soon had a membership of over two hundred. Later that year, Ready helped found the Tasmanian League’s Franklin divisional council, becoming honorary secretary and treasurer. In 1909, he was elected to the executive committee of the Tasmanian League. His growing prominence within the League was not without its costs, however—once his labour sympathies were known, he became a ‘marked man’ in the local district, with some inhabitants boycotting his business. It was thus that Ready first experienced the bitterness that was to beset his political career.

Despite his success as an organiser, Ready appeared reluctant to enter politics. He declined preselection for the state election of 1909, and for a seat in the House of Representatives, before finally accepting a seat on Labor’s Senate ticket for the general election of 1910. Ready won the seat, but again paid a price. As an ardent opponent of the landed interest living in Tasmania’s rural heartland, he was selected for particular attention by his conservative opponents. After a ‘strenuous campaign’, he was ‘confined to his bed by illness’, the first indication, perhaps, that Ready, a capable organiser who referred to himself as ‘a humble student of Democracy’, was less than ready for the harsh world of parliamentary politics.[1]

Ready was an active participant in parliamentary life. He was a member of the select committee on the general elections of 1913, and served on the inquiry into the Mount Balfour (Tasmania) Post Office in 1915. In 1914, he was a member of the royal commission on the fruit industry, which inquired into the production, marketing and distribution of Australian fruit, a matter of vital importance to Tasmania. He was Labor Party Whip in the Senate from September 1914 to March 1917, and assistant secretary of the Caucus. He also continued his service with the Party organisation, being elected a delegate to the interstate conference in 1915 and 1917, and also as a treasurer of the newly established Tasmanian Labor Federation.[2]

In the Senate itself, Ready spoke well on a range of subjects, though he favoured brevity—‘Blessed are those who make short speeches, for they shall be invited again’. Predictably, he supported the proposal to introduce a land tax on large estates. He believed that, as the various state governments refused to tax large estates, it was up to the Federal Government to do so. He also took every opportunity to introduce his state into debate. During discussion of the Electoral Bill in 1911, he spoke out against electoral malpractices in Tasmania. In the debate on the Tasmania Grant Bill, he urged that Tasmania receive the full amount recommended by the royal commission on Tasmanian customs leakage. Yet, Ready was far from parochial. He supported what he saw as progressive measures for the Commonwealth, such as the Kalgoorlie to Port Augusta Railway, and believed that ‘the advent of women into the political arena’ had purified politics. He argued that rural workers should be covered by the Conciliation and Arbitration Act and allied the labour movement with Christianity. He also favoured the Government’s proposal to establish an Australian defence force.[3]

The defining moment of Ready’s political career, however, was the conscription crisis of 1916-17. Speaking on the Military Service Referendum Bill in 1916, he said that he would ‘advise the people to vote “no” at the referendum’, arguing that the Government’s policy would divide the nation and introduce suspicion. Moreover, at the Labor Party’s special conference on conscription in December 1916, he voted for the motion calling for the expulsion of pro-conscriptionists from the Party. While Ready was not prepared to follow Prime Minister Hughes into coalition with the Liberals, he seems nonetheless to have succumbed to Hughes’ designs. On 1 March 1917, Ready resigned suddenly on the grounds of ill health, thereby allowing Hughes to alter the composition of the Senate (in order to extend the life of the Parliament). Ready’s Senate shoes were filled by the speedy appointment to the casual vacancy of the pro-conscription Tasmanian, John Earle.

The ensuing high drama, during which Hughes was accused of ‘juggling with Senators’, reflected badly on Ready, as it did on several other Tasmanian Senators, namely Long, Guy and Earle. Senator Watson saw the incident as a contrivance of government ‘to defeat the people in their determination to prevent the conscription of manhood for compulsory military service abroad’. However, Ready’s political opponent, Senator Keating sprang to his fellow Tasmanian’s defence. Describing how ‘on Tuesday last’, he had come ‘over from Tasmania’ on the same boat as Ready, Keating said that he knew of no member of the Senate who has been more earnest, more diligent or more loyal; indeed, he saw the incident as a personal tragedy for Ready: ‘I … travelled with him so frequently, and came into contact with him … so often, that I shall be the last man in the Senate and in this country to believe that he associated himself with anything wrong or corrupt’. Keating described how he had been lunching in the Parliamentary Dining Room when Ready ‘seemed as if he were done’. Keating then vividly described his colleague’s sudden collapse. He explained that Ready had gone through ‘a period of stress and worry’, and that he was ‘sick of politics’. Senator Gardiner successfully moved for the appointment of a royal commission, but the commission did not meet due to Hughes now being forced to call an election.[4]

Following his resignation, Ready returned immediately to Launceston aboard the Loongana, assisted down the gangplank by his wife. He was quoted as saying that ‘parliamentary life [was] too much for him’, and that he felt keenly the severance of ties with his old political friends and associates, but ‘he had his family and his future to consider’. On 2 March, Ready told the Director-General of Recruiting, who visited him, that he would not continue as chairman of the Tasmanian recruiting committee, though he wished to continue to help in a voluntary capacity. (In fact, Ready had already announced his resignation from this position following the adverse reaction to his appointment in December 1916.) On 9 March 1917, the central executive of the Tasmanian Labor Federation (TLF) requested that Ready explain his actions or face expulsion. Ready, claiming that the resolution appeared in the press before the letter reached him, refused to provide the required statement, and did not reply to a further letter from the TLF. On 1 May 1917, he commented that he had ‘not had a fair deal’, adding that he was glad to be ‘out of the sphere of such Parliamentary pirates who sail under the black flag of malignity and party bitterness’. At a meeting on 15 May 1917, the executive decided that no further action should be taken. Nevertheless, Ready’s involvement with the Labor Party was effectively at an end.

Ready settled down for the next few years at Invermay, Launceston, and operated a small business, the Discount Bicycle and Supply Company. In about 1920, he left Tasmania for Victoria, living in the Melbourne suburb of Kew and working as a publicity agent. He died at Kew on 28 July 1958. He was eighty years of age and described as a dairy broker. His wife and children, Minnie, Thelma, Keith, Hazel and Jessie, survived him. It would seem that following the conscription fracas he lived peacefully with his family for forty-one years.[5]

The conscription debate earned Ready a place in history, though history, like the press of the day, has tended to be less than kind to him. Something of an innocent, he could not withstand the intricacies and intrigue of politics, especially at this time of great national crisis when the strings were being pulled by a master of the political game. In poor health, the stress and strain of trying to forward Tasmania’s belated social reform plan, combined with war and the conscription debate, had been too much for him.[6]

[1] Reg. A. Watson, ‘Controversial End for Launceston Senator: Political Corruption Alleged’, Examiner (Launceston), 17 January 1998, p. 21; Daily Post (Hobart), 22 March 1910, p. 7, 7 April 1910, p. 3, 9 April 1910, p. 3, 18 April 1910, p. 3; Mercury (Hobart), 15 April 1910, p. 6; R. K. Ready, The Truth about the Midlands, Daily Post Print, Hobart, 1910; Senator Ready, What is Socialism? Some Thoughts for Students, reprinted from Daily Post (Hobart), n.d.

[2] CPP, Report of the select committee on the general elections, 1913; Report of the select committee on the post office, Balfour, Tasmania, 1915; Report of the royal commission on the fruit industry, 1914; Patrick Weller (ed.), Caucus Minutes, 1901–1949: Minutes of the Meetings of the Federal Parliamentary Labor Party, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1975, vol. 1, p. 490; Richard Davis, Eighty Years’ Labor: The ALP in Tasmania, 1903–1983, Sassafras Books and University of Tasmania, Hobart, 1983, pp. 119–120.

[3] CPD, 1 July 1910, pp. 16–19, 19 October 1910, pp. 4784–4793, 26 October 1911, pp. 1827–1830, 30 October 1912, pp. 4816–4820, 30 November 1911, pp. 3412–3414,17 November 1910, pp. 6308–6309, 24 September 1913, pp. 1441–1443; CPP, Report of the royal commission on Tasmanian customs leakage, 1911.

[4] ALP, Report of proceedings of the special Commonwealth conference on conscription, Melbourne, December 1916, pp. 4, 12–13, 16; CPD, 22 September 1916, pp. 8828–8831; Marilyn Lake, A Divided Society: Tasmania During World War I, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1975, p. 40; CPD, 1 March 1917, pp. 10779, 10786, 2 March 1917, pp. 10844–10845; Gavin Souter, Acts of Parliament, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1988, p. 152; Mercury (Hobart), 3 March 1917, p. 6; Age (Melbourne), 3 March 1917, p. 10; CPD, 2 March 1917, pp. 10888–10912, 10847, 5 March 1917, pp. 10960–10962, 6 March 1917, pp. 10993–10995, 13 March 1917, pp. 11222–11223, 11268; H of R, V&P, 2 March 1917; Senate, Journals, 13 March 1917.

[5] Age (Melbourne), 2 March 1917, p. 7; Mercury (Hobart), 5 March 1917, p. 3; Daily Post (Hobart), 3 March 1917, p. 5, 13 March 1917, p. 7; Mercury (Hobart), 13 December 1916, p. 4; Daily Post (Hobart), 14 December 1916, p. 4; Examiner (Launceston), 12 March 1917, p. 7; Mercury (Hobart), 2 May 1917, p. 6; Tasmanian Workers’ Political League, Central Executive, Minutes, March–May 1917, NS603/30, AOT.

[6] Lloyd Robson, A History of Tasmania: Volume II, Colony and State from 1856 to the 1980s, OUP, Melbourne, 1991, pp. 329–331; Ernest Scott, Australia During the War, A & R, Sydney, 1943, pp. 379–382; Lake, A Divided Society, pp. 84–85.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 248-251.