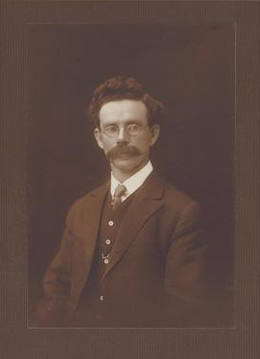

MULLAN, John (1871–1941)

Senator for Queensland, 1913–17 (Labor Party)

John Mullan, ‘a small, pugnacious figure, with a Paderewski-like mop of curly black hair’, impressed his contemporaries as ‘a fluent and somewhat combative debater, with a sprightly Irish wit . . . as nimble and elusive in the dialectical wrestling bouts of the debating floor as the fabled leprechaun of Irish folk-lore’.[1] Mullan was born in Loughlinstown, near Dublin, Ireland, on 8 September 1871, the son of John Ponsonby Mullan, and his wife Mary, née Stanley. He was orphaned as a child and looked after by relatives. After being educated in Dublin National and private schools, he left Ireland in 1888 for Melbourne, where he worked as a clerk. Early in 1890, he moved to Charters Towers, Queensland, where he was employed in the Railway Department until he obtained a permanent job with the Post and Telegraph Department as a letter carrier in 1891. By passing the Queensland Public Service examination, Mullan qualified for higher grades culminating in his control of the money order office and savings bank in Charters Towers for three years.In 1899, he was a founding member of the Charters Towers Literary and Debating Society, where he debated the case against Federation.

Mullan became increasingly involved with the activities of the labour movement. He was an organizer for the Charters Towers Miners’ Union (1905–06) and for the Associated Workers’ Union in Charters Towers (1906–07). He also served as general secretary of the Amalgamated Workers’ Association (1912–13). In 1905, he had resigned from the public service to contest the state seat of Charters Towers as a Labor Party candidate at a by-election. Mullan’s bid to enter the Queensland Parliament failed on this occasion, and again in May 1907, when he sought to wrest the seat of Townsville from one of the two sitting members, a former premier Robert Philp.

It was not until the general election of February 1908 that he was returned as one of the two members for Charters Towers in the Queensland Legislative Assembly. He was re-elected in October 1909, serving as Whip of the Parliamentary Labor Party until defeated in April 1912 following a redistribution of seats and the collapse of the general strike. In his first speech on 13 March 1908, Mullan had advocated dispensing with state governors in favour of lieutenant-governors, and called for the abolition of the non-elected Legislative Council, referring to it as ‘a block on the wheels of progress’. He argued that if the Council could not be entirely removed, the lower House should ‘pluck its fangs . . . and render it practically useless’.[2]

In May 1913, Mullan stood for the Senate, winning a seat in the Labor sweep of that chamber. He was returned again following the double dissolution of 1914. A persistent hard worker, and a spirited and able speaker, his effectiveness in debate rested on a thorough knowledge of his subject. Mullan brought to the Senate the fervour of the trade union leader. ‘Every improvement in the social and industrial laws of this Commonwealth may be traced to the power and influence of the unions of Australia’, he declared. He referred to the Commonwealth’s Conciliation and Arbitration Act, and the improved working conditions brought about by the trade union movement: ‘ . . . we have treated the working classes as men and women . . . thus . . . the whole community has profited’. He declared that ‘political unionism and industrial unionism were married long ago, and the offspring of that alliance [had] been the Labour movement—the grandest movement on earth’. He concluded that ‘unionism without politics is a thing of the dead past’. He castigated the Cook Government’s legislative program as one in which the electoral law was to be attacked, the secrecy of the ballot to be violated and an attempt made to smash unionism and to ostracise bush workers, who would be asked to maintain an army of unemployed.

He advocated the introduction of a national unemployment insurance scheme to be funded by the ‘nation’, rather than by individuals. Mullan opposed the Postal Voting Restoration Bill, criticising it as an attempt to return, by stealth, to methods of open voting which made coercion of voters easier. He rebutted the view that the women of Australia would be disadvantaged were the postal vote not reintroduced and provided statistics on numbers of female voters at elections. He opposed possible reductions to the maternity allowance as an ‘onslaught on the mothers of Australia’. In Question Time, he drew attention to the confusion between ten-shilling and ten-pound notes, urging more distinctive designs and, recalling his post and telegraph experience, he advocated a flow-on of adult wages to grooms and lift attendants in the federal Postmaster-General’s Department.[3]

Mullan was a member of the Federal Executive of the Parliamentary Labor Party from November 1916 to June 1917. He was a passionate ‘anti-conscriptionist’, highly critical of Prime Minister Hughes’ ‘Win the War’ election. During Hughes’ trip to Great Britain in 1916 Mullan strongly advised the Prime Minister to object to British policy on Irish home rule, and suggested that soldiers and armed police in Ireland should be transferred to the front. He criticised those who, given ‘fame and fortune’ by the Labor Party, were now its ‘chief traducers’.

Referring to the Hughes-Cook coalition, he pronounced: ‘ . . . we now have the deplorable spectacle of 29 members of this Parliament, men who were returned upon a definite Labour pledge, sheltering themselves in the trenches of the Liberal party’. Mullan especially objected to Hughes’ attempts to prolong the life of the Parliament until the end of the war without resort to an election, characterising it as ‘immoral and cowardly’. Later, the Brisbane Worker would write: ‘These were stirring times, and Johnny Mullan stood loyally and courageously by Labor in the bitter fights that were then waged to impose conscription on the nation, paying the penalty by suffering defeat in 1917’.[4]

Mullan was a member of the select committee that inquired into the circumstances surrounding the award of a transcontinental railway contract to Mr H. Teesdale Smith. The matter, described by Senator Gardiner as ‘fishy’, led to long and spirited debate, and an amendment to the Address-in-Reply. Mullan objected to the suggestion that he and other members of the committee had prejudged the inquiry. However, as fellow committee member, Senator Oakes pointed out, Mullan’s interjection with reference to the letting of the contract—‘with secrecy and the side door added’—did reflect his attitude to the inquiry. The committee, which reported on 10 June 1914, ceased further inquiry on the basis that the relevant government department had not been forthcoming in meeting the request to examine certain documents.[5]

Following the loss of his seat in the 1917 federal election, Mullan returned to the state scene as an organiser for the Queensland central political executive. He continued as a state convention delegate until 1941; he had been a regular delegate since 1910. He became also a member of the central political executive committee (1920–1941). Finally, in 1936 he was a delegate to the federal ALP conference.

In 1918, Mullan stood for and won the State seat of Flinders. He would hold the seat until 1932 when it was renamed Carpentaria. He continued as a member from 1932 until March 1941. From October 1919, Mullan was a Minister without Portfolio in the Queensland Cabinet. In November 1920, he was appointed Attorney-General, an office he held until Labor lost government in May 1929. Following the conservative Moore Government’s defeat after a three-year term, Mullan again became Attorney-General on 17 June 1932. He relinquished the portfolio because of ill health on 14 November 1940, and did not stand for the 1941 election.

His career in the Queensland Parliament had been a distinguished one. On several occasions, he had acted as premier. He had been identified with significant administrative and legislative reforms, including major changes to legislation relating to juries (1923), workers’ compensation (1926), money lending (1933) and rents (1938). Under his direction, a publication entitled Administrative Actions of the Labour Government in Queensland was compiled. He was responsible for the passage of the Supreme Court Act 1921 and the Hire-purchase Agreement Act 1933.Mullan was known for his genial wit and good humour. His bright and breezy speeches were heard with delight—even by his political opponents. Mullan was recognised as a loyal and stalwart supporter of his party, totally dedicated to its achievements.[6]

After his retirement, he lived at Southport. When ‘Johnny’ Mullan died on 1 October 1941 in the Mater Misericordiae Private Hospital in South Brisbane, he was accorded a State funeral and after a requiem mass at St Stephen’s Roman Catholic Cathedral was buried in Toowong Cemetery. He had married, on 11 September 1895, Mary Farrelly at St Columba’s Church, Charters Towers. Five sons and six daughters resulted from this union. His wife and daughters, Eva, Margaret, Eileen, Josephine, Kathleen and Sheila, and three sons, Bernard, Vincent and Leonard, survived him. One son, Justin, had died of wounds in France during World War I, while another, Ernest, private secretary to his father, had died five years earlier.

Tributes to him as man and politician were generous. Not long before he died, The Worker described him as ‘the sterling democrat, the faithful friend, and the unswerving champion of the rights of the people’. The Australian Law Journal believed that as Queensland’s Attorney-General he had secured ‘the complete confidence of both the public and the legal profession’. One of his oldest political associates and personal friends, William Forgan Smith, referred to him as ‘a very wise counsellor’. To Senator J. S. Collings, Mullan was ‘a remarkable man’, and, in the opinion of Frank Brennan, MP, Mullan ‘upheld the best traditions of the Australian Labour party’ and served the labour movement well.[7]

[1] Clem Lack (comp.), Three Decades of Queensland Political History 1929–1960, Government Printer, Brisbane, 1962, p. 743.

[2] The Charters Towers Literary and Debating Society Minute Book, January 1899 to March 1903, OM 65-8, John Oxley Library, SLQ; D. J. Murphy (ed.), Labor in Politics: The State Labor Parties in Australia 1880–1920, UQP, St Lucia, Qld, 1975, p. 222; QPD, 13 March 1908, pp. 150–5.

[3] CPD, 11 September 1913, pp. 1105–5, 9 December 1913, pp. 3879–83, 22 October 1914, pp. 273-4, 22 February 1917, p. 10560.

[4] CPD, 22 September 1916, p. 8968, 28 September 1916, p. 9043; Senate Journals, 28 September 1916; CPD, 14 March 1917, pp. 11374–5, 11386; Worker (Brisbane), 14 January 1941, pp. 1, 4.

[5] CPD, 6 May 1914, p. 607, 3 June 1914, pp. 1731-1732, 1746; Senate, Journals, 3 June 1914; CPP, Special Report of the Select Committee on Mr Teesdale Smith’s Contract—Kalgoorlie to Port Augusta Railway, 1914.

[6] J. Mullan (comp.), Administrative Actions of the Labour Government in Queensland: During the Period 1915 to 1928, Government Printer, Brisbane, 1929; QPD, 21 September 1921, p. 829, 27 October 1921, p. 1966, 6 September 1933, p. 323, 20 October 1933, p. 899.

[7] Worker (Brisb.), 14 January 1941, pp. 1, 4; Australian Law Journal, vol. 15, 17 October 1941, p. 196; QPD, 2 October 1941, p. 570; CPD, 8 October 1941, pp. 721, 732; Joy Guyatt, ‘Mullan, John’, ADB, vol. 10.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 129-132.