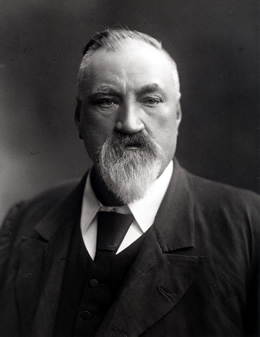

PLAYFORD, Thomas (1837–1915)

Senator for South Australia, 1901–06 (Protectionist)

Thomas Playford, fruit grower and politician of Adelaide, was born at Bethnal Green, London, on 26 November 1837, eldest surviving son of Thomas Playford and his second wife Mary Ann, née Perry. The senior Playford, whose occupation at the time of the birth of young Thomas was that of a clerk at the Horse Guards, migrated with his family to South Australia in 1844 and settled in Adelaide. He later farmed at Mitcham and, as an independent minister, founded a number of Christian churches in the region.

Tom Playford attended school in Mitcham until the age of thirteen, his father having neither the money to meet his son’s desire to attend the new St Peter’s College nor sufficient regard for the legal profession to encourage his ambition to become a lawyer. Instead, Playford worked as an agricultural labourer, educating himself through local literary anddebating societies. On 16 December 1860, he married at St John’s, Adelaide, Mary Jane Kinsman, the daughter of an Anglican clergyman. The couple settled on a small rural property at Norton Summit in the Adelaide Hills, later named ‘Drysdale’. Establishing a profitable orchard of apples, pears, plums, berries and especially cherries, Playford became a founder in 1875 of the East End Market Company, serving as its chairman for all but four years until his death.[1]

Playford’s political career began with his election to the East Torrens District Council. He became chairman after only twelve months, a position he held for twenty-one years (1862–83). In 1868, he was elected Member for Onkaparinga for the House of Assembly, supporting H. B. T. Strangways’ land reform legislation. During his first parliamentary term, Playford was paid ten shillings a day by his father for each day spent on parliamentary duties. In 1871, he moved for the payment of sitting allowances to members of Parliament, but the legislation was lost with the defeat of the government.

Defeated in 1871, Playford was returned for East Torrens in 1875, for Newcastle in 1887, and again for East Torrens in 1890. He served in various ministries as Commissioner of Crown Lands and Immigration or Commissioner of Public Works, then as Premier and Treasurer of South Australia (1887–89, 1890–92), and Treasurer and Minister with responsibility for the Northern Territory in the Government of C. C. Kingston (1893–94). As Premier, he recognised that the first duty of his government was ‘to see that our deficit is extinguished, and that our revenue may be made to meet our expenditure’. As Treasurer, he was responsible for five budget surpluses and a significant reduction of South Australia’s colonial debt. Although he had ‘started life as a free-trader’, Playford’s name became a byword for protection when he introduced South Australia’s first comprehensive protective tariff in 1887. His government was also responsible for legislation restricting Chinese immigration and an act providing for payment of members of Parliament.[2]

Playford played a prominent part in early discussions on Federation. He presided at the meeting of the Federal Council of Australasia in Hobart in 1889, and represented South Australia at the Australasian Federation Conference in Melbourne in 1890. At the National Australasian Convention in Sydney in 1891, Playford was one of seven South Australian delegates, and a member of the Convention’s committee on constitutional machinery, powers, and functions.

Described by Alfred Deakin as a practical premier, Playford thought it crucial to balance the power between the Senate and the House of Representatives by not allowing the former to frustrate government or the latter to override the legitimate interests of the smaller states. Having two Houses with largely coordinate powers, however, required an executive separate from the legislature. He rejected Samuel Walker Griffith’s proposal to allow the Senate the power of veto over money bills, arguing that such power would render responsible government impossible. Playford believed the Senate should have the power to accept or reject money bills—but not amend them—and that ‘each question must be forwarded to the senate separately’. He also preferred that senators should be appointed by the parliaments of the forthcoming states. He considered that direct election would make the Senate a mere ‘reflex’ of the House of Representatives.

Playford was largely satisfied with the Convention’s deliberations. With regard to the Senate he stated: ‘I have come to the honest conviction that if these clauses are carried the senate will have all the powers they ought to have . . .’. He looked upon the forthcoming constitution as a whole ‘as one to which we can fairly ask the people of South Australia to agree’. He said that he would be only too pleased to do all that he possibly could to obtain the agreement of the people of South Australia.[3]

In 1894, Playford was appointed Agent-General in London, where he remained until 1899. Upon his return to South Australia, he was elected to the Assembly for the seat of Gumeracha. He clashed with the Kingston Government over proposals for Legislative Council reform, arguing that to send such legislation to the upper House without first securing the support of its electors was to invite defeat. In November, Playford voted against his former colleagues upon a motion of adjournment, thereby assisting in the fall of the Government. When the new Government fell a week later, Playford was offered the premiership, but declined in favour of F. W. Holder.[4]

One of several Protectionist candidates endorsed by the Australasian National League, Playford was elected as a senator for South Australia on 30 March 1901, and became one of the first six-year senators. In the Senate, Playford supported the White Australia policy, but resented the cost of subsidising the Queensland sugar industry’s transition to white labour. The other colonies, he argued, had borne the cost of keeping Australia white for years—why should they pay Queensland’s share as well? He also believed it unjust to discriminate against people once they were admitted to Australia, stating: ‘We are perfectly at liberty to keep Asiatics out of the country . . . [but] it was not right to pass laws which would injure Asiatics or other people who had once been allowed to become citizens’. He considered it absurd that the naturalised subjects of the various colonies could be denied automatic citizenship of the Commonwealth.[5]

A ‘moderate protectionist’, Playford regarded the introduction of the Commonwealth tariff in 1903 as premature. Nevertheless, he thought it ‘a very reasonable compromise’ between the demands of the Free Traders and the high Protectionists; and asked the Senate, ‘whatever it may do, not to lower the duties which are imposed for revenue purposes, but rather to increase them’. He also supported Imperial preference—though not through lowering tariffs on British goods, but by raising them on goods from other countries.[6]

From the outset, Playford championed economy in government. He thought old-age pensions best left to the states, where officers to administer such schemes were already in place, and regarded the appointment of both the Inter-State Commission and a High Commissioner in London as premature. He warned the Government against being too hasty in consolidating debt—unnecessary expense would be incurred in the rapid conversion of loans. He believed that the building of the ‘transcontinental railway’ could only be justified on the grounds of defence—as a commercial operation it was bound to fail—while the naval subsidy to Britain was a better option than building a fleet. ‘We cannot afford to buy a fleet at the present time,’ Playford stated in 1903, ‘and to go into the London money market for that purpose would, I believe, be a great mistake’. He urged that the site of the federal capital be selected soon, but did not envisage any work occurring for many years. On only two points did he deviate from his guiding principle: he believed a High Court independent of the states was worth the expense, and that the completion of the Adelaide to Port Darwin railway would bridge the continent and bring ‘us into near communication with the east’.[7]

Playford was conscious of the Senate’s ‘unique position, inasmuch as we do not represent population, but the whole of the people’. In supporting the Conciliation and Arbitration Bill in 1904, he urged the Senate to stand upon its rights:

The time may come for us to consider whether the Bill shall be allowed to drop, or a compromise shall be arrived at; but that time has certainly not yet come. No matter how drastic our amendmentsmay be, we ought to make them if we regard them as improvements; and the time will very possibly come when we shall have to consider whether it will be wiser to insist on those amendments, or whether we ought to compromise.

Playford took a dim view of proposals to elect the Senate on the principle of proportional representation. He believed that proportional representation would give minorities a power not their due. However, he supported the Government’s plan for filling long-term casual vacancies that provided for these vacancies to be filled by the next most successful candidate at an election once the periodic vacancies had been settled.[8]

A member of five Senate committees, Playford was an active senator throughout his five years in the new Parliament. He was Vice-President of the Executive Council and Leader of the Government in the Senate in Deakin’s first (Protectionist) Ministry (1903–04), and Minister for Defence (1905–07) and Senate leader in Deakin’s second Ministry. As such, Playford had charge of the Government’s financial legislation in the Senate, a task for which he was well suited. In 1903, he defended the Commonwealth against charges of extravagance made by the states. His tenure as Minister for Defence, however, began inauspiciously, with a frank admission that he was no expert on military matters and that the defences of the Commonwealth were in decline. Yet, he soon mastered the detail of defence administration and, in November 1905, presented a comprehensive account of the state of the forces and advice he had received on how to proceed. His term of office was one of consolidation and policy development, of finding the balance between imperial and national concerns—and the demands of economy—one product of which was the first concrete proposal for the establishment of an Australian navy. Playford himself advocated an army made up largely of citizen soldiers—paid militia, volunteers and cadets—and an Australian fleet whose main role was coastal defence. Australia was, and would remain, under the protection of the Royal Navy.[9]

The only Ministerialist to stand for Senate election in South Australia in December 1906, Playford found himself isolated and was soundly defeated. Deakin, who appears to have regretted the loss of Playford, allowed him to administer the defence portfolio until 24 January 1907, when Playford retired from political life. Thereafter, he divided his time between his properties, ‘Drysdale’ and ‘Helston’. He died at Kent Town on 19 April 1915. His estate was valued at some £23 000 and his wife, five sons and five daughters survived him.

‘Honest Tom’ was a giant, tall and powerfully built, of formidable presence and independence of mind. A plain-speaking, colourful, yet unpretentious man, he thrice refused a knighthood. Regarded as a poor tactician, and prone to political indiscretions, he nevertheless handed on to his grandson, Sir Thomas (Liberal and Country League Premier of South Australia, 1938–65) at least one gem of political wisdom—‘never get into an argument with the newspapers’. On his death, Playford was praised as ‘a sturdy Liberal, with strong, clear views of national interests and a patriotic determination to advance them to the best of his ability’, a man who, though not a brilliant speaker, ‘always held his place in debate’.[10]

[1] John Playford, ‘Playford, Thomas’, ADB, vol. 11; Stewart Cockburn, Playford: Benevolent Despot, Axiom, Kent Town, SA, 1991, pp. 18–21; Advertiser (Adelaide), 20 April 1915, pp. 7, 9; George Sutherland (ed.), Our Inheritance in the Hills, W. K. Thomas & Co., Adelaide, 1889 (Australiana Facsimile Editions no. 204), p. 52.

[2] Gordon D. Combe, Responsible Government in South Australia, Government Printer, Adelaide, 1957, pp. 120, 197; Cockburn, Playford, pp. 21–23; H. T. Burgess (ed.), The Cyclopedia of South Australia, vol. 1, 1907, Cyclopedia Company, Adelaide, pp. 179–180; D. I. Wright, ‘South Australia, Playford and Protection’, South Australiana, vol. 9, September 1970, pp. 63–73; Edwin Hodder, The History of South Australia from its Foundation to the Year of its Jubilee, Sampson Low, Marston & Company, London, 1893, p. 40; SAPD, 8 December 1868, p. 1058, 5 July 1887, pp. 115–116, 120, 18 September 1890, pp. 1254–1266, 20 August 1891, pp. 836–851, 15 August 1893, pp. 894–905; CPD, 29 May 1901, p. 342; SAPD, 18 August 1887, pp. 553–558, 31 May 1888, pp. 4–6, 3 July 1888, pp. 194–206, 16 August 1888, pp. 630–644; SAHA, V&P, 13 September, 14 November 1871.

[3] Alfred Deakin,‘And Be One People’: Alfred Deakin’s Federal Story, with an introduction by Stuart Macintyre, MUP, Carlton South, Vic., 1995, p. 52; H. O. Browning, 1975 Crisis: An Historical View, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1985, p. 58; AFCD, 5 March 1891, pp. 53–60, 17 March 1891, pp. 423–427, 18 March 1891, p. 472, 2 April 1891, p. 594, 6 April 1891, pp. 733–735, 9 April 1891, pp. 921–922.

[4] Cockburn, Playford, p. 23; Combe, Responsible Government in South Australia, pp. 135–136; SAPD, 18 July 1899, pp.132–134, 28 November 1899, p. 918, 29 November 1899, p. 919, 6 December 1899, p. 943, 7 December 1899, p. 944.

[5] CPD, 29 May 1901, pp. 344–345, 3 June 1903, pp. 436–437, 24 June 1903, pp. 1270–1272, 17 November 1905, pp. 5451–5452, 2 July 1903, pp. 1710–1711.

[6] CPD, 29 May 1901, pp. 341–342, 8 May 1902, pp. 12412–12423, 3 June 1903, p. 442, 27 September 1905, p. 2821, 5 October 1906, pp. 6140–6143.

[7] CPD, 29 May 1901, pp. 346–347, 350–351, 3 June 1903, pp. 437–442.

[8] CPD, 29 May 1901, p. 343, 3 June 1903, p. 440, 27 October 1904, pp. 6187–6193, 28 February 1902, pp. 10508–10509, 1 July 1903, pp. 1596–1597.

[9] CPD, 7 October 1903, pp. 5757–5766, 5780, 17 November 1905, pp. 5453–5471, 8 October 1906, pp. 6211–6226.

[10] Advertiser (Adelaide), 13 December 1906, p. 8, 20 April 1915, p. 6; Register (Adelaide), 25 September 1903, p. 4; Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney), 30 September 1903, p. 20; Australian Magazine (Sydney), 1 March 1908, pp. 526–527; Fighting Line (Sydney), 15 May 1915, p.10; Sir Walter Crocker, Sir Thomas Playford: A Portrait, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1983, pp. 8–9; Cockburn, Playford, pp. 23, 229.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 157-161.