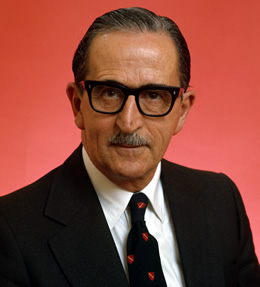

MARRIOTT, John Edward (1913–1994)

Senator for Tasmania, 1953–75 (Liberal Party of Australia)

John Edward Marriott came from a Tasmanian family that maintained strong connections with England. His father, Francis (Frank), was born in London, left school at fourteen, worked in America and then went to sea. Overstaying his ship, Frank settled in Tasmania in 1903, became a farm labourer, and married English-born Alice Maud Harrison. Alice was the daughter of a Church of England clergyman who lived near the Tasmanian town of Elliott, on a small farm which later passed down to the Marriotts. Blinded when an officer in World War I, Frank took his family to England in 1919, where he attended St Dunstan’s School for Blinded Soldiers and Sailors. The family returned to Tasmania the following year, and in 1922 Frank was elected to the Tasmanian House of Assembly for the seat of Darwin, and in 1941 for Bass, which he held until November 1946, when he did not stand for re-election. The seat of Bass was then filled by Frank’s third son, Frederick.

John was born at Elliott, in northern Tasmania on 16 February 1913, the youngest of four brothers. His father was blind, and his mother had suffered deafness from an early age. He would recall his family as close-knit, although impecunious, and with little social life. He was educated at Launceston Church Grammar School and the Hutchins School, Hobart. John was unhappy on the family farm: he ‘hated the mud, the cold and the wet, and the lack of achieving anything’. From 1934 to 1937 he worked in Melbourne in the Australian Broadcasting Commission’s music library. Moved to the sports section, he organised a tour by the ABC Military Band, and had expectations of a career in radio management. Abruptly retrenched, Marriott went to work for J. F. Brady, a land and estate agent in Burnie but was unsuccessful as a salesman. He was then articled to W. J. Manthei, Rose & Co., chartered accountants in Launceston, but did not consider himself either academic or studious.

In January 1939 Marriott joined the 12th/50th Infantry Battalion of the Militia Forces and, in June 1940, enlisted in the AIF and was assigned to 1st Corps of Signals. Commissioned as a lieutenant in July 1942, he served in the Middle East and New Guinea, and on his own telling was ‘happy in the service’. He was demobilised in October 1945 as an honorary captain. On 24 July 1943, at the Anglican Church of the Holy Trinity in Launceston, he had married Myra Viney, a motor transport driver in the Women’s Royal Australian Naval Service.[1]

From 1945 to 1949 Marriott worked as a state organiser for the Tasmanian Liberal Party. No political novice, he had run state election campaigns from 1928 to 1934 for his father and also federal campaigns for two MHRs, George Bell and Charles Falkinder. Politically, John shared his father’s views, whom he called ‘a dyed in the wool Conservative’, and supported free enterprise, King and empire, justice and fair play. By 1946 he had moved from Launceston to Hobart, where he and his wife and their baby lived precariously. He supplemented his income by employment as the Liberal Party’s state publicity officer in 1948, and by part-time secretarial work for Falkinder and for the Tasmanian Leader of the Liberal Opposition, Neil Campbell. In 1950 Marriott took up a full-time post as secretary to the new Opposition Leader, Rex Townley.

Marriot first stood for the Senate at the double dissolution election of 28 April 1951, and almost won a seat. When Tasmanian Liberal senator Jack Chamberlain died in January 1953, Marriott was considered a strong candidate for the ensuing casual vacancy, but he faced opposition from another Liberal candidate, Robert Wardlaw, and from W. G. Wedd, an independent member of the House of Assembly, whom the Labor majority wished to remove from the Tasmanian Parliament. With Labor Premier Robert Cosgrove maintaining the convention that a senator be replaced in a casual vacancy by his party’s nominee, Marriott was appointed by the Tasmanian Parliament on 3 March 1953, with just time to make his first speech before a Senate election in May. In his contest for the seat, he developed an effective style, seizing every opportunity for publicity, and maintaining good relations with the press. He was duly elected. In 1956, when participating in an overseas delegation to the United Nations, Marriott gained credit through a series of detailed reports to the Hobart Mercury.[2]

In the Senate Marriott devoted considerable time to Tasmania as well as to national issues such as repatriation, defence, foreign affairs and health. During 1956 he worked with Labor Senate leader, N. E. McKenna, whom he described as ‘that good Tasmanian and honoured statesman’, to reduce sales tax on goods freighted to Tasmania. Although he believed that the country was living beyond its means, he argued against the introduction of import controls in 1961, fearing their impact on Tasmanian business.[3]

Marriott was re-elected to the Senate in 1958, 1964 and 1970. In the course of his long incumbency the Senate became a more effective house of review with high-powered committees investigating a range of important national issues. Marriott threw his energies into this development, although he criticised Labor’s use of committees to embarrass the Government. On the Joint Select Committee on Parliamentary and Government Publications, he worked closely with Labor’s Lionel Murphy whom he later referred to as ‘a delightful man’. At other times in the Senate, Marriott criticised Murphy’s leadership as ‘inept’. After hearing a mass of evidence, the committee recommended the establishment of the Australian Government Publishing Service, and the development of style guidelines for publications. Marriott became deputy chair of the Select Committee on the Metric System of Weights and Measures, which decided in favour of metrication. As chair of the influential Joint Committee on the Australian Capital Territory from 1968 until 1971, he won respect for his ‘real and lively interest in Canberra’s affairs’. He was deputy chair of a joint committee which, in 1975, recommended the setting up of a register of pecuniary interests, not only for members of Parliament but also for ministerial officers, members of the media and some public servants. Although these recommendations were never fully implemented, the committee’s work presaged the eventual establishment of pecuniary interest registers by the states and the Commonwealth.[4]

Most important was Marriott’s chairmanship of the Select Committee on Drug Trafficking and Drug Abuse, whose report in 1971 advocated a humanitarian approach to the problems of addicts, while urging collaboration among Australian and international agencies to prevent trafficking. Tracing the source of many harmful substances, the report insisted on full control. Even marijuana and cannabis, according to Marriott, might saddle the country ‘with a large population of semi-zombies’. The committee obtained considerable news coverage, making Marriott a well-known figure. In 1970 one journalist, promising confidentiality, published Marriott’s revelation that he himself had had a serious, though now controlled, problem with alcohol. When chairing committees Marriott opposed any hectoring of public servants, holding to the principle that ministers alone are responsible for government policy.[5]

Marriott was a candidate for the post of Liberal Whip in the Senate in 1966, and sought party nomination as a candidate for the presidency of the Senate in 1971. He was unsuccessful on both occasions. In August 1971 he was appointed Assistant Minister, assisting both the Minister for Health and the Leader of the Government in the Senate, holding these posts until the coalition defeat of December 1972. Earlier that year, he had accepted an appointment as an honorary consultant to the United States’ National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse.

During the final year of Whitlam’s Labor Government, Marriott witnessed the developing political crisis with mixed feelings. He was unhappy about Malcolm Fraser’s seizure of the Liberal leadership from Billy Snedden, and the Opposition’s threat to block supply in the Senate. Only after the financial scandals associated with the financier Khemlani did Marriott finally accept the Liberal stance, although when Governor-General Sir John Kerr dismissed Prime Minister Whitlam, Marriott, having suspected that something of the sort was afoot, believed that Whitlam should have been given prior notice of Kerr’s views.[6]

Shortly before the Dismissal, Marriott’s description of the Government’s contribution of $350 000 towards International Women’s Year as ‘a contemptible misuse of public money’, created controversy. A pig’s head was delivered to his Hobart office. To his surprise and that of many political observers, he was summarily dropped from the Tasmanian Liberal Senate ticket after the 1975 double dissolution. Although he responded stoically, contributing $500 to party funds (later returned by one of his supporters) and campaigning for other candidates, Marriott was sorely hurt. He had begun drinking again during 1973 and 1974, until rehabilitated through Alcoholics Anonymous.

In December 1976 he stood for the Tasmanian Legislative Council and was defeated. Marriott was appointed CBE that year, and energetically continued community work. President of the Tasmanian branch of the Australian–American Association from 1971 to 1973 and from 1979 to 1980, and regularly a federal vice-president, he was also president of Hobart Legacy from 1980 to 1981, and an active member of the Anglican Synod. In 1982 he was named Hobart’s Australia Day Citizen of the Year. Marriott died on 13 April 1994 at the Repatriation General Hospital in Hobart, and was privately cremated following a service at the Cathedral Church of St David, Hobart. His wife and daughter survived him.[7]

Interviewed in 1982 for the National Library of Australia, Marriott appeared modest and magnanimous, and a dispassionate judge of his fellow politicians from both parties. A model parliamentary backbencher, Marriott was loyal to his party but possessed an independent spirit and did not fear, on occasion, to cross the floor. In 1954 he was the lone Government dissenter in support of a Labor amendment to the Public Service Act aimed at ensuring the right of appeal for public servants found guilty of minor offences. On 27 November 1957, during the passage of the banking legislation in a closely divided Senate, and with the Liberal Government refusing to grant pairs, the ALP’s seriously ill Senator Arnold was forced to leave his hospital bed in Newcastle to record his vote (which resulted in the defeat of the legislation). Marriott let his disapproval of the Government’s action be known in the circles of his party, and he is still remembered in the Senate for his independence and his integrity.[8]

[1] John Edward Marriott, Transcript of oral history interview with Mark Cranfield, 1982, TRC 917, NLA, pp. 1:1/1–6, 2:1/1–3, 2:1/5–6, 3:1/1–3, 3:1/9–10, 3:2/6–7, 3:2/10–11, 4:1/4, 4:1/7, 4:2/3–4, 5:2/1–2, 5:2/6, 5:2/9; E. J. Smith, ‘Marriott, Francis’, ADB, vol. 15; Mercury (Hob.), 11 Feb. 1957, p. 4; Basil W. Rait, The Story of the Launceston Church Grammar School, School Centenary Committee, Launceston, [1946?], p. 182; The editor acknowledges the assistance of Tony Smithies, The Hutchins School, Hobart; Marriott, John Edward—Defence Service Record, B883, TX3087, NAA; M. Curtis-Otter, W.R.A.N.S., Naval Historical Society of Australia, Garden Island, NSW, 1996, p. 91.

[2] John Edward Marriott, Transcript of oral history interview with Peter Hay, 1988, POHP, TRC 4900/66, NLA, pp. 6:10, 16:8–9; Rosemary Lucadou-Wells, Fifty Year History of the Liberal Party (Tasmanian Division), Liberal Party (Tasmanian division), 1994, pp. 6, 42; Marriott, Transcript of interview with Mark Cranfield, pp. 3:1/2–3, 3:1/6–7, 5:2/9, 6:2/6–8, 6:2/10, 7:1/1–3, 7:1/6, 7:2/1–2, 7:2/10; Mercury (Hob.), 30 Mar. 1951, p. 2, 4 Mar. 1953, p. 1; CPD, 18 Mar. 1953, pp. 1209–12; Mercury (Hob.), 8 May 1953, p. 1, 4 Dec. 1956, p. 6, 12 Dec. 1956, p. 31.

[3] CPD, 13 May 1959, pp. 1390–2, 28 Sept. 1955, pp. 298–300, 9 May 1957, p. 659, 14 May 1957, pp. 694–701, 3 Apr. 1957, pp. 322–5, 12 Oct. 1961, p. 1089, 11 Mar. 1970, p. 236, 9 Mar. 1960, p. 45, 9 Mar. 1961, p. 87.

[4] Marriott, Transcript of interview with Mark Cranfield, pp. 7:1/7, 11:2/4; CPD, 31 Aug. 1967, pp. 421–3; CPP, 32/1964; CPD, 11 Mar. 1970, p. 236; CPP, 19/1968; CT, 15 Oct. 1970, p. 3; Canberra News, 23 Aug. 1971, p. 6; CPP, 182/1975.

[5] CPP, 204/1971; Mercury (Hob.), 18 July 1975, p. 4; Marriott, Transcript of interview with Mark Cranfield, pp. 11:1/7–8, 11:2/8–9, 12:2/1; Herald (Melb.), 7 Oct. 1970, p. 2.

[6] Marriott, Transcript of interview with Peter Hay, pp. 7:11–12; Australian (Syd.), 17 Aug. 1971, p. 3; Mercury (Hob.), 1 Nov. 1972, p. 8; Marriott, Transcript of interview with Mark Cranfield, pp. 9:1/8, 12:2/4; Mercury (Hob.), 20 May 1975, p. 10, 17 Nov. 1975, p. 2.

[7] Mercury (Hob.), 3 Nov. 1975, p. 3, 4 Nov. 1975, p. 7, 6 Nov. 1975, p. 6, 17 Nov. 1975, pp. 1–2, 22 Nov. 1975, p. 2; Marriott, Transcript of interview with Peter Hay, pp. 16:24, 17:2; Marriott, Transcript of interview with Mark Cranfield, pp. 11:1/5–7; Mercury (Hob.), 3 Apr. 1976, p. 3; Australian–American Association, Tasmanian branch, Annual report, 1975–76, pp. 4, 7; Australian–American Journal, vol. 14, no. 5, 1980, pp. 1, 64; Hobart Legacy, Annual report, 1980–81, p. 1; Mercury (Hob.), 14 Apr. 1994, p. 6, 20 Apr. 1994, p. 41.

[8] Marriott, Transcript of interview with Mark Cranfield, pp. 9:2/1–4; CPD, 3 May 1994, pp. 20–7, 28 Oct. 1954, pp. 1109–10, 1119–20.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 3, 1962-1983, University of New South Wales Press Ltd, Sydney, 2010, pp. 143-147.