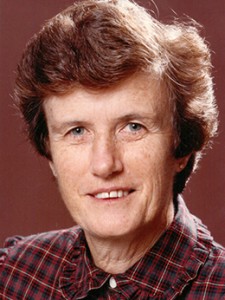

ZAKHAROV, Alice Olive (1929–1995)

Senator for Victoria, 1983–95 (Australian Labor Party)

Throughout her life Olive Zakharov was a grassroots campaigner for human rights and social justice. She eschewed personal publicity and political advancement in favour of promoting the causes and issues that she believed in.

Born in Kew, Melbourne, on 19 March 1929, Alice Olive Hay was the youngest of four daughters of Robert and Alice Anderson Hay, née Dobie. Scottish-born Robert Hay was a teacher and then a journalist, but, with the onset of the Great Depression, he lost his job and spent most of the 1930s out of work, ‘his only income being for piece-rate journalism at tuppence a published line’. For Olive, her first ten years of life were central to the development of her political beliefs; her mother, who was a strong influence, brought her up without ‘guilt or resentment’. However, her mother died young, when Olive was fifteen years old.

Olive attended Ruyton Girls’ School in Kew. After winning a fee-paying scholarship to the University of Melbourne, she commenced an Arts/Social Studies course in 1947, majoring in psychology. She did not complete the course, leaving after only two years. At university, Olive was active in student politics and joined the Communist Party.

On 27 May 1950 in Melbourne, Olive married Graham Stewart Worrall, a fellow member of the Communist Party, whom she had met at university, but they divorced in 1954. From 1949 to 1955 Olive worked variously as a fruit picker, factory hand, pathology assistant, psychiatric nurse, mail sorter, and waitress—experiences which, she said, ‘strengthened my understanding of what it is to be exploited—doubly so if one is female’. While working as a fruit picker Olive met Scottish-born John Zakharov (born Albert Zakharoff), with whom she lived in Beechworth and Yallourn, both in country Victoria. The couple married in Melbourne on 17 April 1954 after Olive’s first marriage was dissolved. They moved to the United Kingdom for a year, returning in mid-1955 shortly before the birth of their first child. They went on to have two daughters and a son. Olive separated from her second husband in the late 1960s and they officially divorced in 1973.

By the early 1960’s Olive Zakharov had left the Communist Party of Australia and joined the ALP. Her ties to the Communist Party from the late 1940s to the early 1960s made her a person of interest to the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO). Later in life she stated her belief that she may have been hampered in her efforts to find work within the public service as a result of her ASIO file. This belief prompted her, in 1992, in her capacity as a member of a joint parliamentary committee on ASIO, to request access to her ASIO file. When her file was provided to her, she noted that most of the material in the file was redacted and, in her opinion, what had been disclosed was either inaccurate or inconsequential. However, to her disgust, her file did reveal that someone had sold her name to ASIO for two shillings and sixpence.

Between 1955 and 1966 Olive Zakharov worked as a market research interviewer and by 1965 had resumed her tertiary studies on a part-time basis at the University of Melbourne. The following year she returned to full-time work as a secondary school teacher at Melbourne’s Montmorency High School while continuing with her studies and raising her children as a single parent. She received an accreditation in teaching from the Melbourne Secondary Teachers’ College in 1967 and eventually graduated as a Bachelor of Arts in 1971. She went on to earn a graduate diploma in educational counselling from the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology in 1975, becoming a registered psychologist and a member of the Australian Psychological Society.

Zakharov taught at Montmorency for seventeen years and, from 1973, was a student counsellor at the same school. She introduced into the school’s curriculum a human relations course which included sex education and appeared in local media promoting the new course, causing controversy in the local community. In 1984, when the Australian Humanist Society declared Zakharov to be the ‘Humanist of the Year’, the citation referred to her ‘pioneering success in introducing humanist counselling into secondary schools’.

Zakharov served on the executive of the ALP’s Montmorency branch for ten years and was a Victorian state conference delegate for thirteen years. In the mid 1970s she was approached by the party to stand for a seat in the Victorian Parliament, but she chose not to put herself forward, preferring to delay seeking public office until after her children were independent. When she did stand for preselection for the Senate for the double dissolution election of 1983, she was placed fifth out of ten ALP candidates on Victorian ticket. In the election, the Bob Hawke-led ALP swept Malcom Fraser’s Coalition Government from office and Zakharov won the tenth and final Senate spot for the state. She was re-elected in 1984, 1987 and again in 1993.[1]

On 25 May 1983 Zakharov began her first speech by noting that she had been elected ‘at a time when the irrationalities of capitalism have inflicted increasing suffering and humiliation on very large numbers of our fellow Australians and most particularly on the weakest’. She spoke of how her previous work experiences had left her with a clear understanding of the significance of real wage cuts for those on low incomes: ‘I know what it is like to be poor and powerless’. She also condemned ‘Long standing and deeply embedded discriminatory practices at all levels of Australian society’, which adversely affected the position of women in the workforce and contributed to ‘their lack of political and economic power’. Zakharov concluded her first speech to the Senate with the declaration that she was ‘a socialist, a unionist and a feminist’, committed to ‘working towards a society where every individual can live with dignity and security’.

Inequality in Australian society remained a central preoccupation for Zakharov throughout her parliamentary career. She was especially concerned with discrimination against women, but she also fought unceasingly for the rights of other disadvantaged groups, such as the disabled, the gay community and Indigenous Australians.

Zakharov stressed the value in providing disabled people with equal employment opportunities, which in her mind could only be achieved by providing them an appropriate level of education and training. When presenting a report of the Standing Committee on Community Affairs on the employment of people with disabilities, she stated:

Australian society must recognise that the community deprives itself of the talents and skills of hundreds of thousands of people as long as it fails to provide a range of appropriate employment options for Australians with disabilities, as well as denying those people the right to fuller participation in the community.[2]

Zakharov was outspoken on all forms of discrimination. At a national conference on violence against Filipino women she condemned the award-winning Australian film The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, saying it portrayed a Filipina as ‘a gold-digger, prostitute, manic depressive and loud, a dehumanised human being’, while the other characters representing minority groups were ‘dignified and made human’. She said Filipino women often settled in Australia as sponsored spouses in outback towns and if subjected to violence, felt they had few or no options.

In her first speech, Zakharov had argued that sexual harassment was ‘one of the worst practices restricting women’s ability to find and keep jobs they want’. When welcoming the Hawke Government’s Sex Discrimination Bill 1983, she indicated it was ‘a very significant step towards Australia becoming a more just and equitable society’. Three years later, when debating the Affirmative Action (Equal Opportunity for Women) Bill, she noted that ‘In spite of the improved position of women, following the passage of the sex discrimination legislation, women are still much overrepresented in the lower paid occupations and underrepresented in higher paid occupations, particularly those which have traditionally been male preserves’. Zakharov argued that affirmative action legislation was the ‘logical extension’ to the sex discrimination legislation as it would help to break down ‘sex stereotyping’ in private sector work environments. She believed that the legislation could help to ensure that women working in the private sector had the same work, training and promotion opportunities as their male colleagues.

While in the Senate Zakharov was able to exert some influence through both party and parliamentary committee work. She chaired a number of Senate committees, including the Standing Committee on National Resources (1985–87), the Standing Committee on Community Affairs (1987–94), the Standing Committee on Employment, Education and Training (1993–94) and the Employment, Education and Training Legislation Committee (1994–95).

Referring to her work on the ALP Caucus status of women committee, Senator Margaret Reynolds described Zakharov as ‘vocal’ in insisting that all portfolios and departments adopt a specific women’s agenda, to help redress what she perceived to be inequality of opportunity between genders. In her committee work, she stood true to her principles, often taking a ‘common sense point of view’. In pursuit of principle, she ‘often took a line that was not always popular with her ministers and/or the bureaucracy’.

In 1985 Zakharov was the lone dissenter on the report of the Select Committee on Video Material which recommended that the federal government should ban the sale of X-rated videos in the Australian Capital Territory, in line with measures taken by other states. She argued that ‘people’s moral attitudes are their own business and as long as material is not demonstrably harmful, and if there is no strong evidence that it could be harmful, it should not be censored’. She followed up these comments three years later, when a joint select committee report was tabled on the classification of commercially available video material, stating that it would be ‘unpardonable arrogance for the state to dictate to its adult citizens what they shall or shall not see, read or hear’.[3]

Although she was a backbencher throughout her time in the Senate, Zakharov, who was a member of the Socialist Left faction of the ALP, was still able to influence government policy. For example, in 1983, during debate on the Family Law Amendment Bill 1983, she drew upon her experience as a former student counsellor to successfully propose an amendment which added schools to the list of places from which a parent could be restrained by injunction from entering. She explained that parents often get caught up in stressful family court hearings and as a result they ‘turn up at schools demanding, sometimes in a very threatening way, to talk to their children’.

Zakharov’s familiarity with the school system would also inform her contributions to Senate debates on school funding. On more than one occasion she spoke about state aid to private schools. She rebutted arguments based on freedom of choice by declaring that ‘Freedom of choice in this sense is not available to most Australians. Fees at the schools where parents are protesting loudest are way beyond the reach of most families’. She also mounted a vigorous defence of the quality of government schools, highlighting that: ‘Every time conservative governments increase the slice of the cake which goes to non-government schools … they are denying the right of a reasonable and good education to students in government schools’.

Zakharov’s idealism inspired many of her Senate contributions. A member and trustee of the Victorian AIDS Council and a member of a subcommittee of the National AIDS Council concerned with education of young people, in April Zakharov told the Senate that effective education about AIDS could not be presented simply as a series of commands or prohibitions; rather, it must be conducted within ‘the context of relationships in general’ and it should teach people ‘how to say no and how to use contraceptives if one has decided not to say no’. The following year, while representing the federal Minister for Health, Dr Blewett, at Australia’s first national sex industry conference in Melbourne, she praised the Australian Prostitutes Collective for its work in educating its workers about the risks of AIDS and the need for them to better protect themselves by engaging in safe sexual practices.[4]

For many years Zakharov was a prominent peace activist. She was involved in protests against the Vietnam War and was a member of the Campaign for International Cooperation and Disarmament. It was said that the only time that Zakharov missed a division in the Senate was when she was outside Parliament House, on the lawns, supporting the women’s peace camp. Her long association with the international peace movement meant that she was the only foreign parliamentarian to be invited to Kazakhstan to witness the destruction of four SS-20 missiles by the USSR on 1 August 1988, eight months after the signing of the Intermediate Range Nuclear Force (INF) Treaty by Soviet Premier Gorbachev and American President Reagan.[5]

Zakharov was also regarded as a ‘committed environmentalist’, with a particular interest in conserving the Antarctic, and Kakadu National Park in the Northern Territory. In June 1989 Zakharov objected vehemently to the Opposition dissent on the recommendations of the Senate Standing Committee on Environment, Recreation and the Arts (of which she was a member) on the potential use and management of the Kakadu park region. She asserted that the dissenting comments simply echoed the views of the mining lobby and were ‘unethical and selective’. She also described the comments, which disclosed in camera evidence given by the Aboriginal custodians of the region, the Jawoyn people, as an ‘abuse of parliamentary procedure’, which resulted in ‘a denial of natural justice’ to the custodians.

Throughout her parliamentary career Zakharov maintained a strong stance against domestic abuse of women. In November 1993 Zakharov revealed publicly that she had been a victim of domestic violence at the hands of her second husband for some years. Her admission coincided with the launch of a national campaign to stop domestic violence against women—by speaking out she had hoped that other victims of abuse would be encouraged to do the same. In a media interview, Zakharov also told of the physical and mental abuse associated with domestic violence, especially given that victims often feel trapped within an abusive relationship: ‘You always think things are going to get better but they don’t … There were no alternatives, no refuges for women, no supporting parents’ benefit and almost no child care’.[6]

Zakharov’s Senate career came to an untimely and tragic end. On 12 February 1995 she had attended the Midsumma gay and lesbian festival in Melbourne to speak out about gay and lesbian rights. When she was leaving the event she was struck by a car on St Kilda Road. She was taken to the Alfred Hospital but never regained consciousness and died in hospital on 6 March 1995, thirteen days short of her 66th birthday.

On the following day sixty-six members of Parliament spoke in tribute to Zakharov and colleagues placed red roses, an international symbol of the socialist movement, on her Senate desk. Gareth Evans, Leader of the Government in the Senate, recalled, in moving the condolence motion in the Senate, ‘Olive’s commitment was not just to issues in the abstract but to the people who were affected by them. She was fantastically supportive of people in distress and of individuals, organisations and community groups needing support and attention.’

A recurring theme of the condolence speeches was Zakharov’s ‘steely determination’ in committing herself to causes that were often unpopular. Senator Rosemary Crowley believed that she possessed ‘in a special way’ a balance ‘between passionate commitment and tolerance’. This was a common sentiment among speakers, who noted that, while Zakharov was fierce and uncompromising in expressing her views, she remained courteous and reasoned in dealing with people. It was said that she placed a good deal of importance in ensuring that those with whom she disagreed understood exactly why she believed what she did.

Her dedication to committee work also drew frequent comment. Members of both Houses referred to the ‘enormous workload’ taken on by Zakharov. As her daughter Jeannie wrote, she ‘was never an armchair activist’. Senator Crowley pronounced: ‘Olive Zakharov was an excellent example of a fine parliamentarian and a splendid example of why women should be in parliament’.

A memorial to Zakharov, unveiled in March 2002, stands in a small reserve, known as Olive’s Corner, in Liardet Street, Port Melbourne. A memorial plaque was also affixed to an existing sculpture in a courtyard on the Senate side of Parliament House, Canberra.[7]

[1] Throughout this entry the author draws on interviews with Olive Zakharov’s sister, Ethyl Temby, and daughter, Jeannie Zakharov. CPD, 25 May 1983, pp. 822–4; Age (Melb.), 8 March 1995, p. 16; ‘Tribute to the late Olive Zakharov’, House Magazine, 22 March 1995, pp. 3–7; ‘Profile: Alice Olive Zakharov’, House Magazine, 7 June 1983, p. 3; ‘Obituary: Senator Olive Zakharov’, Women’s Art Register Bulletin, June 1995, p. 26; M. Reynolds, The Last Bastion: Labor Women Working Towards Equality in the Parliament of Australia, Business & Professional Publishing, Syd., 1995, p. 192; SMH, 15 Oct. 1990, p. 1; Age (Melb.), 26 Aug. 2009, p. 23, 13 April 1992, p. 9, 6 March 1994, p. 8; CT, 3 April 1992, p. 10; CPD, 7 March 1995, pp. 1448–51; CPD, (R), 7 March 1995, pp. 1666–7.

[2] CPD, 25 May 1983, pp. 822–4; Mercury (Hob.), 20 July 1983, p. 20; ‘Opening Addresses, National Council on Intellectual Disability Forum’, Interaction, Vol. 4, No. 4, 1990, pp. 12–16; CPD, 7 May 1992, pp. 2547–8, 2 April 1992, pp. 1580–3.

[3] Mercury (Tas.), 7 Oct. 1994, p. 8; CPD, 21 Oct. 1993, pp. 1934–7, 25 May 1983, pp. 822–4; 22 Aug. 1986, pp. 307–9, 7 March 1995, pp. 1452–3, 1459, CPD (R), 7 March 1995, pp. 1665–6, Select Committee on Video Material, Report, Canberra, March 1985, pp. 73–80; CPD, 28 March 1985,

pp. 948–51, 28 April 1988, pp. 2109–14; CT, 29 March 1985, p. 1.

[4] CPD, 2 April 1987, pp. 1701–4, 7 March 1995, pp. 1448–51, 6 Oct. 1983, pp. 1260–1, 9 Nov. 1983, pp. 2384–7, 8 Dec. 1983, pp. 3540–2, 27 March 1985, pp. 899–901; Australian (Syd.), 26 Oct. 1988, p. 2.

[5] CPD, 7 March 1995, pp. 1448–51, 1452–3; Herald (Melb.), 10 Aug. 1988, p. 3; CPD, 5 June 1989,

pp. 3375–9; CT, 7 June 1989, p. 22.

[6] R Hampton, ‘Senator speaks out about her personal experiences of domestic violence’, transcript, ABC radio ‘PM’, 9 Nov. 1993, CT, 8 March 1995, p. 6.

[7] Age (Melb.), 8 March 1995, p. 16; CPD, 7 March 1995, pp. 1443– 4, 1448, 1458, 1458– 9, CPD (R), 7 March 1995, pp. 1658– 9, 1670, 1670–1, 1675– 6, 1678; ‘Tribute to the late Olive Zakharov’, House Magazine, 22 March 1995, pp. 3–7; Victorian Women’s Trust, ‘Farewell to a Friend, Trust Women’, Newsletter, May 1995, p. 8; Australian (Syd.), 13 March 1995, p. 13; Courier Mail (Bris.), 8 March, 1995, p. 4; Monuments Australia, ‘Olive Zakharov’.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, Vol. 4, 1983-2002, Department of the Senate, Canberra, 2017, pp. 443-447.