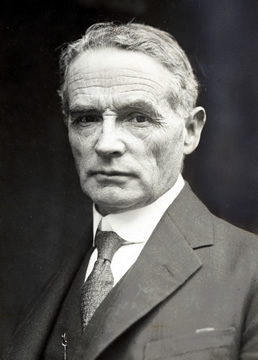

BRENNAN, Thomas Cornelius (1867–1944)

Senator for Victoria, 1931–38 (United Australia Party)

Thomas Cornelius Brennan, the seventh of the eleven children of Michael Brennan and Mary, née Maher, was born in Sedgwick, Victoria, probably in 1867. His father, who was of Irish descent, was a farmer at Maryvale, Upper Emu Creek, near Bendigo; he was three times president, and then secretary, of Strathfieldsaye Shire. Thomas and his younger brother Frank would both enter the law and federal politics—Frank to represent Batman for the Labor Party in the House of Representatives, and Tom (as he was known) to become a senator for Victoria for the United Australia Party. Both would serve as Commonwealth attorney-general, though Tom’s tenure was in an acting capacity.

After attending a local primary school and Bendigo High School, Tom became an apprentice typesetter with the Bendigo Independent (later the Bendigo Advertiser). Moving to Melbourne he worked as a printer with the Argus, where, with others of his family, he would soon be making a mark. In 1907 Freeman’s Journal reported that three of the Brennan brothers were on the Argus staff, and that in Melbourne’s ‘journalistic and legal avenues’ four were in ‘lucrative positions’. Tom progressed to the position of cable sub-editor while continuing his education part-time. He matriculated and in 1892 entered the University of Melbourne to study law, graduating in 1900. On 15 April 1902 he married Florence Margaret Slattery, the daughter of a draper, at St Patrick’s Cathedral, Melbourne. Florence’s occupation on the marriage certificate was given as ‘lady’.

Following his admission to the Victorian Bar in 1907, Brennan left the Argus in favour of legal practice. He received many briefs from his brother Frank’s law firm, but also maintained his connections with journalism. In 1910 he became a founding member of the Australian Journalists’ Association (AJA), on occasion acting on its behalf. Tom would establish a reputation as an outstanding criminal lawyer. He was junior defence counsel in the trial of Colin Campbell Ross, a case on which he based his 1922 book, The Gun Alley Tragedy. He was convinced that Ross was innocent of the crime for which he went to the gallows—the murder of twelve-year-old Alma Tirtschke.

In 1928 Brennan became a King’s Counsel, and throughout the 1930s furthered his standing as a legal authority and commentator on constitutional issues, including those in the arena of criminal law appeals to the High Court. In 1931 he was awarded a doctorate of laws at the University of Melbourne. His thesis, Developing the Constitution: A Politico-legal Essay, was published in 1935 under the title, Interpreting the Constitution.[1]

Brennan was a respected Catholic layman who could publicly argue the Catholic position, as on one occasion in Melbourne when he debated the case for state aid for Roman Catholic schools. He was a founder and first president of the Catholic Federation, served on the committee of the Australian Catholic Truth Society and became the first lay president of Melbourne University’s Newman Society. During World War I his active campaign in favour of conscription brought him into conflict with Melbourne’s Archbishop Mannix. Around this time Brennan was editor of the Catholic Advocate. He endeavoured to maintain editorial impartiality on conscription, but his position was untenable and in April 1917 he resigned.

Brennan stood unsuccessfully as a Liberal for the Victorian Legislative Assembly seats of Melbourne (1911), Warrenheip (1913) and Richmond (1914), and for the National Party in Bendigo East (1921). His political tenacity was rewarded on 12 May 1931 when he was chosen at a joint sitting of both houses of the Victorian Parliament to fill the casual vacancy created by the death of Senator H. E. Elliott. (Before the joint sitting, political wheeling and dealing between the National Party, the newly formed UAP, and the Country Party had led to the Nationalists pressing Brennan to withdraw, which he refused to do.) He took his seat in May and in December was a successful candidate for the Senate at the federal election at which, paradoxically, his brother Frank was defeated.[2]

Brennan brought to bear on the legislative process a sharp legal mind and his knowledge of constitutional law. His political philosophy, informed by the writings of Edmund Burke, was anti‑socialist. He saw it as the duty of government to protect its citizens and considered that the liberty of the individual should be enlarged, rather than restricted, by Acts of Parliament. He strongly believed that the executive should be accountable to the Parliament, speaking against the ‘new despotism’—the executive’s growing tendency to make legislation by regulation.

In keeping with this was his keen support as a backbencher of the Senate’s bipartisan Regulations and Ordinances Committee of which he was second chairman (1932–33). However, his attitude underwent a subtle change after his elevation to the ministry in October 1934. In 1935, during debate on the Dried Fruits Export Control Regulations (not the first of a long list of regulations the committee considered void because of retrospectivity), Brennan opposed the disallowance motion proposed by his replacement on the committee, the UAP’s Senator Duncan-Hughes. The Senate disallowed the regulation, and as the tussle between the Senate and the executive continued, Brennan’s position remained ambivalent, notably during debate on the Acts Interpretation Bill in 1936 and 1937, during which the Government attempted to extend its regulation-making power. As Geoffrey Sawer has written, Brennan was learning of ‘the difficulty of operating a non-party, purely technical control of regulations when their substance was also a matter of political dispute’.[3]

During tariff debates in 1931 and 1933, he was highly critical of trade restrictions, believing that increased import tariffs had not benefited Australia, especially as they had failed to reduce the country’s high unemployment levels during the Depression. He referred to tariff protection igniting secessionist moves by primary producers in Western Australia and suggested that tariff protection should be introduced into Parliament only on the advice of the Tariff Board—a body which, he thought, should be comprised of businessmen and an economist. With the conservative lawyer’s regard for his own profession, he thought that either a judge or a barrister should be chairman of the board.[4]

Above all he was a constitutionalist. In May 1932 the Lyons Government, torn by the Depression, responded to J. T. Lang’s Mortgages Taxation Bill in New South Wales by introducing the Financial Emergency (State Legislation) Bill, which purported to nullify a state statute. Brennan, placing his principles before his politics, had this to say:

The stand I take is that I fear this Parliament has no power to nullify a statute passed by a State if it is within the legislative capacity of the State to enact it . . . At present we are a federation—an indestructible union of indestructible States, and much as I sympathize with the object which the Government has in view, I feel that I cannot be a party to assisting in passing legislation which I strongly believe to be beyond the powers of the Commonwealth.

Labor Senators Daly and Dunn were delighted to support him as they voted against the third reading of the bill, though Brennan himself abstained from voting.

In December Brennan was again tempted to join forces with Daly when a proposed amendment to the Crimes Act placed on persons accused of publishing seditious material the responsibility for proving their own innocence. Brennan clearly agreed with Daly’s denunciation of this as an abandonment of an underlying tenet of British justice—the presumption of innocence until proven guilty—but ‘felt bound to cast on the Government the responsibility for its own action’, and did not vote against the clause. Brennan however did move for the repeal of section 30AB of the Act, an amendment to the Crimes Act made earlier in the year, which provided for what many senators felt were unwarranted powers to the attorney-general. While the amendment passed the Senate, as did the bill on its third reading, the legislation was allowed to lapse in the House of Representatives.[5]

With the formation of the UAP–CP coalition in November 1934, Brennan became Minister Assisting the Minister for Commerce and Minister Assisting the Minister for Industry. While the Attorney-General, R. G. Menzies, was in England from February to September 1935, and February to July 1936, Brennan acted as Attorney-General. He was also Acting Minister for Industry during Page’s sortie to London early in 1936.

Among legislation that he introduced into the Senate as Acting Attorney-General was the Immigration Bill 1935, an amending bill, which responded to the High Court case on Gerald Griffin, a New Zealand communist whom the Government was endeavouring to keep out of Australia, along with Egon Kisch. Griffin had won his case (the judgment referring to the difficulty the High Court faced in responding to a law that was now confused as a result of ‘incongruous draughtsmanship’ in 1901, and ten or more amendments since). Labor Senators Rae and Daly declared the Government’s proposed amendments, which placed the onus of proof on the immigrant charged, a reversal of British justice. Claiming the proposal was merely closing a gap in the White Australia policy, Brennan was unabashed: ‘a man has to establish, by his own evidence, that he is in Australia rightly’. When the bill passed, with House of Representatives amendments requiring the prosecution to prove its case, Senator Rae was ‘thankful for small mercies’.

The Constitution Alteration (Marketing) Bill 1936 sought to rectify the situation brought about by a Privy Council ruling in the case of James v. The Commonwealth by an amendment to section 92 of the Australian Constitution. The proposal failed at the subsequent referendum, but the Privy Council case itself raises an interesting historical footnote on Menzies and Brennan, recounted in A. W. Martin’s biography of Menzies. In 1936, while Brennan was Acting Attorney-General, Menzies had appeared in London before the Privy Council in the James Case, acting on behalf of both the Commonwealth and the State of Victoria, the latter paying him a fee. In the House of Representatives, the fee became a highly charged political issue. While Lyons supported Menzies, others in the UAP were troubled, notably Brennan. He approached Lyons, who in turn raised the matter in a letter to Menzies. On his return Menzies faced a barrage of criticism in the House of Representatives, led by the former Attorney-General, Tom’s brother Frank.[6]

As one of five assistant ministers in the UAP–CP coalition between 1934 and 1937, Brennan piloted through the Senate a number of primary industry bills important to Australia’s economic recovery. He could sustain an argument without unduly hammering the point, as when, during the Flour Tax Assessment Bill of 1934, he put the case for continuing the financing of wheat subsidies with what was known as ‘the bread tax’, and for the gradual diminution of the subsidy itself. He assured wheat growers that the Government would not allow ‘the wheat industry to perish, for with its fall the whole social fabric of the country would be shaken’. There was also that new addition to the menu of the western world, tinned fruit salad, whose status was given definition by the Canned Fruits Export Control Bill 1935 in order to capture growing markets for the delicacy in Britain and America.[7]

Shortly after Menzies’ return from England in 1936, Brennan introduced into the Senate legislation whose purpose was to embody the provisions of the British Official Secrets Act 1920 into Australia’s Crimes Act, pretty much in toto. The provisions of the proposed legislation gave Commonwealth officers powers of seizure so far only exercised in Australia by police, and imprisonment for life for inciting to mutiny. In the latter case, the bill would have removed any requirement to prove intent. In the Senate, Brennan came under fire from both sides. The Opposition was outraged, Senator Collings calling it ‘anti-Australian’. Even the UAP’s Senator Leckie alleged that Brennan had failed to provide a proper explanation of the proposed legislation. The bill was dropped before reaching the House of Representatives. This was not one of Brennan’s finer moments.

Given what seems his increasing ‘toeing of the party line’ it is hardly surprising that there were some heated exchanges between Brennan and Collings, the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate. Collings constantly interjected during Brennan’s measured speeches, and in return Brennan’s responses to the old trade union man from the far north were at times deprecating. The two were about the same age, and differences between them were cultural as much as political. Collings would continue in the Senate until the age of eighty-five, but Brennan was defeated at the federal election of 1937, his term expiring on 30 June 1938.[8]

In August 1935 Brennan’s name had been mentioned as a likely successor to Mr Justice Lukin in the Bankruptcy Court, though in the event Lukin did not retire. With the outbreak of war in September 1939 Brennan offered his services to the Commonwealth Government and became legal adviser to a number of government departments involved closely with the war effort. He died after a short illness, in his home at 1 Otira Street, Caulfield, on 3 January 1944, survived by his wife and two daughters, Claire Ursula and Laura Eleanor. He was accorded a state funeral and, after a Requiem Mass at St Colman’s Church, Balaclava, was buried in the Melbourne General Cemetery. His conscription disagreement with Mannix was long past and at his funeral the final blessing was given by the Archbishop. Brennan was remembered as reserved though determined. One of a small group of commentators who, prior to World War II, had been ‘able to focus on, explain and criticise’ a ‘growing array’ of constitutional cases, he was certainly an intellectual.[9]

[1] Kevin Ryan, ‘Brennan, Francis’ and ‘Brennan, Thomas Cornelius’, ADB, vol. 7; SMH, 4 Jan. 1944, p. 7; Age (Melb.), 4 Jan. 1944, p. 3; Freeman’s Journal (Syd.), 8 Aug. 1907, p. 20; Geoff Sparrow (ed.), Crusade for Journalism: Official History of the Australian Journalists’ Association, Federal Council of the AJA, Melbourne, 1960, pp. 32, 35; T. C. Brennan, The Gun Alley Tragedy: Record of the Trial of Colin Campbell Ross Including a Critical Examination of the Crown Case with a Summary of the New Evidence, 3rd edn, Gordon & Gotch, Melbourne, 1922, p. 2; Argus (Melb.), 8 Aug. 1928, p. 6; Australian Law Journal 15 Dec. 1929, pp. 247–50, 15 Aug. 1930, pp. 106–10, 13 Oct. 1939, pp. 267–9; Argus (Melb.), 26 Aug. 1931, p. 6; T. C. Brennan, Interpreting the Constitution: A Politico-Legal Essay, MUP in association with OUP, Melbourne, 1935.

[2] Niall Brennan, Dr Mannix, Rigby, Adelaide, 1964, p. 79; Catholic Educational Claims: Report of a Public Debate Between The Rev. Joseph Nicholson and T. C. Brennan, Spectator Publishing, Melbourne, 1913; Alan D. Gilbert, ‘The Conscription Referenda, 1916–17: The Impact of the Irish Crisis’, Historical Studies, Oct. 1969, pp. 54–72; VPD, 12 May 1931, p. 68; Bendigo Advertiser, 6 May 1931, p. 5, 12 May 1931, p. 5, 13 May 1931, p. 5; Advocate (Melb.), 14 May 1931, p. 16.

[3] CPD, 28 May 1931, pp. 2354–6, 18 Feb. 1932, pp. 46–51, 22 Oct. 1935, pp. 870–7, 17 Sept. 1936, pp. 208–12, 24 Sept. 1936, pp. 450–63, 3 Dec. 1936, pp. 2813–15, 25 Aug. 1937, pp. 64–78; G. S. Reid and Martyn Forrest, Australia’s Commonwealth Parliament 1901–1988, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1989, pp. 226–8; Geoffrey Sawer, Australian Federal Politics and Law 1929–1949, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1963, p. 91; CPP, Standing Committee on Regulations and Ordinances, third and fourth reports, 1935, 1938.

[4] Argus (Melb.), 7 Oct. 1931, p. 7; CPD, 28 July 1931, pp. 4425–30, 12 Nov. 1931, pp. 1620–8, 6 June 1933, pp. 2104–9.

[5] CPD, 13 May 1932, pp. 729–31, 1 Dec. 1932, pp. 3320–1, 1 & 2 Dec. 1932, pp. 3429–37; Sawer, Australian Federal Politics and Law, pp. 52, 57.

[6] SMH, 9 Apr. 1935, p. 11, 27 Feb. 1935, p. 18; Griffin v. Wilson and Another (1935) 52 CLR 260; CPD, 9 Apr. 1935, pp. 1018–20, 1024–42, 10 Apr. 1935, pp. 1189–90; A. W. Martin, Robert Menzies: A Life, vol. 1, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1993, pp. 186–90.

[7] CPD, 13 Dec. 1934, pp. 1143–4, 18 Mar. 1936, pp. 247–82, 28 Mar. 1935, pp. 418–23.

[8] CPD, 2 Oct. 1935, pp. 381–4, 11 Oct. 1935, p. 687, 31 Oct. 1935, p. 1184, 23 June 1937, pp. 230–5, 8 Dec. 1937, pp. 395–8, 5 May 1938, pp. 887–90.

[9] SMH, 22 Aug. 1935, p. 8; Argus (Melb.), 4 Jan. 1944, p. 3, 5 Jan. 1944, p. 5; Age (Melb.), 4 Jan. 1944, p. 3; Bendigo Advertiser, 4 Jan. 1944, p. 2; Advocate (Melb.), 6 Jan. 1944, p. 12; Tony Blackshield, Michael Coper and George Williams (eds), The Oxford Companion to the High Court of Australia, OUP, South Melbourne, 2001, p. 114.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 2, 1929-1962, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic., 2004, pp. 121-125.