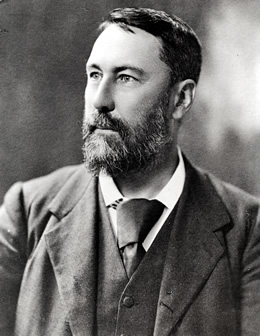

O’CONNOR, Richard Edward (1851–1912)

Senator for New South Wales, 1901–03 (Protectionist)

The first Leader of the Government in the Senate, Richard EdwardO’Connor, was born at Glebe, Sydney on 4 August 1851, the son of Richard O’Connor, librarian of the New South Wales Legislative Council and later Clerk of the Parliaments, and Mary Ann, née Harnett. He attended St Mary’s College, Lyndhurst, and Sydney Grammar School before entering the University of Sydney where, in 1870, he was awarded the Wentworth Medal for the best English essay. A Bachelor of Arts degree was conferred on O’Connor in 1871 and a Master of Arts in 1873.

Employed as a Clerk in the New South Wales Legislative Council (1871–74), O’Connor studied law privately before beginning articles with the future chief justice of New South Wales, Frederick Darley. During the 1870s, O’Connor augmented his meagre earnings by contributing to the Freeman’s Journal, the Echo and the Evening News. He participated in debating societies, notably the Sydney School of Arts Debating Club where he cemented an enduring political friendship with Edmund Barton. Admitted to the Bar on 15 June 1876 (he was to become a QC in 1896), O’Connor established a law practice in Sydney. From 1878 until 1883, he was Crown Prosecutor for the northern district.[1]

Although his political sympathies were protectionist, O’Connor, responding to the ‘strange, irresistible call of Parliamentary life’, was appointed to the New South Wales Legislative Council in 1887 on the recommendation of the Free Trade Premier, Sir Henry Parkes. He was Minister of Justice in the Dibbs Ministry (1891-93) and Solicitor-General from July-December 1893. As Leader of the Government in the Legislative Council from 1892, O’Connor’s sway over the Council, was, according to the Freeman’s Journal, ‘supreme and unquestioned’. He considered no legislative matter beneath his attention. He supported attempts through the Trustees of Schools of Arts Enabling Bill to improve and regularise funding for such institutions. As he piloted the Electoral Reform Bill through the Council, O’Connor, a cautious advocate of electoral reform, reminded his fellow councillors of the limits to their power.

During the lengthy debate on the Commonwealth of Australia Draft Constitution Bill in 1893, he sought to focus discussion on the draft Constitution itself rather than on ‘theories’ more suited to a debating society. In December 1893, O’Connor’s capacity to advance the federal cause in Parliament was diminished. With the Attorney-General, Edmund Barton, O’Connor was forced to resign his portfolio after the Legislative Assembly found that he had acted against the public interest by representing the firm of Proudfoot & Co. in litigation with the New South Wales railway commissioners.[2]

O’Connor remained true to the description of himself and Barton as ‘comrades in the struggle for union’. A member of the general council of the Australasian Federation League of New South Wales from its formation in 1893 until 1900, O’Connor was also a vice-president of the People’s Federal Convention held at Bathurst in November 1896. However, his greatest contribution to Federation was as a New South Wales delegate to the Australasian Federal Convention of 1897-98.

O’Connor served on the Convention’s constitutional committee and, with Barton and Sir John Downer, formed the ‘able, but essentially conservative, trio’ which constituted the Convention’s drafting committee. Determined to preserve ‘the strength and the power of the Senate’, O’Connor was responsible for the inclusion in the draft Bill of the ‘nexus clause’,which became part of section 24 of the Constitution and ensured that the number of members of the House of Representatives ‘shall be, as nearly as practicable, twice the number of the senators’. He argued his case shrewdly, explaining that the provision would ‘automatically [keep] down the expenditure on the parliamentary institutions of the commonwealth’. Joseph Carruthers, a fellow member of the New South Wales delegation, believed that O’Connor and Barton did their best work in 1897–98 ‘by . . . patient listening to others . . . by digesting what was of value in the utterances of others, and by finally reconciling the views of the Convention into a one harmonious whole’.[3] In 1898, O’Connor resigned from the Legislative Council to contest the Legislative Assembly seat of Young as a National Federal candidate, but lost to J. C. Watson, who later became Australia’s first Labor Prime Minister.

In 1901, O’Connor was elected to the Senate. The only Protectionist against five New South Wales Free Traders, he became Vice-President of the Executive Council in the first Commonwealth ministry. The post carried with it the leadership of the Government in the Senate. From the outset, O’Connor was confident that the Senate, ‘co-equal with the representative House’ in all matters except taxation, would find ‘abundant and useful occupation’. On 22 May 1901, he announced ‘the intention of the Government to introduce as many measures as possible, into this House, in order to have . . . a great deal of the useful work of legislation done in this House while Bills are being similarly treated in the House of Representatives’. As Leader of the Government in the Senate, O’Connor played a central role in successfully piloting through the Senate the Commonwealth’s first legislative program. Moving the second reading of the Customs Tariff Bill on 25 April 1902, he said: ‘If there is one principle more than another which I think we should regard in the framing of this . . . legislation . . . it is . . . that no State of Australia, and, as far as possible, that no individual in Australia should suffer unnecessarily by reason of federation’.[4]

On 10 May 1901, O’Connor tabled standing orders, which had been prepared as temporary orders for both Houses by the Clerk of the Parliaments, E. G. Blackmore, in conjunction with the Prime Minister, Edmund Barton. O’Connor described these orders as embodying ‘everything that is reasonable and practical and satisfactory for the conduct of public business’. This did not turn out to be the view shared by the Senate, which requested its own standing orders committee to adapt the draft orders to reflect the Senate’s unique constitutional position. By 1903, O’Connor confessed to having given greater consideration to the standing orders. He went on to comment on the Senate’s financial powers (as framed in section 53 of the Constitution): ‘This question of requests is likely to be the most fruitful battle-ground for contests between the two Houses—the ground upon which we shall exercise our greatest power . . .’.[5]

Although he favoured a White Australia, O’Connor insisted that ‘we cannot take away the right to vote which aboriginals, or those other coloured persons who are naturalized subjects, possess’. He declared: ‘It would be a monstrous thing, an unheard of piece of savagery on our part, to treat the aboriginals, whose land we were occupying, in such a manner as to deprive them absolutely of any right to vote in their own country, simply on the ground of their colour, and because they were aboriginals’. He supported proportional representation for Senate elections, chiefly because it would result in ‘the representation of the true majority’. On 29 July 1903, O’Connor introduced the legislation which created the High Court of Australia with these words: ‘In a House constituted as the Senate is, and so vitally interested in maintaining the balance of the Constitution, it will be hardly necessary for me, I think, to dwell upon the importance of this measure’.

As one of only two Senate ministers—the other was J. G. Drake—O’Connor was torn between the demands made upon him in Melbourne and those of his Sydney law practice. As Vice-President of the Executive Council, he received no salary above that of a senator. In June 1901, he wrote to the Attorney-General, Alfred Deakin, concerning his leadership of the Senate: ‘You know how my heart is in the work & considering all that has happened I would feel disappointed & humiliated if I had to drop out for business reasons before the end of the session’. As a consequence of this plea, and largely at Deakin’s instigation, O’Connor’s fellow ministers each contributed part of their earnings to assist him. In 1902, Barton recommended that O’Connor be appointed KCMG, but O’Connor refused because he feared the possibility of appearing before the bankruptcy courts as ‘Sir Richard’. However, he said he would accept membership of the Privy Council, if offered. In the event, Barton ensured that O’Connor became a judge of the High Court.[6]

O’Connor’s ‘strenuous and eventful years’ in the Senate ended on 27 September 1903 when he resigned to become one of the first three justices of the High Court. O’Connor regarded the judges as ‘not only the interpreters, but the guardians of the Constitution’, maintaining that the Court’s authority on constitutional matters was to be preferred to that of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. In February 1905, he reluctantly accepted the additional post of first president of the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration, but resigned in September 1907. In 1956, Professor Geoffrey Sawer described O’Connor as ‘a man whose ability and independence of mind have always been grossly undervalued by Australian legal tradition’.[7]

While a justice of the High Court, O’Connor continued to garden at his Moss Vale home. As a senator, he had pursued his passion for physical exercise in the parliamentary gymnasium. Indeed, it may have been his enjoyment of trout fishing in the Snowy Mountains which led him to consider Dalgety ‘an ideal site for a Federal Capital’. A member of the Athenaeum and Australian clubs in Sydney, he was also a member of the senate of the University of Sydney and a Fellow of St John’s College.

O’Connor died at St Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney, on 18 November 1912. Following a requiem mass in St Mary’s Cathedral, he was buried in the Roman Catholic section of Rookwood Cemetery. On 30 October 1879, at St Joseph’s Roman Catholic Church, Delegate, he had married Sarah Jane, daughter of J. S. Hensleigh, of Bendock, Victoria. O’Connor’s wife, two daughters, Winifred and Kathleen, and four sons, Arthur, Desmond, Richard and Roderic,survived him. A fifth son predeceased him. Richard and Roderic were to die on active service at Armentières in 1916.

The tributes to O’Connor were heartfelt and generous. Alfred Deakin, describing him as ‘the most lovable of comrades’, remarked on ‘the steadfastness with which he [O’Connor] at all times pursued high Federal aims . . . and how invaluable his counsel and assistance were in dealing with the many great difficulties surrounding the launching of the Constitution’. William Morris Hughes reflected that O’Connor ‘never exhibited any trace of personal enmity’. Recalling a friendship of fifty years, Barton spoke of O’Connor’s ‘unwearied care and consummate ability’ as he conducted ‘the early laws’ of the Commonwealth through the Senate.[8]

[1] Henry Manning, ‘Richard Edward O’Connor’, Australian Law Journal, vol. 25, no. 3, 19 July 1951, pp. 116-118; Martha Rutledge, ‘O’Connor, Richard Edward’, ADB, vol. 11; Freeman’s Journal (Sydney), 5 September 1903, p. 15; Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney), 24 March 1888, p. 584.

[2] Manning, ‘Richard Edward O’Connor’, Australian Law Journal; Freeman’s Journal (Sydney), 5 September 1903, p. 15; NSWPD, 29 November 1893, p. 1443, 16 December 1891, p. 3715, 22 November 1893, p. 1236, 7–8 December 1893, pp. 1727–1728, 1771-1772.

[3] ‘The Late Mr Justice O’Connor’, (1912–13) 15 CLR; L. F. Crisp, Federation Fathers, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1990, p. 322; AFCD, 15 April 1897, p. 684; AFCD, 3 March 1898, pp. 1828–1838, 13 September 1897, pp. 432–433; Sir Joseph Carruthers, ‘Autobiography’, MS 5136, p. 21, NLA.

[4] CPD, 22 May 1901, p 118, 25 April 1902, p. 12003.

[5] E. G. Blackmore, Standing Orders Relative to Public Business, 10 May 1901 (Department of the Senate), rev., 23 May 1901; CPD, 10 May 1901, p. 31, 21 May 1901, p. 36, 23 May 1901, p. 275, 5 June 1901, pp. 653, 687, 12 August 1903, p. 3438.

[6] CPD, 13 November 1901, p. 7141, 9 April 1902, pp. 11453, 10 April 1902, p. 11584, 31 January 1902, p. 9542, 29 July 1903, pp. 2693–2706; R. E. O’Connor to Alfred Deakin, 21 June 1901, Deakin Papers, MS 1540, NLA; Information provided by Geoffrey Bolton from Chamberlain Papers, MSS 14/1/1/45, University of Birmingham.

[7] CPD, 30 September 1903, p. 5525; Deakin v. Webb, Lyne v. Webb (1903–04) 1 CLR 585 at 631; The Times, 20 November 1912, p. 7; Geoffrey Sawer, Australian Federal Politics and Law 1901–1929, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1956, p. 331.

[8] R. E. O’Connor to Alfred Deakin, 21 February 1905, Deakin Papers, MS 1540, NLA; SMH, 19 November 1912, p. 9; Daily Telegraph (Sydney), 19 November 1912, p. 9; CPD, 19 November 1912, pp. 5593–5594, 20 November 1912, pp. 5644-5646; ‘The Late Mr Justice O’Connor’, (1912–13) 15 CLR.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 27-30.