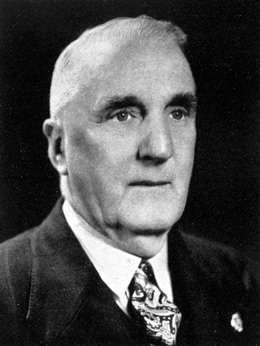

CHAMBERLAIN, John Hartley (1884–1953)

Senator for Tasmania, 1951–53 (Liberal Party of Australia)

In October 1917 Chamberlain enlisted in the AIF, joining the 12th Battalion in France in August 1918. He was wounded on active service and returned to Australia in May 1919. After discharge, Chamberlain became a soldier settler, farming at Preston, west from Latrobe. One of the few such men to enjoy success, even he, as the Senate later heard, knew hard times during the Depression. Meanwhile Chamberlain became a foundation member of the Returned Sailors’ and Soldiers’ Imperial League of Australia sub-branch at Ulverstone, and branch president from 1925 to 1927. In June 1929 he was part of a vibrant and successful annual conference at Scottsdale. According to the Examiner’s report, headed ‘Soldiers’ Parliament’, there were many splendid debates, ‘lit by flashes of wit’. The agenda included Anzac Day, repatriation regulations, preference to returned soldiers and war service homes. The following year Chamberlain was elected to the league’s state executive on which he served until 1947. High among his other civic interests was the Agricultural Bureau movement, which strove to improve farm practice and rural amenity, and of which he was president for some years. Chamberlain seemed to combine jovial good will with decent integrity.[2]

In June 1934 Chamberlain moved into politics and as a Nationalist (that term continuing to be used by non-Labor within Tasmania) won a House of Assembly seat in the Darwin (subsequently Braddon) electorate. This was despite the general election inaugurating a long period of ALP government dominated by A. G. Ogilvie (to 1939) and Robert Cosgrove (1939–47, 1948–58). In the years ahead Chamberlain proved true to his background, ever upholding local and rural interests. In 1935 he carried an amendment against the Government so as to exclude country areas from a clause of the 1935 Totalisator Bill, which would have barred anyone employed by a racing club from being a member of that club. Chamberlain also fought legislation that exempted schools from the payment of council rates, condemning this intrusion on municipal discretion. The coming of another war encouraged Chamberlain to take a somewhat broader stance. He deplored the failure of the federal authorities to decently equip early volunteers for the second AIF, and was active in prompting Parliament to call upon Eire to join the Allied cause. The welfare of a new generation of ex-servicemen inevitably came within his sympathies, while he looked askance at talk of the settlement in Tasmania of Jewish immigrants, or the employment of Italian prisoners of war.[3]

Chamberlain’s central concerns remained such matters as the Tasmanian potato industry, shipping services to the Bass Strait islands, and the provision of electricity to country areas. He also took a perennial interest in the maintenance and upgrading of road and rail services in the north‑west of the state, and introduced legislation to authorise improvements to the water supply of various towns. Always sensitive to chicanery (back in 1934 he criticised the United Australia Party for restoring federal politicians’ salaries), on a number of occasions he probed for evidence of ALP corruption.

Chamberlain worked more through questions than debate, and, as his career progressed, he became increasingly involved in the work of parliamentary committees. From 1942 he sat on the Joint Standing Committee on Public Works, becoming vice-chairman (1942) then chairman (1948). He served too on the Public Accounts Committee (1946–49) and various ‘House’ committees. Nonetheless, and recognising that the Tasmanian Liberals claimed modest talents, it surprises that Chamberlain should have been elected Deputy Leader of the Opposition in November 1949. His parliamentary performance became no more dynamic, and in June 1950 the office changed hands, Chamberlain not standing for re-election and a younger man getting the job.[4]

Perhaps it was this episode that caused Chamberlain to resign from the Assembly and fight the Senate election in April 1951, with Liberal Party endorsement. It was stated that ‘because of his service in the State Parliament, and his widespread popularity, he would considerably strengthen the Liberal team’, a view that was justified by his strong performance at the election, when he polled particularly well in the state’s north‑west. His first Senate speech came with the Address-in-Reply debate in June. He stressed on one hand the contribution of farmers (especially Tasmanian ones) in the face of many difficulties, and on the other the threat of international communism. Subsequently, Chamberlain spoke often on repatriation, arguing for the consolidation of pertinent legislation, and on defence. He showed more general awareness in urging the Government to follow Canada in ceasing to means-test welfare payments, and in promoting nationwide emulation of South Australia’s achievements in providing housing for war widows. Chamberlain regularly brought to the Government’s attention the problem of Tasmania’s geographic isolation and the island’s need for adequate shipping services. He raised concerns about the cost and availability of such farm necessities as superphosphate and agricultural machinery, and about the future viability of the farm sector as a whole. One of his last parliamentary questions sought assurance as to airport services at Devonport and Wynyard.[5]

His home ever had remained in that region, and there, at Ulverstone General Hospital, Senator Chamberlain died on 16 January 1953, three years before his term was due to end. His wife, son Phillip, and daughters Winsome (Mrs A. Chisholm) and Nancy (Mrs L. Billing) survived him. His funeral, which was attended by over one thousand people, including representatives of the Commonwealth and Tasmanian Parliaments, the Liberal Party and the Returned Sailors’, Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Imperial League of Australia, was held at the local Presbyterian church, where he was described as ‘a regular attendant at the church and a communicant’. Among the several obituarists who extolled Chamberlain’s virtues perhaps most germane was Labor’s Senate leader, N. E. McKenna, who found in Chamberlain’s career a ‘golden thread of loyalty . . . to his family, to his constituents, to his party and to the various bodies with which he was associated’.[6]

[1] Examiner (Launc.), 9 Apr. 1890, p. 3; Laurence F. Rowston, One Hundred Years of Witness: A History of the Hobart Baptist Church, 1884–1984, Hobart Baptist Church, Hobart, 1984, p. 17.

[2] Chamberlain, J. H.―War Service Record, B2455, NAA; CPD, 14 Oct. 1952, p. 2986, 20 June 1951, p. 113; Mercury (Hob.), 17 Jan. 1953, pp. 1-2; Examiner (Launc.), 6 June 1927, p. 5, 7, 2 July 1928, pp. 5, 6, 3 Aug. 1928, p. 7, 3 June 1929, p. 11; The editor is indebted to Mr Harold Priestley and to Mrs R. O’Connor, RSLA, Tasmanian Branch, for information; Advocate (Burnie), 17 Jan. 1953, p. 21.

[3] Mercury (Hob.), 8 Aug. 1935, p. 13, 28 Nov. 1935, p. 2, 27 Oct. 1937, p. 10, 14 Dec. 1939, p. 3, 13 Dec. 1940, p. 2, 22 May 1941, p. 5; Lloyd Robson, A History of Tasmania, vol. 2, OUP, Melbourne, 1991, p. 502.

[4] TPP, 1934-1951; Mercury (Hob.), 22 May 1941, p. 5, 8 Aug. 1935, p. 13, 26 Oct. 1934, p. 4, 15 Nov. 1939, p. 2, 19 Nov. 1943, p. 6, 27 Feb. 1948, p. 4, 10 Nov. 1949, p. 1, 7 June 1950, p. 1, 28 Sept. 1946 (magazine), p. 2; Examiner (Launc.), 7 June 1950, p. 3.

[5] Mercury (Hob.), 21 Mar. 1951, p. 2; CPD, 20 June 1951, pp. 112-13, 18 Sep. 1952, p. 1631, 20 June 1951, p. 74, 5 Mar. 1952, p. 781, 8 Oct. 1952, p. 2615, 20 June 1951, p. 113, 9 Oct. 1952, pp. 2751–2, 27 Sept. 1951, pp. 124–5, 31 Oct. 1951, p. 1315, 5 Nov. 1952, p. 4155.

[6] Advocate (Burnie), 17 Jan. 1953, p. 21; Mercury (Hob.), 19 Jan. 1953, p. 2; CPD, 18 Feb. 1953, pp. 12-14.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 2, 1929-1962, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic., 2004, pp. 228-230.