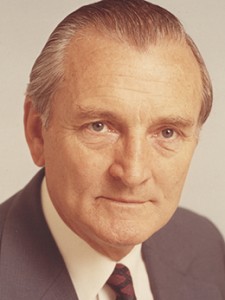

CARRICK, Sir John Leslie (1918–2018)

Senator for New South Wales, 1971–87 (Liberal Party of Australia)

John Leslie Carrick was born in Sydney on 4 September 1918, the fourth of six children of Arthur James Carrick, a clerk, and his wife, Emily Ellen Jane, née Terry. During the Depression years Arthur lost his job in the Government Printing Office. In hindsight John Carrick believed that straitened circumstances made the family more close-knit. Evicted from ‘a large rambling house’ at Woollahra, they embarked on a succession of moves that took them to Randwick and eventually to Bondi.

John attended government schools at Woollahra and Randwick before gaining admission to the selective Sydney Technical High School. Thereafter he enrolled in night classes in pure chemistry at Sydney Technical College. By day he delivered accounts for the Australian Gas Light Company (AGL), and later worked in the company’s industrial department. Awarded an AGL cadetship, he studied economics at the University of Sydney, debated at the University Union, and joined the Sydney University Regiment, through which he was commissioned in 1939. Carrick graduated with a Bachelor of Economics in 1941.

In December 1940 Carrick enlisted in the AIF. Posted to the 18th Anti-Tank Battery, his unit was deployed to West Timor as part of Sparrow Force in December 1941, with orders ‘to deny the island to the enemy’. Two months later, the under-manned defenders were over-run by Japanese paratroopers. Lieutenant Carrick, together with other survivors, was shipped to Java in July 1942 and in September to Singapore’s Changi camp, before being dispatched in early 1943 to the Thailand-Burma railway and its infamous Hellfire Pass. Carrick acquired sufficient Malay and Japanese to act as an interpreter and afterwards described his captivity as ‘a great and enduring learning experience’, which, through ‘the strong amalgam of mateship’, disclosed reserves of spirituality and moral strength in his fellow prisoners. He came to believe that ‘it is the systems … not people that cause the monstrous tragedies’. He therefore declined to testify against individual Japanese ‘puppets’ charged with war crimes because ‘although I had seen many atrocities, I saw the evil compulsion of the system on the individual’.[1]

After Carrick had returned to Australia in October 1945 he enrolled in a law course at the University of Sydney. In his ‘heart of hearts’ he wanted to study medicine, but was frustrated to find that he was ineligible for a Commonwealth Reconstruction Training Scheme scholarship. He took a job as a research officer for the New South Wales Division of the Liberal Party in January 1946. Nearly two years later, still not knowing what he wanted to do, senior party members persuaded him to become the general secretary of the NSW division, a position he held until his election to the Senate in 1971.

In 1948 the fledgling Liberal Party was scarcely three years old. The party’s dilapidated offices in Sydney’s Ash Street opened directly onto the street, which was not disadvantageous in promoting the image of an accessible, community-based party, alive to the needs of ‘struggling families’. But fiscal stringency was real enough—’we lived in musty penury over the whole of my time’, Carrick recalled—and limited his efforts to build a professional organisation. Despite this, he managed to run ‘a very successful enterprise on an absolute shoestring’. His ideas about party systems, and the meaning of liberalism, were published in 1949 as The Liberal Way of Progress.

Carrick developed ‘continuous campaigning’—’You can’t fatten the pig on market day’—and expended about half his budget on field officers, deployed in state and federal electorates across New South Wales. Together with William (Bill) Spooner, who was president of the NSW Liberal Party until 1949 and a dominant force in NSW Liberal politics, he spent much time ‘wandering round this State … looking for candidates everywhere round the place’. He helped form party branches, including encouraging Alister McMullin ‘to form the Scone branch’, and identified locally prominent individuals for preselection. Some forty years later, Carrick frankly stated that his and Spooner’s ability ‘to flush out first class candidates’ was an important reason ‘for the huge and continuing success’ of the Menzies Government.

Carrick believed that party organisers could exert ‘a profound effect on politics in the nation’ through ‘participating in the flow of policies, and shaping tactics and strategies’. The Bulletin dubbed him ‘the grey eminence of Ash Street’ and captioned his photograph, ‘Smiler with a knife’. Sensitive to unravelling socio-economic and sectarian allegiances, Carrick devised a strategy to hasten the detachment of upwardly mobile Catholics from the ALP by providing limited state aid for independent schools. Carrick’s pragmatism was complemented by Prime Minister Menzies’ belief that direct assistance to independent schools, announced in the run-up to the 1963 federal election, was justified in the interests of ‘fairness’. This was an issue, Ian Hancock has written, ‘where moral principle and political advantage were happily aligned’.[2]

Throughout the 1960s there were persistent rumours of Carrick’s impending resignation. He was wretchedly paid; with three daughters at school, his wife, Diana Margaret (Angela), née Hunter, whom he had married on 2 June 1951, worked ‘to keep us going’; and the family lacked long-term financial security. He later recalled that he received some lucrative business offers and thought of pursuing an academic career, but amid the political instability following the death of Harold Holt, he wanted to avoid the impression that he was ‘getting off a sinking boat’. Spooner first mooted Carrick’s succession before his retirement from the Senate in 1965, but it was not until McMullin announced his intention to retire that Carrick was persuaded to seek preselection for the 1970 half-Senate election. Placed second on the NSW Liberal ticket, Carrick was elected on 20 November 1970, his term beginning on 1 July 1971. Re-elected in 1976, he headed the ticket in 1980 and at the double dissolution election of 1983.

Sworn in the Senate on 17 August 1971, Carrick was apprehensive ‘about my own abilities to dance in the sun. I’d spent most of my life largely out of the thrust and parry of the day’. His first speech, during the budget debate on 8 September 1971, foreshadowed his future role as an architect and advocate of the Fraser Government’s ‘New Federalism’ policy. Proclaiming himself a ‘confirmed federalist’, he proposed a redistribution of taxation powers to the states, new ways of raising revenue and a conference of the Commonwealth and the states ‘to undertake a major demarcation of function’, particularly in health and education.

On the following day Carrick made an impressive speech in support of a private senator’s bill, introduced by the ALP’s Lionel Murphy, to abolish the death penalty in federal jurisdictions. A ‘complete opponent of capital punishment’, which he defined as ‘legal murder’, Carrick based his argument on the principle that ‘upholding the sanctity of life’ was fundamental in a free society and that this principle went beyond the issue of capital punishment to embrace the whole ‘spectrum of human life—indeed from foetal life to natural death’. Carrick was one of three government senators who chose to exercise a conscience vote in support of abolition, and the bill was passed by the Senate, but defeated in the House of Representatives. A similar measure was enacted under a Labor Government in 1973.[3]

Carrick championed the Senate as ‘the only safeguard against unbridled power and arrogance’. He was a ‘fervent believer in the powers of the Senate’, regarding it as ‘one of the most powerful Upper Houses in the world’, and relished the ‘great opportunities’ which its membership—only half the size of the House of Representatives—presented for senators to participate in debate. Critical to the Senate’s ‘growing importance’ were its committees, each of them, he said, ‘virtually a little Senate in itself’. Rather than being short of opportunities to analyse issues keenly and make their views known, senators were ‘overwhelmed with opportunity’. So much so that Carrick was fearful lest committees in general ceased to be ‘effective instruments’ and became ‘dominating masters’, with the focus on their work overshadowing the Senate’s essential role as a states’ house. Committees, he thought, should ‘be like Vegemite—a little use makes a very piquant taste … but overdone the whole meal is completely ruined’.

Carrick’s thoroughly prepared speeches were delivered in brisk, soldierly tones, and he was a highly effective orator, but his courtly politeness gave place in the Senate chamber to provocative needling of senators from the other side. His speeches, in consequence, were seldom heard in silence. His closest friend was Senator Robert Cotton, but most parliamentary colleagues and members of the press gallery found him intensely private. According to Labor Senator John Button, Carrick ‘gave little away’ and ‘was singularly successful in getting under the Opposition’s skin’. A gift for hyperbole and a retentive memory, stocked with apt quotations, supplied ammunition for witty rejoinders.[4]

When Gough Whitlam’s Labor Government took office in December 1972, Carrick ramped up his rhetoric, condemning Labor’s ‘brawling, Rabelaisian, Bacchanalian kind of state … in which the individual is lost in the mob’. The government was without a majority in the Senate, and from the commencement of the Parliament, the Senate subjected government measures to vigorous scrutiny. In the privacy of the party room, Carrick and several other Coalition senators urged caution when their leaders announced they would defer the government’s appropriation bills until Prime Minister Whitlam agreed to seek a House of Representatives election at the same time as the Senate election, due in May 1974. Despite controversy over the government’s thwarted attempt to secure a Senate majority by appointing Democratic Labor Party senator Vince Gair as Ambassador to Ireland, Carrick thought there were insufficient grounds for an early election: ‘It looked like opportunism, as I think it was, a belief by [Labor] that it had the divine right to govern and it could take a quick trick, and I’d been in too many election campaigns to think that quick tricks pay off’. On 10 April 1974 Murphy treated the Opposition’s ‘slick motion’, an amendment to defer an appropriation bill in the Senate, as a denial of Supply. Whitlam thereupon called on the Governor-General and secured a double dissolution under section 57 of the Constitution, citing six bills that had been twice rejected by the Senate. The Whitlam Government was returned to office with a reduced majority and again without control of the Senate. With hindsight, Carrick concluded that the Coalition had committed a ‘major error’ by provoking a double dissolution election in 1974 instead of waiting for a general election in 1975.

After the 1974 poll Liberal leader Billy Snedden included Carrick in the shadow ministry, giving him responsibility for urban improvement, albeit with some reluctance, as he doubted Carrick’s loyalty. In fact, Carrick appears to have played a central part in gathering support among NSW Liberal MPs for the replacement of Snedden by Malcolm Fraser in March 1975. Fraser gave Carrick the shadow portfolio of federalism and inter-government relations.

Burgeoning budget deficits, estimated by the Coalition to total $5365 million for the years 1974–76, prompted Carrick and Cotton to use debate on the 1975 Loan Bill to probe how the government proposed to fund these deficits, and the nature of any borrowings. Their pursuit of additional information delayed the bill until the government was under further attack over revelations of attempts by the Minister for Minerals and Energy, Rex Connor, to raise overseas loans by unorthodox and, eventually, unauthorised methods. On 15 October 1975 the shadow ministry resolved unanimously to defer the Loan Bill and two appropriation measures, and acted accordingly in the Senate during the next three weeks. Carrick forcefully defended the Opposition’s actions, citing the ‘corruption, dishonesty and disastrous inefficiency’ of Labor ministers, and subsequently said that he took ‘full responsibility’ with other Opposition senators for precipitating the crisis that led to the Governor-General’s dismissal of the Whitlam Government on 11 November 1975. As far as Carrick was concerned, the deferral of appropriation measures was ‘the traditional constitutional practice in order to bring about an election’. In Malcolm Fraser’s caretaker government, Carrick held the portfolios of Housing and Construction, and Urban and Regional Development. Fraser elevated him to Cabinet, as Minister for Education and Minister Assisting the Prime Minister in Federal Affairs, after the Coalition parties won government and a Senate majority in the double dissolution election of 13 December 1975.[5]

Carrick cared passionately about education. His first experience of Senate committees was as a member of the Senate’s Standing Committee on Education, Science and the Arts; he said: ‘Few matters in my period of public life have given me such very real interest, satisfaction and indeed challenge’ as participation in that committee’s inquiry into the Commonwealth’s role in teacher education between 1971 and 1972. While he believed that ‘the real role of education is to stimulate people in mind and spirit for what is a limitless adventure’, he also believed that education ‘must be adequate for vocation’. Carrick established the Tertiary Education Commission (1977–87, from 1981 the Commonwealth Tertiary Education Commission) to oversee the co-ordination of national tertiary institutions, and he assisted the states by providing federal funding for TAFE colleges to implement the Education Program for Unemployed Youth (EPUY), subsequently commissioning the Australian Council for Educational Research to undertake a year-long study of the program’s effectiveness. During his tenure as education minister, a committee of inquiry, known as the Williams Committee, undertook a major study of post-secondary education with particular attention to market needs. Carrick recalled that, in Cabinet, he: ‘fought like a Kilkenny cat … against the principle that any committee of Cabinet’ could tell him where the education budget should be cut.[6]

On 7 August 1978 Fraser appointed Carrick Leader of the Government in the Senate. He succeeded Senator Reg Withers who was sacked by the prime minister after a Royal Commission found he had committed an ‘impropriety’ by communicating with the chief electoral officer about a proposed redistribution in Queensland. Fraser ignored protests from sixteen Coalition senators and deflected suggestions (repeated after the 1980 election) that the leader in the Senate should be elected rather than appointed. Withers, shrewd and accessible, had been adept at dealing with unhappy back benchers; Carrick adopted a more hierarchical management style which derived from his wartime experience. When the Senate was sitting he lunched once a week with his front bench (whom, he said, gave him ‘absolute loyalty’), met with the Whips twice a day, and left them to carry messages up and down the line. From July 1981, five Australian Democrats senators shared the balance of power with Independent Senator Brian Harradine (Tas.), but Carrick declined to make any ‘behind the chair’ arrangements with minority parties or independents. He later acknowledged that some believed that he had run the Senate in ‘much too rigid a way’.[7]

In the chamber, as the representative of the prime minister, Carrick answered a majority of questions on most days. Canberra Times journalist Andrew Fraser recalled that he:

… maintained a rigid appearance and procedure, often leaning toward his interlocutor and taking a note as each question was unfolded to him. His answers, rarely long and always measured, concluded with him quietly crumpling the small piece of paper … and putting it in the bin, an action seemingly conveying [his] belief that the matter had been formally and finally disposed of.[8]

In December 1979 Fraser promoted Carrick from the education ministry, appointing him Minister for National Development and Energy. Previously ranked nineteenth in the ministry, his new portfolio was the fifth most senior in Cabinet, and embraced responsibilities as diverse as national energy policy, minerals exploration, radioactive waste management, decentralisation and urban planning, and local government. Of these, the most pressing was energy policy. In May 1980 Carrick stated that recent events in the Middle East, particularly the Iranian revolution and the Russian invasion of Afghanistan, had ‘destabilised the world, so we must conserve… . We must get exploration going and above everything else we must stimulate the development of alternative fuels’. Carrick regarded full import parity pricing for domestic crude oil as the cornerstone of the government’s energy policy, asserting that full import parity pricing would encourage conversion from oil to natural gas, electricity and coal, thereby conserving existing supplies of petroleum fuels, promoting new exploration for oil and gas, and fostering development of alternative energy sources. He evinced particular interest in Queensland’s Rundle shale oil conversion project, describing it as ‘the greatest synthetic fuel enterprise in the world’. As world oil prices eased, and Rundle proved unviable on environmental and commercial grounds, Carrick turned his attention to advocating nuclear energy. In 1981 he chaired the governing board at ministerial level of the International Energy Agency (IEA) and, on IEA’s behalf, held informal talks on future oil pricing with OPEC’s Sheik Yamani.[9]

Carrick was appointed KCMG in January 1982. He moved to the backbench when the Hawke Labor Government took office in March 1983. From there he hammered away at the government’s economic management and brought his considerable experience of the electoral system to deliberations of the Joint Select Committee on Electoral Reform which sat constantly between 1983 and 1984. He dissented from a number of the committee’s recommendations, and advocated the abolition of compulsory voting.

Carrick retired from the Senate in June 1987. ‘I don’t miss Parliament,’ he told an interviewer from The Bulletin, ‘though I miss its intellectual stimulus.’ He re-engaged with policy advice in September 1988 after NSW Premier Nick Greiner invited him to chair a fourteen member committee, tasked with reviewing legislation governing New South Wales schools and recommending ways in which education could be improved in state and private schools. The committee embarked on ‘an unprecedented level of public consultation’, and its recommendations were substantially embodied in the NSW Education Reform Act 1990, described subsequently as ‘the most significant education legislation in New South Wales in the 20th century’. Carrick worked in a voluntary capacity on the original report and on the reviews of its implementation which he delivered in 1992 and 1994.[10]

Carrick was chairman of the Gas Council of New South Wales (1990–95), served on the executive committee of the Foundation for Aged Care (1990–2001) and the New South Wales ministerial advisory council for teacher education (1992–95), and chaired the Macquarie University Institute of Early Childhood Foundation (2000–08) and the advisory committee of the Gifted Education Research, Resource and Information Centre at the University of New South Wales (1991–2007). In August 2004 the newly-established Carrick Institute for Learning and Teaching in Higher Education was named in his honour (renamed the Australian Learning and Teaching Centre in 2007, it ceased to function in 2011). In 2008 Carrick was appointed a Companion of the Order of Australia for ‘distinguished service in the area of educational reform in Australia, particularly through the advancement of early childhood education and to the development and support of new initiatives in the tertiary sector’.

Although proud of his achievements, Carrick remained a modest man, imbued with the strong commitment to community service which he shared with so many other returned servicemen of his generation. Parliament had presented him with ‘a marvellous opportunity to do what [he] believed was right’. Yet he wondered whether he had made a greater contribution in his role as NSW Liberal Party general secretary, as manager ‘of a very large and difficult structure with enormous capacity to influence and shape the well-being of Australia’. Perhaps in recognition of Carrick’s self-effacing attitude, valedictory comments in the Senate on his retirement, while laudatory, were restrained. His old adversary, John Button, cited an article from the National Times in 1975 which described Carrick as ‘the closest approximation to a conservative intellectual in the [Fraser] cabinet’. Button acknowledged that Carrick’s ‘stringent approach’ and ‘intellectual discipline’ had made him ‘a very good minister’. Writing in 2010, John Howard described Carrick as ‘my political mentor. I learned more about politics from John than from any other person I have known’.[11]

[1] This entry draws throughout on a transcript of an interview with Sir John Carrick by Ron Hurst, 1987–91, POHP; ‘Questionnaire’ completed 10 Oct. 1982 for Parliament’s Bicentenary Publications Project, NLA MS 8806; Carrick, John Leslie, Officer’s Record of Service, AIF, NAA B 2458; SMH, 24 April 1998, p. 13; Emery Barcs, ‘The value of the individual’, The Bulletin (Syd.), 16 Jan. 1990, pp. 110–12.

[2] POHP; Ian Hancock, ‘John Carrick: the influence of head office’ in Ken Turner & Michael Hogan (eds) The Worldly Art of Politics, Federation Press, Syd., 2006, pp. 209–27; Ian Hancock, The Liberals: The NSW Division 1945–2000, Federation Press, Syd., 2007, pp. 66–7, 86–7, 118–137; J. L. Carrick, The Liberal Way of Progress, Liberal Party, NSW, Syd., 1949; Weekend Australian Magazine (Syd.), 9–10 June 1979, p. 2; The Bulletin (Syd.), 20 Jan. 1962, pp. 4–5.

[3] POHP; CPD, 8 Sept. 1971, pp. 543–8, 9 Sept. 1971, pp. 630–6, 9 March 1972, pp. 649–79, 8 May 1973, pp. 1396–400.

[4] SMH, 23 May 1973, p. 6; Information provided to the author by Sir John Carrick, 11 May 2007; CPD, 2 March 1972, pp. 439–40, 27 April 1972, p. 1397, 1 June 1972, p. 2423; Information provided to the author by Vicki Bourne, 11 Aug. 2009; CPD, 5 June 1987, p. 3685, 5 Oct. 1971, pp. 1143–9, 19 Oct. 1972, pp. 1733–7, 3701; John Button, As It Happened, Text Publishing, Melb., 1998, p. 183.

[5] CPD, 7 March 1974, p. 169; 8 April 1974, pp. 732–8, 10 April 1974, pp. 883–902; Sir Billy Snedden, An Unlikely Liberal, Macmillan, South Melb., 1990; Advertiser (Adel.), 22 Jan. 1976, p. 5; Harry Evans & Rosemary Laing (eds), Odgers’ Australian Senate Practice, 13th ed., Department of the Senate, Canberra, 2012, pp. 712–30; CPD, 28 Aug. 1975, pp. 364–8, 10 Sept. 1975, pp. 696–705, 1 Oct. 1975, pp. 879–83, 22 Oct. 1975, pp. 1342–7, 30 Oct. 1975, pp. 1633–41; POHP; Malcolm Fraser & Margaret Simons, Malcolm Fraser: The Political Memoirs, Miegunyah Press, Carlton, Vic., 2010, p. 290.

[6] CPD, 31 Aug. 1972, pp. 649–53; The Bulletin (Syd.), 27 March 1979, pp. 30, 32, 34; Wells Oration by Senator the Hon. J. L. Carrick, Canberra Grammar School, 1978; Committee of Inquiry into Education and Training, Report, Vol. 1; Canberra, 1979, POHP.

[7] Rodney Tiffen, Scandals: Media, Politics & Corruption in Contemporary Australia, UNSW Press, Syd., 1999; Patrick Weller, Malcolm Fraser PM, Penguin Books, Ringwood, Vic., 1989; Philip Ayres, Malcolm Fraser: A Biography, Heinemann, Melb., 1987, pp. 84–5; POHP.

[8] CT, 26 Nov. 2005, p. 11.

[9] CPD, 23 May 1980, pp. 2775–82, 26 Aug. 1980, pp. 342–8; National Times (Syd.), 28 Sept.–4 Oct. 1980, pp. 2–3; Australian Business (Melb.), 4 June 1981, pp. 98–9; John Carrick, ‘Shedding some light on the nuclear energy debate’, Australian Foreign Affairs Record, Vol. 53, No. 7, July 1982, pp. 479–80; POHP.

[10] CPD, 5 May 1983, pp. 236–40, 22 March 1985, pp. 656–61, 18 Feb. 1987, pp. 197–8; ‘Dissenting reports submitted by Senator the Hon. Sir J. Carrick, KCMG’, in Joint Select Committee on Electoral Reform, First Report, Canberra, Sept. 1983, pp. 223–39; Emery Barcs, ‘The value of the individual’, The Bulletin (Syd.),1990, p. 110–12; Report of the Committee of Review of New South Wales Schools, Syd., Sept. 1989; The Carrick Report Two Years On, Ministry of Education and Youth Affairs, Syd., July 1992; The Carrick Report Four Years On, Ministry of Education and Youth Affairs, Syd., October 1994; Geoffrey Sherington, ‘Education Policy’ in Martin Laffin & Martin Painter (eds), Reform and Reversal: Lessons from the Coalition Government in New South Wales, 1988–1995, Macmillan Education Australia, South Melb., 1995, pp. 179–87; John Hughes & Paul Brock, Reform & Resistance in NSW Public Education, NSW Department of Education and Training, Syd., 2008, pp. 132–62.

[11] POHP; CPD, 5 June 1987, pp. 3684–705; John Howard, Lazarus Rising, HarperCollins, Syd., 2010, p. 30.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, Vol. 4, 1983-2002, Department of the Senate, Canberra, 2017, pp. 31-37.