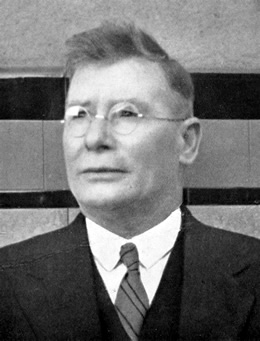

ARTHUR, Thomas Christopher (1883–1953)

Senator for New South Wales, 1938–44 (Australian Labor Party)

Christopher Thomas (later Thomas Christopher) Arthur, miner and union official, was born on 11 May 1883 at Forbes, New South Wales, the son of William John Arthur, miner, and his wife Phillipina, née King. After leaving school, Tom Arthur worked as a miner and a shearer, befriending such Labor luminaries as Jack Barnes and John McNeill, both of whom would attain high office in the Labor Party and the Australian Workers’ Union (AWU). Arthur traced his involvement in the Labor Party and the labour movement to the early 1890s.[1]

An organiser for the AWU, Arthur stood as a Labor candidate for the seat of Hawkesbury at the general election in New South Wales in March 1917, but was defeated in the first round of a three‑way contest. He was a vice-president of the central branch of the AWU from 1917 to 1924, and a delegate to AWU annual conventions (1917-21, 1923) and ALP conferences. He was also a member of the New South Wales ALP’s central executive between 1918 and 1922. In 1919 he was appointed a rural commissioner on the New South Wales Board of Trade (the body charged with formulating the basic wages and conditions of industry), holding the position until 1922. In 1923, however, he was embroiled in the ballot box scandal that erupted at the ALP state conference, undermining his standing in both party and union.[2]

In the late 1920s Arthur turned to mining in the western coalfield of New South Wales, becoming secretary and district delegate of the Lidsdale miners’ lodge. He stood unsuccessfully as a state Labor candidate for the Senate in 1931, following the split between Labor Prime Minister James Scullin and Labor Premier of New South Wales Jack Lang. The breach in Labor’s ranks temporarily healed, Arthur stood again in 1937, alongside Amour, Armstrong and Ashley—the ‘Four A’s’―winning the third seat in Labor’s clean sweep of the four Senate vacancies in New South Wales.[3]

Following his election, Arthur declared that he was looking forward ‘after June next year, to a term of useful and constructive work for the Labor Movement in the Commonwealth Parliament’, but was soon disillusioned by what he found. At a railway picnic at Lithgow on 14 November 1938, he told his audience: ‘This matter of being a Senator is merely a joke, and the sooner the policy of the Labor party to abolish the Senate is carried out the better for the country. Since September 26 we have sat for 15 days’. Inevitably, these remarks attracted the ire of Government senators. The Leader of the Government in the Senate, George McLeay, dismissed Arthur’s comments as ‘the asinine view of an “A” grouper from New South Wales, with which, I feel sure, not even his own party agrees’. Senator Dein argued that if ‘we accept the honorable senator’s words at their face value, he condemns himself as a senator’. Arthur was unrepentant, while the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate, Joe Collings, suggested that the problem lay with the Government: ‘For a long period this Senate has been treated as a joke by the government party in the matter of accommodation in this building . . . In the way government business in this chamber is dealt with, also, the Senate is treated as a joke’.[4]

Nonetheless, there he was; he generally spoke on issues of personal interest or on specific matters that had been drawn to his attention. In his first speech he justified the coalminers’ refusal to submit their case to arbitration and drew attention to the occupational hazards of mining and construction work, citing the effects of dust and hookworm. He presented a detailed proposal for the appointment of a health commission to investigate the issue. In 1939 he questioned what he saw as the undue influence of big business on bodies coordinating Australia’s industrial effort in the lead-up to World War II, and in a debate on international relations reminded the Government of its responsibilities under the International Labour Organization.[5]

With the outbreak of war Arthur became increasingly preoccupied with the affairs of Producers’ Oil Wells Supplies Ltd, an Australian oil exploration company of which he was a director. In December 1939 he raised the case of the company’s technical adviser, Max Steinbuchel, ‘an oil geologist . . . imported from the United States of America’, questioning the Government’s motives over Steinbuchel’s threatened deportation. Arthur believed that the ‘major oil companies are behind this move; they do not want flow oil to be discovered in Australia’. In April he declared his directorship of the company, and called upon the Government to support it with money and equipment, stating that ‘if that company does not produce petroleum in commercial quantities in twelve months . . . I shall be prepared to resign my seat in this chamber and not contest it again’.

Once again he questioned the motives of both Government and corporations, attacking the credentials of the members of the Government’s Oil Advisory Committee and presenting allegations of corruption in the oil industry. The following day, the Minister for the Interior, Senator Foll, replied:

The honorable senator’s speech was one of the most amazing to which I have ever listened in this chamber. It was amazing because the honorable gentleman used his privileged position as a member of this Senate not merely for the purpose of ventilating a personal grievance, which, of course, he had every right to do, but also for the purpose of ‘boosting’ a company with which, apparently he is actively associated. His attitude last night was most improper.

Dismissing Steinbuchel as ‘a diviner’, whose purpose was to relieve the gullible of their money, Foll suggested that £10 000 was ‘too high a price to pay in order to get Senator Arthur out of this chamber. I am sure that we shall be able to do that much more cheaply at the next election’. Arthur did not relent, making periodic attacks on both the Government and the oil industry, and continuing to defend Steinbuchel. In the meantime, he was involved in controversy with his fellow directors as the affairs of the company began to unravel.[6] His behaviour may have been linked to the effects of persistent heavy drinking. According to one observer, journalist Don Whitington: ‘Arthur was stupid from the effects of liquor most of the time he was in the Senate. Often he had to be helped into the Chamber for divisions. Sometimes he sat on the wrong side of the Chamber for a division and had to be rescued frantically by other Labor Senators’.[7]

Arthur failed to win ALP re-endorsement for the federal election of 1943. Standing as an independent, he was resoundingly defeated. Nevertheless, he remained loyal to the Curtin Government throughout the remainder of his term, assisting in the passage of important legislation, most notably the Coal Production (War-time) Bill 1944. In the absence of the UAP’s Senator Crawford the Government enjoyed a majority of one, and Arthur’s vote was vital to the passage of the bill. When, on the morning of the vote, Arthur went missing, the Government delayed the progress of the bill while a search was instituted. Don Whitington, who later made the astounding and unsubstantiated assertion that Arthur was the ‘only Australian politician ever abducted’, provided also an account of the senator’s subsequent recovery:

In a bedroom at the Hotel Canberra they found Arthur, his only companion a bottle of whisky. The amiable Senator allowed himself to be transferred, still with his bottle of whisky, to a room at Parliament House in the suite of Labor’s Senate Leader [Senator Keane]. There he spent the rest of the day, being assisted into the Chamber for divisions. And so the coal legislation was passed.[8]

As Arthur left the Senate, the President, Gordon Brown spoke in terms redolent of happier days: ‘Senator Arthur has been a tower of strength to the Labour movement for many years, and I shall never forget the effectiveness of his maiden speech in this chamber’. Arthur himself hoped to return: ‘I shall say not good-bye, but au revoir. The chances are that you will see me here again’.[9]

Tom Arthur retired to his home in the Sydney suburb of Clovelly, and died on 6 June 1953 at Rydalmere Mental Hospital. He was buried at Rookwood Cemetery two days later. On 31 May 1917 he had married Kathleen Annie O’Brien, at the Sacred Heart Church, Darlinghurst, according to the rites of the Roman Catholic Church. There was one son, John, who, with Kathleen, survived him.

[1] CPD, 23 June 1943, p. 270; Labor Daily (Syd.), 17 Nov. 1937, p. 4.

[2] SMH, 5 Mar. 1917, p. 8; Lithgow Mercury, 2 Mar. 1917, p. 3; AWU, Central Branch Membership Rolls, 1915-24, E154/46/1, Central Branch Minutes, N117/1484-1487, Minutes of Annual Conventions, 1917-23, M44, Noel Butlin Archives Centre, ANU; Australian Worker (Syd.), 13 June 1918, p. 5, 19 June 1919, p. 17, 17 June 1920, p. 5, 7 Apr. 1921, p. 5; CPD, 3 Apr. 1941, p. 624, 13 May 1942, p. 1082; Australian Worker (Syd.), 11 Oct. 1922, p. 12, 6 June 1923, p. 17, 13 June 1923, p. 17, 10 Oct. 1923, p. 18, 25 Feb. 1925, p. 20.

[3] Reports of Delegate Board Meetings, Western District, ACSEF, 1927-34, E165/34/2, Noel Butlin Archives Centre, ANU; Lithgow Mercury, 3 Dec. 1931, p. 4; SMH, 7 Dec. 1931, p. 10; Ross McMullin, The Light on the Hill: The Australian Labor Party 1891–1991, OUP, Melbourne, 1991, p. 198; SMH, 11 Nov. 1937, p. 8.

[4] Labor Daily (Syd.), 17 Nov. 1937, p. 4; Lithgow Mercury, 16 Nov. 1938, p. 6; SMH, 17 Nov. 1938, p. 11; CPD, 18 Nov. 1938, pp. 1703-13.

[5] CPD, 27 Sept. 1938, pp. 213-18, 12 Oct. 1938, pp. 617-18, 8 June 1939, pp. 1490-5, 14 June 1939, pp. 1783-5, 17 May 1939, pp. 401-4.

[6] CPD, 8 Dec. 1939, pp. 2530-5, 18 Apr. 1940, pp. 93-107, 19 Apr. 1940, pp. 177-83, 17 May 1940, pp. 978-9, 29 May 1940, pp. 1416-20, 30 May 1940, pp. 1537-8, 20 June 1940, pp. 9-12, 27 Nov. 1941, pp. 1061-2, 29 Sept. 1942, pp. 1029-31; SMH, 14 Mar. 1940, p. 9, 4 Apr. 1940, p. 10, 6 Feb. 1941, p. 3, 11 Feb. 1941, p. 5; Argus (Melb.), 30 Jan. 1941, p. 9, 11 Feb. 1941, p. 7.

[7] Don Whitington, Strive to be Fair: An Unfinished Autobiography, ANU Press, Canberra, 1977, pp. 75-6.

[8] CT, 10 July 1943, p. 2; SMH, 16 Sept. 1943, p. 7; Sunday Telegraph (Syd.), 26 Mar. 1944, p. 6; CT, 4 Mar. 1944, p. 3; Whitington, Strive to be Fair, p. 76; Don Whitington, Ring the Bells: A Dictionary of Australian Federal Politics, Georgian House, Melbourne, 1956, p. 6.

[9] CPD, 30 Mar. 1944, pp. 2325, 2328.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 2, 1929-1962, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic., 2004, pp. 435-438.