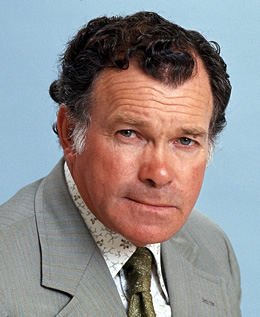

McLAREN, Geoffrey Thomas (1921–1992)

Senator for South Australia, 1971–83 (Australian Labor Party)

During his twelve years in the Senate, Geoff McLaren, an ‘old-fashioned’ Laborite, gained a reputation on both sides of politics as a very hard worker who took part in the Senate’s proceedings with great gusto. If not especially influential, he was never inconspicuous. Senator Watson once cited McLaren’s daily habit of reading the whole of the previous day’s Hansard, a practice, Watson considered, that other honourable senators could well emulate.

Geoffrey Thomas McLaren was born on 1 February 1921 in Koroit, a small town near Warrnambool in south-west Victoria. The eldest child of James McLaren, grocer, and Myrtle Ellen, née Salt, he left school during the later years of the Great Depression to take up a full-time job in the local general store. With little formal education or inclination to pursue it, he followed his father into shearing and, in the late 1930s and early 1940s, travelled around south-eastern Australia (including Tasmania) in search of work. In off seasons, he would earn money doing manual work, such as digging potatoes and picking fruit. In 1935 he joined the Australian Workers’ Union, in which he became a union ‘rep’. During World War II, McLaren joined the Citizen Military Forces, enlisting on 5 June 1941. On 19 July he married Florence Beryl Jennings, from Tarragal near Portland, at the Presbyterian Manse, Footscray. From April 1942 until October 1943, McLaren served with the 2nd Field Ambulance in Western Australia. He was discharged on 1 March 1944.

Between 1941 and 1945 Geoffrey and Beryl had three children. By this time, the qualities that allowed McLaren’s later political career had become apparent. He was a valued shearer, not so much because he was quick, but because he was competent, hardworking and reliable. His loyalty to his wife, his party and the trade union movement never wavered. His working-class background and his experiences as a young man instilled in him a sympathy for working people and at least a suspiciousness toward those much better off than himself. He was intensely conscious of differences in social status and was scornful of—and later in Parliament hostile toward—those who seemed to him to look down on so-called ‘ordinary’ people. His aggressive egalitarianism was apparent in his disdain of titles. He refused to use them and, at least from the mid-1970s, strenuously objected whenever Hansard tried to insert ‘Sir’ in front of any of his many references to John Kerr. One of the senators he most admired, and whom he was very much like, was Jim Cavanagh, who was eight years his senior.[1]

In 1950 the McLarens moved to South Australia and settled in Murray Bridge, the base from which he did his shearing and where he lived the rest of his life. Here, in off seasons, he established a reputation as an industrious and meticulous jack of all trades, particularly in the building industry. Several well-known premises in Murray Bridge are at least partly the product of his labour. Like most members of the ALP since its inception in the early 1890s, McLaren saw no contradiction between, on the one hand, being an active union member and even calling himself a socialist and, on the other hand, becoming a small businessman. In the early 1960s, he and his wife went into the poultry business (hence his nickname ‘Feathers’) and in July 1963 established the Golden Yolk Poultry Farm. Throwing himself into the egg producers’ campaign to introduce orderly marketing into the egg industry, he became chairman of the poultry section of the Murray Bridge United Farmers and Graziers of South Australia.

Yet he remained as committed as ever to the ALP. In the early 1950s, he helped revive the Murray Bridge sub-branch of the party, becoming its vice-president, and from 1957, its president, a position he retained until he left the Parliament, thereafter continuing as a delegate to the state council. Only in the late 1960s did the prospect of a career in politics arise. In 1968 he contested a seat in the Legislative Council of South Australia for the ALP but was neither enthusiastic about standing nor hopeful of winning. However, his loyalty and dedication to the party, coupled with his commitment to unionism and success in business, must have impressed the party hierarchy because in 1969 he was endorsed as an ALP candidate for the forthcoming Senate election. This was a turning point in his life. There was a keen preselection battle, and one of those McLaren defeated for third place on the ALP ticket was John Bannon, then a rising star in the South Australian branch. McLaren often quipped that if he had not won the preselection contest, Bannon would have gone into federal politics and never become premier of South Australia.[2]

At the Senate election of November 1970, McLaren won the fifth seat, defeating an independent candidate after securing the bulk of the preference votes from the Liberals’ Martin Cameron. McLaren took up his seat in July 1971. Throughout his years in the Senate he raised issues concerning his constituents living in and around Murray Bridge, country people in particular and South Australians in general. But his name is associated less with the major questions of the day than with his activities in and about the Senate. From the start, he showed a tendency to take on unusual, if not seemingly trivial, issues and to engage in flamboyant actions. In November 1971, McLaren, with the ALP’s senators Poyser and Keeffe, prompted a wave of publicity by wearing shorts into the Senate. McLaren then asked the President of the Senate, Sir Magnus Cormack, whether there was anything in standing orders to prohibit honourable senators from ‘taking their places in this chamber neatly attired in shorts, shirts and knee length hose, as is now permitted in the South Australian Parliament’. The President referred the matter to the Senate House Committee, which declared the wearing of shorts to be not in accord with the dignity of the Senate chamber, a conclusion adopted by the Senate on 29 February 1972. Mildly rebuked, the three recalcitrants subsequently relented, but McLaren persisted in pursuing what he called ‘dress reform’, and was still in the Senate when safari suits were adopted as a compromise to the wearing of shorts.

In October 1972, he announced that he would boycott a ceremony in the Senate because it involved the presentation of a sword to the Usher of the Black Rod. To the President of the Senate, he declared his disappointment that the Senate would associate itself with a ‘symbol of death’. There is no reason to believe that McLaren was not genuinely passionate about these issues. As he said years later: ‘I’m opposed to all the ceremonial gatherings and the wearing of monkey suits and all this regalia’. However, his persistence reveals not only his preoccupation with parliamentary procedures but also his eagerness to win publicity for himself and his party—and to embarrass the Fraser Government. In Question Time, he was prolific with questions and notices of motion, but it was his participation in adjournment debates that became legendary. Time and again, he forced the Senate into late-night sittings, to the annoyance of all sides. On the occasion of McLaren’s departure from Canberra, fellow Labor senator, John Button, remarked that ‘honourable senators will probably get to bed earlier now’.[3]

In May 1979 McLaren was suspended from the sitting of the Senate after refusing to withdraw what were ruled to be offensive words: in the course of a robust attack on the Fraser Government, he had quoted a newspaper headline, ‘Lies, lies, lies!’ The ruling was the subject of an unsuccessful motion of dissent, Opposition speakers emphasising the practical difficulties involved if contentious published words could not be quoted. But both the Privileges and Standing Orders committees confirmed that, ‘in quoting a document, a senator is not permitted to utter words which would not be permitted under the rules of debate if uttered in the normal course of speaking’.

McLaren’s energy and persistence were just as evident in his committee work. Between 1973 and 1983, McLaren served on nine Senate committees, five of which were estimates committees. He was relentless in his aggressive questioning of ministers, the Liberals’ Fred Chaney later stating that he would not miss McLaren at estimates committee hearings, or ‘in any of the debates in this place’, but that he would certainly miss him around Parliament House. Senator D. B. Scott, the leader of the National Party in the Senate, was equally enigmatic when he remarked that McLaren’s was ‘a voice that none of us will forget, whether in this chamber or in an Estimates committee’.

Despite such backhanded compliments, even McLaren’s detractors had to admit that he was not merely tenacious, he was well informed. In everything he did, he had a penchant for documentation and an eye for detail. McLaren built up an elaborate filing system and what he did not have on paper he retained in his mind. Some senators recalled his entering the chamber with papers ‘at least a foot high’, while others remembered that he was ‘a great terrier for and fossicker of information’. He was never slow to speak. Veteran Canberra journalist Alan Ramsey recalled that he ‘could talk the paint off the walls’. On one occasion McLaren was the butt of senatorial ‘humour’, when his party room noticeboard contained a fake press item calculated to provoke him to give a speech in the Senate on the subject, which he did. Later, he sadly complained to one of the parliamentary clerks that the other senators ‘played a joke on me’.

But what did McLaren achieve as a senator—apart, of course, from frustrating and irritating both sides of politics? Here Ramsey is one of the very few who spoke up for him. Many senators would have been able to recall that, in the early 1980s, in his wholehearted campaign as a lowly backbencher to ‘get at’ the Government, McLaren pursued a personal crusade against the economic privileges that several of Fraser’s Cabinet colleagues enjoyed by virtue of their continued re-election to Parliament. Liberals like Tony Street and particularly National Party ministers Doug Anthony, Ian Sinclair and Peter Nixon, were embarrassed by McLaren’s claims that they enjoyed extraordinary ‘rorts’, such as ‘huge’ travel allowances. After Labor was returned to power in March 1983, the Hawke Government established what became known colloquially as the ‘perks and lurks register’—a collation of figures that annually revealed exactly what amounts parliamentarians were spending on themselves and their support staff. Such expenses continued to rise, but at least they could be publicly scrutinised.[4]

As a senator, McLaren tended to see his constituency as including everyone in South Australia who did not live in the metropolitan area. When he set up his office in Murray Bridge, he became the first senator in the state to establish his base outside Adelaide’s central business district and a few years later he set up another in the south-eastern town of Mount Gambier. His interest in and trips to the Northern Territory before it was represented in the Commonwealth Parliament earned him the informal title of the ‘senator for the Northern Territory’. He travelled to, and established contacts in, many of South Australia’s non-metropolitan areas, but the Riverland was clearly his main concern. Scott remarked of him that he was ‘probably the greatest promoter of Murray Bridge, and indeed the River Murray’, that he could recall. Always an early riser, McLaren would also often work late into the night, particularly on the regular newsletter he distributed to constituents.

Notwithstanding his committee and constituency work, about which he was unusually conscientious and industrious, McLaren allowed himself to enjoy some of ‘the perks’, such as overseas trips to conferences in Czechoslovakia and East Germany, also to Venezuela and Fiji. He had two study tours to Canada and one to the Soviet Union. In fact, if his former life as a shearer infected him with the travel bug, his mid-life career as a senator nurtured it. After leaving the Senate, he and his wife travelled all over Australia with a caravan, among other things revisiting Canberra and attending the ALP centenary celebrations in Barcaldine in outback Queensland.[5]

McLaren’s parliamentary career was unexpectedly terminated by the sudden and dramatic events of 3 February 1983, which witnessed not only the announcement of a double dissolution the following month but also the change in the leadership of the Federal Parliamentary Labor Party from W. E. Hayden to R. J. Hawke. The South Australian branch dropped McLaren from its Senate ticket, ostensibly because he would be over its age limit before he finished another term. Like the good party man he was, he left without complaint, but he believed his loyalty to Hayden over Hawke was a reason for his failure to win another preselection. Ironically, while he had been elected to the Senate four times—in 1970, 1974, 1975 and 1977—he had never been able to serve out a full six-year term.

McLaren died in the Murray Bridge Hospital on 30 January 1992. Married for fifty years, he was survived by Beryl and their children. Throughout his life he had looked after his physique and health, and remained fit and energetic. A talented cyclist in his youth, he took a keen interest in sport thereafter and was the manager of a local Australian Rules football team for several years. Former MHR Clyde Cameron remembered McLaren as nice looking, of medium height and lean build, with a full head of hair. McLaren’s assertive behaviour in parliamentary debates belied the fact that he was a modest and rather shy man. His entries in Who’s Who in Australia between 1974 and 1983 provided only his name and address.[6]

[1] SMH, 29 Aug. 1992, p. 23; CPD, 25 Feb. 1992, p. 42; Herald (Adel.), Autumn 1992, p. 23; Murray Valley Standard (Murray Bridge), 27 Feb. 1992, p. 8; Geoffrey Thomas McLaren, Transcript of oral history interview with Tony Hannan, 1988, POHP, TRC 4900/71, NLA, pp. 1:23, 1:29–30, 2:2, 2:18, 2:23, 2:29–30, 8:11–12; McLaren, Geoffrey Thomas—Defence Service Record, B884, V170220, NAA; Age (Melb.), 3 Dec. 1982, p. 1.

[2] Murray Valley Standard (Murray Bridge), 27 Feb. 1992, p. 8; Herald (Adel.), Autumn 1992, p. 23; CPD, 25 Feb. 1992, p. 45; United Farmers and Graziers of South Australia, Poultry Committee minutes, 1966–68, N18/143, Australian Primary Producers’ Union note of interview, 22 Apr. 1968, N18/146, NBAC, ANU; McLaren, Transcript, pp. 3:2, 3:5, 9:26.

[3] Murray Valley Standard (Murray Bridge), 27 Feb. 1992, p. 8; CPD, 25 Feb. 1992, p. 38; Advertiser (Adel.), 12 Nov. 1971, p. 1; CT, 12 Nov. 1971, p. 8; SMH, 4 Nov. 1971, p. 3, 5 Nov. 1971, p. 8, 20 Nov. 1976, p. 1; McLaren, Transcript, pp. 5:13–18, 8:12–13; CPD, 3 Nov. 1971, p. 1605, 11 Nov. 1971, p. 1867, 23 Nov. 1971, p. 1973, 2 Dec. 1971, p. 2383, 8 Dec. 1971, pp. 2483–4; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 12 Nov. 1971, p. 3; Herald (Melb.), 3 Oct. 1972, p. 1; Australian (Syd.), 6 Oct. 1972, p. 9; McLaren, Transcript, p. 8:14; CPD, 3 May 1983, p. 141, 25 Feb. 1992, pp. 37, 39, 3 May 1983, p. 132; McLaren, Transcript, pp. 8:24–5, 8:29–30.

[4] CPD, 29 May 1979, pp. 2259–70; Harry Evans (ed.), Odgers’ Australian Senate Practice, 12th edn, Department of the Senate, Canberra, 2008, pp. 194–5; CPD, 3 May 1983, pp. 132, 134, 136, 139, 25 Feb. 1992, pp. 43–4; SMH, 29 Aug. 1992, p. 23; McLaren, Transcript, 8:5–9; SMH, 13 Nov. 1981, p. 10.

[5] CPD, 3 May 1983, p. 139; Herald (Adel.), Autumn 1992, p. 23; CPD, 25 Feb. 1992, pp. 41–2, 44–7, 3 May 1983, pp. 136, 140–2; Border Watch (Mount Gambier), 7 Aug. 1981, p. 3; Northern Territory News (Darwin), 18 Apr. 1972, p. 3; McLaren, Transcript, pp. 3:9–12, 5:22–3, 5:30–1, 6:1–4, 7:24, 7:27–9, 9:29, 10:2, 10:27.

[6] Advertiser (Adel.), 8 Feb. 1983, p. 1, 9 Feb. 1983, p. 31; McLaren, Transcript, pp. 1:16–17, 3:26–7, 4:14–16, 4:23–4, 4:28–9, 9:9–18, 9:26, 10:28–9; Herald (Adel.), Autumn 1992, p. 23.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 3, 1962-1983, University of New South Wales Press Ltd, Sydney, 2010, pp. 255-259.