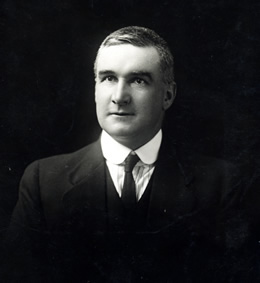

GRANT, Charles William (1878–1943)

Senator for Tasmania, 1925, 1932–41 (Nationalist Party; United Australia Party)

Charles William Grant, businessman, was born on 24 April 1878, at Hobart, elder son of Charles Henry Grant, engineer, businessman and MLC, and Jane, née Nicholls. Educated in Hobart at The Hutchins School, Grant worked on various mainland sheep stations for a few years, returning to Hobart to commence a business career in 1901. In time he became a partner in the dairy produce firm of Murdoch Brothers. In the small world of Hobart finance, Grant seems to have become a giant, with widespread financial interests. Apart from holding down a host of directorships, he was chairman of directors of many firms including the Hobart Gas Company, Heathorn and Company, Motor Vehicles Ltd, and the Cascade Brewery Company. He was also a director of Davies Brothers, proprietors of the Hobart Mercury.[1]

In June 1922 Grant was elected to the Tasmanian House of Assembly as a Nationalist for the seat of Denison. He participated in the downfall of the Nationalist Government of Sir Walter Lee in October 1923, and its replacement by the Labor Government of J. A. Lyons. Grant later attributed his actions to a desire to put the interests of Tasmania before the interests of party—a theme that recurred throughout his career—and felt vindicated in having done so. The price he paid was narrow defeat in the state election of June 1925; his reward was being selected ahead of Lee, in July 1925, at a joint sitting of the two houses of the Tasmanian Parliament, for the Senate casual vacancy caused by the resignation of George Foster. The Mercury thought it significant that Grant’s selection ‘was, in the main, by members of both Houses of the State Parliament, who had experience of him in his capacity of legislator, and had learned to appreciate his value in a manner denied to the ordinary elector’.[2]

Grant’s first foray into federal politics was brief. Taking his seat in August 1925, he was defeated, amidst a large field of Nationalist candidates, in the November general election. He returned to business, travelling abroad to investigate the marketing of Tasmanian products, particularly fruit, in Britain and Europe. In June 1928 he was re-elected to the Tasmanian lower house. Such was his political standing, he was immediately made an Honorary Minister in the Nationalist Government of J. C. McPhee, who attributed the appointment to Grant’s ‘financial knowledge and experience’. Grant was to prove his worth as a financial adviser to McPhee at meetings of the Loan Council, ‘where his knowledge of financial matters . . . gained him a reputation’.

In March 1932 Grant was again selected to fill a casual vacancy in the Senate, caused, on this occasion, by the death of James Ogden. Once again, with Labor’s support, he narrowly defeated Lee. Resigning from the House of Assembly and taking his seat in the Senate, he immediately put forth the Tasmanian Government’s case against the Financial Agreements Enforcement Bill, which was designed to make the Lang Government in New South Wales meet its financial obligations. The Tasmanian Government believed the bill undermined the very principle of Federation—the sovereignty of the Commonwealth and the states in their respective spheres—although Grant was the only one among the six Tasmanian conservatives to vote against it. He retained his Senate seat in the general election of 1934, and held the position of temporary chairman of committees from 1935 to 1939, but from mid-1938 his attendance was curtailed by illness.[3]

Grant’s Senate career was noted less for his political vision than for the practical, though usually brief, contributions he made to debates on a wide range of subjects. Particular interests that reflected his business background included taxation, bankruptcy, exchange questions and the level of interest rates. A common theme was the need for economy in government. His, in fact, was a simple approach to government finances, illustrated in his declaration to the Senate that he did not believe in borrowing, and his assertion that governments should build only those public works that they could afford. He attacked the River Murray waters scheme, which he believed was too costly and of no apparent benefit to the nation. He scorned the League of Nations, a body he described as having no power and to which no one listened, suggesting that Australia’s financial contribution to that organisation would be better spent at home. On the other hand, Grant urged greater spending on defence and greater self-reliance. In 1934 he described Australia’s defences as ‘wholly inadequate’, and in 1937 urged rearmament. In 1938 he addressed various proposals designed to facilitate readiness for war.[4]

Grant was also concerned to protect Tasmania’s place in the Federation. A particular target, as with other Tasmanian senators, was the Navigation Act with its deleterious effects upon shipping between Tasmania and the mainland, but he also defended Tasmania’s fruit growers and attacked the poor quality of such services to the island as radio news. Grant’s views on Commonwealth–state relations showed a keen awareness of the direction that the Federation was heading: ‘I consider that the Commonwealth is overriding the provisions inserted in the Constitution for the protection of the States’. He suggested annual grants to Tasmania, the size of which should be known in advance, in preference to annual assessments by the Commonwealth Grants Commission. He lamented the effective demise of section 94 of the Australian Constitution, which dealt with surplus revenue, the reinstatement of which he believed would be a ‘godsend’ to the smaller states.[5]

As a conservative politician Grant was a member of the Royal Empire Society and in 1925 was active in the formation of the Tasmanian Rights League, an organisation committed to the protection of Tasmania’s interests within the Federation, if not its secession from the young nation. Grant was a staunch defender of the rights of the Senate against offhand treatment by the House of Representatives. He complained about the Commonwealth’s accrual of power by its increasing use of regulations instead of legislation, and noted, in 1938, that so many regulations were being gazetted that senators had great difficulty in considering them all. On the same occasion, he took exception to remarks by the federal Treasurer, Richard Casey, that if there were ‘a place for women in politics it is probably in the Upper House or in the Senate, where things are quieter and the old gentlemen occasionally drowse in their beards’. Grant did not stand for election in 1940. At the time of his leaving the Senate, fellow Tasmanian and President of the Senate, J. B. Hayes, remarked that Grant was ‘held in the highest esteem, both in Tasmania and in Canberra’, and praised his ‘outstanding work in the Commonwealth and Tasmanian Parliaments’.[6]

On 10 June 1903 Grant had married Charlotte Bell, born in Aberdeen, Scotland, the daughter of Charles Bell, a Presbyterian minister, and his wife Jessie, née Yule; the ceremony was conducted at St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, Wagga Wagga, New South Wales. Grant died on 14 December 1943 in the house in which he was born at 350 Davey Street, Hobart. A warden of St Raphael’s Church, Fern Tree, and a well-known clubman in Hobart, Grant had been a member of the Tasmanian Club, the Athenaeum Club and the Royal Autocar Club of Tasmania. His funeral, followed by cremation at Cornelian Bay, was attended by many with whom he had been associated in business and politics, the list of mourners representing a substantial cross-section of Hobart’s commercial life, as well as Senator Hayes and Senator Darcey. Grant was survived by his son Harry and three married daughters, Mrs D. McDougall, Mrs J. B. Hamilton and Mrs G. K. Miller. Charlotte, herself a prominent figure in Tasmanian society, had died in 1938.[7]

As a man who made his name in business before choosing to take on the public duties of a member of Parliament, Grant was the type of politician once so common, but later much rarer in the nation’s parliaments.

[1] Mercury (Hob.), 15 Dec. 1943, p. 3; The Hutchins School Centenary Magazine 1846–1946, Hobart, [1946], p. 82.

[2] CPD, 31 Oct. 1934, p. 69; Mercury (Hob.), 13 May 1925, pp. 7–8, 8 June 1925, p. 7, 30 July 1925, p. 6.

[3] CPD, 14 Aug. 1925, p. 1444; Mercury (Hob.), 15 Dec. 1943, p. 3, 16 June 1928, p. 9, 3 Mar. 1932, p. 9; CPD, 10 Mar. 1932, pp. 892-4, 915.

[4] CPD, 8 Nov. 1932, pp. 2006-7, 2 Oct. 1935, pp. 387-8, 8 Sept. 1937, p. 714, 9 Nov. 1932, p. 2088, 5 Dec. 1933, p. 5486, 24 Oct. 1933, pp. 3803–4, 3 Oct. 1935, p. 476, 12 Dec. 1934, p. 1061, 31 Oct. 1934, p. 69, 8 Sept. 1937, p. 715, 4 May 1938, pp. 776-8.

[5] CPD, 27 Aug. 1925, pp. 1769-72, 2 Aug. 1934, p. 1185, 31 Oct. 1934, p. 71, 4 Apr. 1935, pp. 708-10, 6 Dec. 1933, pp. 5560-1, 2 Oct 1935, p. 388, 8 Sept. 1937, p. 716, 3 Oct. 1935, pp. 475-6, 13 Nov. 1936, pp. 1832-6, 23 Oct. 1935, p. 964, 24 Oct. 1933, p. 3804.

[6] Mercury (Hob.), 15 Dec. 1943, p. 3; Lloyd Robson, A History of Tasmania, vol. 2, OUP, Melbourne, 1991, pp. 399-400; Mercury (Hob.), 24 Apr. 1925, p. 7, 16 May 1925, p. 9; CPD, 1 June 1938, pp. 1597, 1602-3, 27 June 1941, p. 562.

[7] CPD, 9 Feb. 1944, pp. 4–5, 10–11; Mercury (Hob.), 15 Dec. 1943, p. 3, 16 Dec. 1943, p. 14, 9 Apr. 1938, p. 15.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 2, 1929-1962, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic., 2004, pp. 197-200.