EWING, Norman Kirkwood (1870–1928)

Senator for Western Australia, 1901–03 (Free Trade)

Norman Kirkwood Ewing served in three parliaments and stood for a fourth, but is remembered as a judge. Born on 26 December 1870 at Wollongong, New South Wales, he was the tenth child of a Church of England clergyman, Thomas Ewing, and his wife Elizabeth, née Thomson. His eldest brother (Sir) Thomas was a New South Wales MLA (1885–1901) and Commonwealth MP (1901–10), serving in Deakin’s second cabinet (1905–08). Another brother, John, was a Western Australian MLA (1901–04, 1905–08) and a member of the Legislative Council (1916–33) and Cabinet Minister (1923–24). Norman was educated at Illawarra College (Wollongong), Oaklands (Mittagong) and night school.

Having served articles with M. A. H. Fitzhardinge, he became a solicitor at Murwillumbah in New South Wales in 1894, and in 1895 unsuccessfully contested The Tweed seat in the New South Wales Legislative Assembly against the sitting member, J. B. Kelly. Attracted by the gold rush to Western Australia, he was admitted to the Bar in 1896, probably without all the necessary qualifications. In 1897, he established the firm of Ewing and Downing in Perth and published: The Practice of the Local Courts of Western Australia. In the same year, he won the Swan seat in the Western Australian Legislative Assembly as an Independent with 38 per cent of the poll against three supporters of Sir John Forrest’s ministry who split the vote. He completed a good year by marrying, on 15 October 1897, Maude Louisa, daughter of (Sir) Edward Stone, then senior puisne judge and later chief justice of Western Australia.[1]

Between 1897 and 1900, Ewing usually sided with the Opposition against the Forrest Government. He spoke against alien labour and in favour of one man one vote, women’s suffrage and divorce reform, and the use of contract labour by government departments. He opposed the notion that women and men sit in separate parliamentary chambers to reflect their different interests. He warmly supported Federation, was an executive committee member of the Federal League of Western Australia, and gained enough prominence to win the sixth place in voting for the first Senate in 1901, thus securing election for three years as a Free Trader.[2]

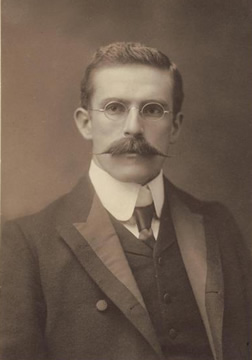

Possessing distinctive ‘aquiline features’, Ewing already wore glasses and sported a heavy waxed moustache. He was one of the first to speak at the opening session of the Senate, characteristically using a procedural motion on balloting for the Senate presidency to remind his hearers of the difficulties confronting members from outlying states. It was a favourite theme for one whose annual legal practice fell from an annual £3000 to £800 through long absences in Melbourne. Although he agreed that ‘it was the duty of members of the Senate to place the interests of the Commonwealth of Australia before the interests of the various States’, he was a strong advocate of the Senate’s right to discuss appropriation bills. He did not consider that the presence of organised political parties in the Senate invalidated its role as a States’ House, arguing that the membership reflected a cross-section of opinion within each state. Several of his interventions addressed legal technicalities on issues such as privilege and copyright laws. He believed that the Senate’s ‘power over the purse … should be preserved to the utmost’, and on one occasion brought a dictionary into the chamber to verify the meaning of the word ‘ordinary’, as used in section 53 of the Constitution. Although a Free Trader, he was far from respectful towards his leader, Sir Josiah Symon, ‘who says practically to us every time he speaks, that he knows better than we do’. After annoying Sir John Forrest by running down Western Australia’s agricultural potential, Ewing conceded that it might be improved in some circumstances: ‘A shower of rain every day of the week, and a shower of shit on Sundays’.[3]

By 1902, he was a frequent absentee from the Senate, the tyranny of distance proving too great. ‘My business is simply going to the devil’, he informed Alfred Deakin in October 1902, foreshadowing his resignation, and asking to be solicitor for the Commonwealth in Western Australia. Deakin refused. Ewing postponed his resignation until 17 April 1903 to ensure that Premier Walter James would not replace him with ‘a Protectionist Labor man’, but his heart was already back in local politics. He stood unsuccessfully both for mayor of Perth in November 1902 and as an Independent for the Legislative Assembly seat of Canning at the 1904 elections.[4]

These disappointments, and his wife’s persistent asthma, persuaded Ewing to move to Hobart. In 1906, he established the firm of Ewing and Seager. He stood for the Senate as an Anti-Socialist in December 1906 and was beaten narrowly. In 1907, he was active in the formation of the Progressive League, an organisation founded to invigorate anti-Labor politics, and in 1909 won election to the House of Assembly as an Anti-Socialist and one of the six members for Franklin. Almost immediately he engineered a coup against his leader, Sir Elliott Lewis, thus enabling John Earle to form the first Tasmanian Labor Ministry for a week in October 1909; but Lewis was restored, and Ewing remained a backbencher for five years, partly because politics often took second place to his thriving practice at the Hobart Bar. Following Labor’s victory under Earle and the death in October 1914 of A. E. Solomon, Ewing became Leader of the Opposition. His mildness in this role could be justified by the exigencies of wartime. Few cavilled when on 23 September 1915 the Earle Labor Government appointed him to a vacancy on the Supreme Court, since his leadership at the Bar had recently been recognised by appointment in 1914 as one of Tasmania’s few King’s Counsels.

By now clean-shaven and looking the part, Ewing at first seemed a sufficiently conformist judge, though more given than most to making comments from the bench. Although his service on a royal commission on the public debts sinking funds had to be terminated on his elevation to the bench, he served as royal commissioner in 1916 on the conduct of the Hobart licensing bench, and in 1918 on the professional qualifications of the surgeon-superintendent of the Hobart General Hospital, Dr V. R. Ratten (in whose favour he found, and who ten years later sent a wreath to Ewing’s funeral). His main professional interest was the codification of the Tasmanian criminal law, and although some of his ideas had to be modified in light of criticism from the parliamentary draftsman’s office, they formed the basis for the code piloted through Parliament in 1924 by his former clerk, Attorney-General A. G. Ogilvie.

During 1919 and 1920 his reputation became contentious. In 1918, Ewing had proposed that he move to Launceston, but on a higher salary, in effect answering the local call for a resident judge in that city. Then in 1919, the Commonwealth Government appointed him royal commissioner to inquire into the Northern Territory unrest, which culminated in the ousting of the Administrator, Dr J. A. Gilruth. Ewing’s findings were unexpectedly critical of Gilruth and his colleagues. He offended conservatives further by undertaking another royal commission for the New South Wales Government which led to the release of most of the Industrial Workers of the World sympathisers who had been convicted on dubious charges of arson in 1916. In November 1920, he sentenced a police constable to seven years’ imprisonment for shooting an illicit crayfisherman who attempted escape. After a hullabaloo in the Mercury, the Government commuted the sentence to three months.

Ewing was on good terms with Lyons’ Labor administration, and from 30 November 1923 to 13 June 1924 was Administrator of Tasmania, his senior colleagues on the bench being unavailable through illness or reluctance. Shortly afterwards, he suffered a stroke. He continued intermittently on the bench until shortly before his death, serving in 1925 as royal commissioner into the administration of the Tasmanian institute for the blind, deaf, and dumb. He died at Launceston on 19 July 1928 and was buried at the Carr Villa Cemetery. He left a son, Edward, and an adopted daughter, Doris, another daughter, Ethel, having died in an accident some years earlier.[5]

Both as politician and judge, Ewing played something of a lone hand with an eye to the main chance. If his findings in later life sometimes suggested superficiality, he was undoubtedly capable of meticulous attention to detail, and his part in reforming the criminal code is probably his most considerable achievement.

[1] Richard Ely (ed.), Carrel Inglis Clark: The Supreme Court of Tasmania: Its First Century, 1824–1924, University of Tasmania Law Press, Hobart, 1995, pp. 177–187, 217; Stefan Petrow, ‘Modernising the Law: Norman Kirkwood Ewing (1870–1928) and the Tasmanian Criminal Code 1924’, University of Queensland Law Journal, vol. 18, no. 2, 1995, pp. 287–304.

[2] WAPD, 29 November 1897, pp. 652–653, 3 October 1899, pp. 1538-1540, 1 December 1897, pp. 753–754, 8 December 1897, pp. 937–939, 21 June 1898, pp. 47–52, 2 November 1899, pp. 2107–2108.

[3] Scott Bennett, ‘Ewing, Norman Kirkwood’, ADB, vol. 8; CPD, 9 May 1901, p. 11; Deakin Papers, MS 1540, 14/231, NLA; CPD, 20 June 1901, pp. 1310–1317, 1336–1337, 19 June 1901, p. 1199, 3 July 1901, p. 1952, 15 August 1901, p. 3761, 6 September 1901, p. 4609, 26 June 1901, p. 1574; Frank C. Green, Servant of the House, Heinemann, Melbourne, 1969, p. 11.

[4] Correspondence between Senator Ewing and Alfred Deakin, 17 October 1902, 12 November 1902, Deakin Papers, MS 1540, 14/231, 239, NLA; Letters, Ewing to Senator Sir Josiah Symon, 23 February 1903, 8 April 1903, Symon Papers, MS 1736, 10/230, 233, 252, NLA.

[5] Bennett, ‘Ewing, Norman Kirkwood’, ADB; P. M. Weller, ‘The Organisation of Early Non-Labor Parties in Tasmania’, THRAPP, vol. 18, no. 4, October 1971, pp. 137–148; Petrow, University of Queensland Law Journal, 1995; D. J. Murphy (ed.), Labor in Politics: The State Labor Parties in Australia 1880–1920, UQP, St Lucia, Qld, 1975, pp. 412–427; Ely, Carrel Inglis Clark, pp. 177-87; CPP, Report of the royal commission on Northern Territory administration, 1921; NSWPP, Report of the royal commission into the trial and conviction and sentences imposed on Charles Reeve and others, 1920; Mercury (Hobart), 20 July 1928, p. 9; Examiner (Launceston), 20 July 1928, p. 7; Weekly Courier (Launceston), 25 July 1928, p. 47; Australian Worker (Sydney), 25 July 1928, p. 1.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 336-339.