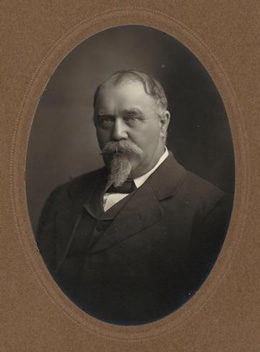

VERRAN, John (1856–1932)

Senator for South Australia, 1927–28 (Nationalist Party)

John Verran, miner, preacher, temperance advocate and politician, was a bluff, fiery man, short and stout, but of great physical strength. A twin son of John Spargoe Verran, copper miner, and his wife Elizabeth Jane, née Harvey, he was born at Gwennap, Cornwall, England, on 9 August 1856. In 1857, the family migrated to South Australia’s copper mining town of Kapunda, moving on after several years to new copper mines at Moonta. Verran was largely self-educated, having had only a few months of elementary schooling before beginning work in the mines at the age of ten. He learned to read with the encouragement of Moonta’s ministers of the Primitive Methodist Church; headmasters later came to his house to refine his grammar. Verran himself recognised the critical influence of the Primitive Methodists in shaping his political development. His quip, ‘I am an M.P., because I am a P.M.’, pointed to the years he spent as a local preacher. A Christian socialist and keen trade unionist, he believed that ‘the Church was not going to save men’s souls while their stomachs were empty’.[1]

Verran first entered politics in 1896, standing as a Labor candidate for the seat of Wallaroo. He was defeated, as he was again in 1899, but in 1901 won the seat at a by-election. One of the few survivors of Labor’s electoral debacle in 1902, he was elected leader of the Labor Party, on the death of Premier Tom Price, in 1909. Verran became Premier, Commissioner of Public Works and Water Supply, and Minister of Mines in the first all-Labor Government in South Australia following the election of 1910. This success prompted the formation of the Liberal Union, a fusion of the competing non‑Labor parties, who now accepted the discipline of a party pledge.

Verran’s success was short-lived, his government’s program of reform curbed by the conservative Legislative Council. Central to that program was reform of the Council itself, but attempts to limit its power—along lines which had succeeded with the House of Lords—failed, and Verran resorted to pleading with the British Government to pass imperial legislation to amend South Australia’s Constitution. Forced to exhaust all local constitutional means first—and confronted with industrial unrest, divisions in the labour movement, and his inability to implement Labor’s legislative program, including such matters as a progressive land tax and compulsory acquisition of land for closer settlement—Verran called an election early in 1912 for the Assembly and the Council. Defeat was severe and Verran resigned as Labor leader. In the next Labor Government, in 1915, he was not given a portfolio. He left the Labor Party in 1917 over the conscription issue and, standing as a member of the National‑Liberal Coalition, lost his seat in the election of 1918.[2]

Nevertheless, Verran’s time in the state legislature had lasting legacies. As Premier, Verran introduced the Aborigines Bill (South Australia) in 1910. A well-intentioned piece of legislation, it revealed the ignorance and racism inherent in white attitudes towards Australia’s indigenous people—attitudes Verran himself would demonstrate in full measure as a member of the royal commission on Aborigines (1912–16). Moreover, as a backbencher in wartime South Australia, and supported by the All British League, Verran led the campaign against those of German descent which resulted in the closure of Lutheran schools. He sought to have ‘people of German origin or birth’ disenfranchised and demanded that Lutheran children ‘be taught pure English, and taught by those who are British, and taught what it is to be British’.[3]

In 1921 and 1924, Verran stood as a candidate for Wallaroo, first as an Independent then as a Liberal, but without success. He was also defeated as a Nationalist candidate for the Senate in 1922, and as theNationalist candidate for the House of Representatives seat of Hindmarsh in 1925. During this time, Verran, declared ‘black’ by the union movement, had found it almost impossible to get work.

In August 1927, Verran was chosen to fill the Senate casual vacancy, created by the death of Labor’s Senator McHugh. It was a controversial appointment—the second time in as many years that the Liberal Government in South Australia had used its superior numbers to override precedent. Yet it was an astute move. Verran was an experienced politician and an ardent advocate of states’ rights. ‘I never have been a federalist’, he would announce to the Senate, ‘indeed, I fought against federation, because, in my opinion, federation means the damnation of any country’. The Liberals also used Verran’s nomination to embarrass the Labor Party. The nomination was, according to South Australian Premier, R. L. Butler, ‘an emphatic protest against the attitude of the trade union system in preventing a man from earning a living’. Not surprisingly, for one who saw himself as having ‘a strong personality and a lively individuality’, Verran, once in the Senate, looked forward to the time ‘when parties will disappear and Parliament will consist of men who are at liberty to vote according to their individual opinions’, and asserted: ‘I have never felt so free in my life as I do to-day’.[4]

As a Senator, Verran had most to say on industrial and financial matters. His views on workers and unions had been shaped by his experience as a miner at Moonta and eighteen years as president of the Amalgamated Miners Association (1895–1913). Equating higher wages with greater production costs and favouring ‘revelation’ to ‘revolution’, he opposed the more aggressive tactics of modern union leaders. He had urged the adoption of a sliding scale for miners’ wages rather than a standard wage that industry could not afford to pay. The closing of the copper mines of Moonta in 1923 had convinced him that with the sliding scale the mines could have operated for a further five years.

As industrial relations became more volatile in the late 1920s, Verran recalled the simpler methods of earlier days in Methodist Moonta: ‘If [workers] prayed as much as they swore we should not have any industrial trouble’. In debate on the Conciliation and Arbitration Bill, he argued that union agitators were ‘responsible for much of our present troubles’. Indeed, he made it clear how far he had moved from the more militant sections of the labour movement when he referred to unions as ‘infernal political fighting machines’. During debate on waterfront problems in 1927, he supported the use of the secret ballot in deciding strikes, even going so far as to urge the involvement of wives in such ballots: ‘I have always advocated that before a strike is declared mother should have a voice in deciding if father should strike’. It was his opinion that ‘the judgment of a woman is superior to that of a man’.[5]

On the Financial Agreement Bill of 1927, which was designed to reorganise financial relations between the states and the Commonwealth, Verran was a reluctant supporter of the Nationalist‑Country Party Government. The premiers, he believed, had had no alternative but to sign the agreement. Self-styled as neither a ‘unificationist’ nor a ‘federalist’, he wanted a continuation of the per capita payment which would increase with the rise in Commonwealth revenue or with the growth of population. He proposed voting against the Bill. However, as Verran himself recognised, the complexity of the problem demanded a greater command of the detail than he could give. At seventy-one, he was impatient with detail, preferring to rely on the plain speech of the Cornishman and the Biblical allusions of the local preacher, the latter now becoming repetitive. He voted neither against the Bill, nor for Labor amendments which would have granted some of what he wanted. Now that Federation was established, Verran acknowledged that it was his ‘duty to co-operate and endeavour to make it a success’.[6]

After only a brief career as a senator, Verran was defeated at the 1928 election by Labor’s John Daly. He died on 7 June 1932 at his daughter’s home at Unley, in Adelaide. Following a state funeral, he was buried at Moonta, where his political and religious ideas had been forged. On 21 February 1880, at the residence of Frederick Garland at Moonta, he had married Catherine Trembath, who predeceased him in 1914. Of the eight children of the marriage, seven survived him. One son, John Stanley Verran, followed his father into politics in 1918, as Labor Member for Port Adelaide—in the same election in which Verran failed as a Nationalist for the seat of Wallaroo.

Verran was widely respected as a politician in South Australia, first as Labor member and Premier, later as a member of the National Party, of which he was president in 1922. The Australian Worker commented that with ‘many fine deeds on the credit side of his public ledger’, he would be forgiven for his ‘defection’. Active in the Methodist Church and Freemasonry, Verran had also been Chief Ruler in the Rechabite Lodge. He was proud of his British birth and, although he had been an infant immigrant, continued into old age to assert Britishness as part of his creed: ‘I believe in the British Empire. I have lived under the British flag all my life. I believe in Old England, just as I believe in God’. His daughter, Ruby Horton, recalled Verran as a man who had ‘never sought wealth’, who had ‘died a poor politician but rich in his beliefs’.[7]

[1] Advertiser (Adelaide), 8 June 1932, p. 9; H. T. Burgess (ed.), The Cyclopedia of South Australia, vol. 1, 1907, Cyclopedia Company, Adelaide, p. 220; Oswald Pryor, Australia’s Little Cornwall, Rigby, Adelaide, 1962, pp. 126–129; Arnold D. Hunt, ‘Verran, John’, ADB, vol. 12; Graham Jenkin, Conquest of the Ngarrindjeri, Rigby, Adelaide, 1979, pp. 288–289; Westralian Worker (Kalgoorlie), 2 June 1911, p. 1.

[2] D. J. Murphy (ed.) Labour in Politics: The State Labor Parties in Australia 1880–1920, UQP, St Lucia, Qld, 1975, pp. 263–266, 268; Gordon D. Combe, Responsible Government in South Australia, Government Printer, Adelaide, 1957, pp. 144–146, 202; SAPD, 5 July 1910, pp. 18–27.

[3] SAPD, 18 August 1910, p. 346, 28 September 1910, pp. 617–622; SAPP, Reports of the royal commission on the Aborigines, 1913and 1916; Jenkin, Conquest of the Ngarrindjeri, pp. 244–247, 258–260, 269–270; SAPD, 5 October 1915, p. 1140, 8 August 1916, p. 634, 30 August 1916, pp. 1092–1097, 13 September 1916, p. 1233, 26 September 1917, p. 341, 31 October 1917, pp. 927–930; Elizabeth Haydon Kwan, Which Flag? Which Country? An Australian Dilemma, 1901–1951, PhD thesis, ANU, 1995, pp. 235–236, 243–245, 252–255.

[4] CPD, 12 June 1928, p. 5869; SAPD, 28 July 1927, p. 177; CPD, 28 March 1928, p. 4204; SAPD, 30 August 1927, p. 4; CPD, 12 June 1928, p. 5869, 6 September 1928, p. 6428.

[5] CPD, l2 June 1928, pp. 5866–5869, 6 September 1928, pp. 6429, 6430, l2 June 1928, pp. 5866–5867, 1 December 1927, p. 2350.

[6] CPD, 28 March 1928, pp. 4204–4205; Senate, Journals, 23 March 1928, 28 March 1928; CPD, 6 September 1928, p. 6427.

[7] Advertiser (Adelaide), 8 June 1932, p. 9; Percival Serle, ‘Verran, John’, Dictionary of Australian Biography, vol. 2, A & R, Sydney, 1949, p. 447; Australian Worker (Sydney), 22 June 1932, p. 1; CPD, 12 June 1928, p. 5869; Advertiser (Adelaide), 16 June 1984, p. 2.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 211-214.