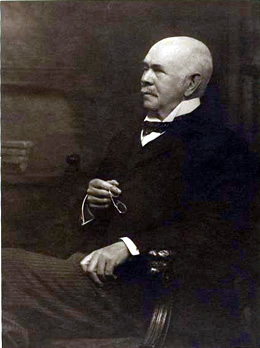

SYMON, Sir Josiah Henry (1846–1934)

Senator for South Australia, 1901–13 (Free Trade; Anti-Socialist Party)

Josiah Henry Symon was born at Wick, Caithness, Scotland, on 27 September 1846, the son of James, a cabinetmaker, and Elizabeth, née Sutherland. Josiah was educated at the Allan’s School, Stirling, the Stirling High School and then inEdinburgh for two years. In 1866, Symon migrated to South Australia and began a legal career, taking articles with his cousin, J. D. Sutherland, at rural Mount Gambier. His fortunes improved in 1870 when a well-prepared brief for leading counsel, Samuel James Way, led to the invitation to transfer his articles to the Adelaide firm of Way and Brook. There he developed a friendship with a fellow clerk, Charles Cameron Kingston, later premier of South Australia, federal father and first Commonwealth Minister for Trade and Customs.

Called to the Bar in November 1871, Symon became a partner with Way and Brook in 1873, and senior partner in 1876 when Way was appointed Chief Justice of South Australia. He took silk in 1881 and refused appointment to the Supreme Court Bench in 1884. As an acknowledged leader of the South AustralianBar for more than thirty years,Symon was said to have towered above his legal and political contemporaries. His grasp of legal principles, his ability to marshal clear and incisive arguments, to break down a hostile witness or to lead the bench or jury to the conclusion he wanted made him the most sought after counsel in Adelaide for major civil and criminal cases. Symon was president of the South Australian Law Society (1898–1903, 1905–19) and a member of the Society of Comparative Legislation and International Law, to whose journal he occasionally contributed.[1]

He was appointed Attorney-General in the short-lived ministry of William Morgan in March 1881, following ‘urgent solicitations’ from the Premier himself. He then sought entry to the Parliament by standing for the electorate of Sturt, which he held from April 1881 until April 1887 when he attempted to transfer to the electoral district of Victoria. He was defeated because of his opposition to protection and to the payment of members. A year earlier, on a visit to England, he had declined nomination for a safe Conservative seat in the House of Commons believing that his life and work lay entirely in his adopted homeland. While a member of the colonial Parliament, his main areas of interest were free trade and the independence of the judiciary. He twice (1882 and 1884) introduced an Abolition of Oaths Bill to promote a system of ‘truthfulness in courts of justice’.[2]

Symon was an enthusiast for Federation, although he opposed the Federal Council Bill when it came before the South Australian Parliament in 1884 on the grounds that the Federal Council was not accountable to the colonial parliaments. Despite the fact that he was not Australian-born, in 1894 the Australian Natives’ Association (ANA) invited Symon to become president of the South Australian branch of the Australasian Federation League. The ANA established the League to overcome the notion that the ANA itself was thought too unrepresentative to lead the federal movement.

It was a good choice. Symon, often peppery, if not arrogant, in his dealings with his contemporaries, was widely regarded as one of the finest orators of his day, particularly in the public domain. In Adelaide, in 1897, he was chosen at the request of the Chamber of Manufactures, of which he was at some time a member,to give an official oration for Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee in the Town Hall. Symon held his large audience spellbound for two hours with a speech entitled, ‘Tis Sixty Years Since’. During the federation campaign, he packed the Adelaide Democratic Club for a speech on the abolition of appeals to the Privy Council. His fine physical presence, his dignified bearing, his clear and resonant voice, his incisive arguments, as well as the manipulation of the emotions of his audience, all told in his favour.[3]

In 1896, Symon stood for election to the 1897–98 Australasian Federal Convention (1897–98) as a South Australian delegate. ‘Why stand shivering on the brink?’ he asked his audience in a rousing campaign speech at the Adelaide Town Hall. He spoke in support of a powerful and representative Senate and the establishment of a High Court free of appeals to the Privy Council. He pleaded for unity from the six colonies: ‘A six-inch pipe carries a greater volume than six of one inch’. Then he added: ‘By federating we shall become a nation—we are not one now. We shall form a national character based upon a lofty ideal that does not now exist’.[4]

Duly elected, at the Convention Symon proved himself one of the ablest men present and won the respect and trust of many whose political opinions were very different from his own. Fiercely independent in character, he insisted on putting party issues aside and on making the national interest pre-eminent. He was adamant that while protecting the proper interests of the federating colonies, the ultimate dominance of the House of Representatives over the Senate should prevail in order to protect responsible government. But he also held that the Senate had to be ‘a check . . . upon the representative chamber’.[5]

Commenting on the convention delegates of 1897, Alfred Deakin considered that Symon ‘retained more of the traditions of the court than of the legislature’. Certainly, as chairman of the Convention’s judiciary committee, Symon’s major contribution was his meticulous redrafting of the judiciary measures of Samuel Walker Griffith’s draft Constitution of 1891, a matter which appears to have been the cause of some annoyance to Sir Samuel. Throughout the Convention, Symon maintained his view that the Privy Council was an anachronism. In the face of opposition from the ANA, division within the Federation League, and lobbying from British and Australian mercantile interests, he argued that the Privy Council was not relevant to a federated Australia where the High Court should be ‘final Court of Appeal’. While Symon was not one of the delegates who finally carried the Constitution Bill to London, from Adelaide he watched the Privy Council issue carefully. Telegrams between Symon and his erstwhile friend and foe, Kingston, flew back and forth to London in a vain attemptto prevent the British Government watering down the clause which had been the cause of so much debate. The issue led to an attack on Symon in The Times, and brought him into conflict withhis former mentor, Sir Samuel Way, and the then Chief Justice of Queensland, Sir Samuel Griffith.[6]

Prior to the holding of the federal plebiscite in Western Australia in 1899, Symon, encouraged by Deakin, visited Kalgoorlie and Coolgardie in an effort to win the support of the crucial goldfields area. In a stirring address at the Miners’ Institute in Kalgoorlie, speaking as a ‘t’othersider’,Symon said that Federation was ‘simply the knitting together of the people of Australia as one nation’, which at the same time, preserved ‘the identity of each separate colony as a separate State’. (He would never shift from his belief in all colonies/states belonging to the Federation, later referring to the Western Australian secession movement as a ‘wicked will of the wisp used by thoughtless or misguided men’.) In 1900, Symon published in the Yale Review a history of the Australian federal movement and, on 1 January 1901, was created KCMG for his eminent services to the cause of Federation.[7]

Symon stood for the Senate as a Free Trader at the first federal election in 1901, and as an Anti-Socialist in 1906, on both occasions topping the Senate poll in South Australia. While his lucrative law practice made constant attendance difficult, his contribution to debate was of a high order. If his principal concern was to refine the quality of legislation rather than engage in controversial policy issues, Symon was also anxious to articulate the Senate’s role. This he did in May 1901, arguing that the Senate was ‘constituted peculiarly and specially to be the guardian of the rights of the States’, and that it was ‘a House of review and revision’.

As a president of the South Australian Free Trade League and an honorary member of the Cobden Club, it fell to Symon, in the first Parliament, to marshal the Free Trade forces in the Senate. As a result, Symon was first Leader of the Opposition in the Senate (albeit an unofficial one) from 1901 to August 1904, and again from July 1905 until he resigned in November 1907. As Government Leader during the Reid–McLean Ministry (August 1904 to July 1905), he piloted the Conciliation and Arbitration Bill through the Senate. During debate on the Customs Tariff Bill of 1902, Symon spoke frequently, especially during the thirty-three days the Senate sat in committee on this complicated and divisive legislation. No amendment could be moved by the Free Trade Party in the Senate unless agreed to by a majority of the Party, or approved by Symon himself. Symon also had the power to decide who should move amendments. Respected and perhaps even feared as leader, he expected his Free Trade colleagues to abide by ‘caucus’ meetings. Senator Best remarked of Symon that while the ‘learned Senator’ claimed ‘sweet reasonableness’, he had ‘war . . . in his heart’. Amongst those with whom Symon came into conflict, was Senator Neild, who castigated the Free Trade Party for ‘transcending even the “cast iron pledge” of the Labour Party’.[8]

Symon himself, however, remained clearly uncomfortable about the evolving party system. On resigning as Leader of the Opposition in the Senate, he wrote to Senator Edward Millen: ‘I am free and feel it’. In 1903, he had expressed some relief that the Judiciary Act was ‘above party’. Speaking on the Copyright Bill in 1905, he commented that it was ‘always refreshing to get a Bill which rises above and is outside the stormy limits of party politics’. Nonetheless, despite earlier lobbying by the suffragist, Catherine Helen Spence, he strongly attacked the proportional representation clauses in the Commonwealth Electoral Bill of 1902, affirming that ‘single-issue’ groups would divide the major parties.[9]

Perhaps his greatest strength was his vigilance in upholding the Constitution. He sought to guide senators who had not been members of the Australasian Federal Convention and to imbue them with his own high idealism and national sentiment. Speaking on the Post and Telegraph Bill in 1901, he said: ‘Uniformity is the essence of the Constitution under which we are proceeding, and if we are to legislate upon this matter at all, undoubtedly it ought to be in such a way as not to discriminate between the different States in regard to legislation that is intended to be for the benefit of the people of the Commonwealth’.

When the Senate, during debate on the Customs Tariff Bill in 1902, first pressed a request for an amendment under section 53 of the Constitution, Symon held that there was no constitutional limitation on the number of times the Senate could repeat its requests to the House of Representatives.Referring, as he often did, to the convention debates, he said the delegates had ‘not intended . . . that the sending of requests should be limited to one occasion’. He was adamant that the House of Representatives should give reasons for its refusal to amend. On this issue, he was anxious to keep the President of the Senate, Sir Richard Baker ‘on the rails’, as indeed he endeavoured to do during debate on the Sugar Bonus Bill in 1903. In what Professor Geoffrey Sawer described as a ‘masterly’ speech, Symon declared that it was a ‘matter of supreme indifference’ to him what happened to the Bill itself. The real issue, Symon insisted, was the constitutional point as to whether or not the Senate had the power to amend legislation such as the Sugar Bonus Bill, which may increase expenditure or taxation. In this, he questioned the validity of Baker’s case (that the Senate could amend outright) and cautioned that until the Senate had considered the matter further, a request to amend should be sent to the House, not an amendment.[10]

For Symon, the key ‘nation building’ legislation in the first Parliament was the Judiciary Act, which created the High Court of Australia—a body which he would have preferred to see established directly by the Constitution because of its crucial importance to the federal system. Earlier, Symon had opposed those who, for economic reasons, wanted to create a Court of States’ Chief Justices, arguing that the Court’s constitutional basis required that it not be founded upon inappropriate bias toward the states. As Attorney-General in the Reid–McLean Ministry (1904–05), he disputed the opinion of Sir Samuel Griffith, the first Chief Justice of the High Court, that the Court should be peripatetic. Symon argued that, in accordance with the Constitution, the Court, whose members should ‘breathe the very atmosphere of this Constitution’, should be at the seat of government (then in Melbourne). He claimed that the High Court had been ‘set afloat practically without a rudder’, and in keeping with his view on responsible government added that the ‘administration of justice and the places at which sittings of the Court shall take place are matters for the Executive’. He argued for an early decision on the federal capital site because of New South Wales’ rights under section 125 of the Constitution (that the seat of Government ‘be in the State of New South Wales’).In 1907, as chairman of the committee of disputed returns and qualifications that inquired into Joseph Vardon’s petition over the filling of South Australia’s third Senate seat, he drafted the Committee’s well-considered report.[11]

The streak of independence that had been so marked throughout his political career prevented him, in 1909, from joining the fusion of the three non-labour groups, his anti-fusion speech in the Senate including a stinging attack on Deakin. In 1912, Symon made it clear that, while he was prepared to accept nomination for the 1913 federal election, he would not sign the Liberal Union pledge, as this would have necessitated his agreement that if not selected he would retire from politics. As a result, the Liberal Union refused to endorse him for the 1913 election. He stood as an Independent and was defeated. So closed a useful, if not outstanding, career in the Senate.

It was probably time for him to go: his attendance had been declining and, by the end of his term, he was speaking but rarely. He continued to work in the courts until 1923 and in chambers almost until his death. In 1928, in evidence to the royal commission on the Constitution, he referred to a unitary form of government as, not an amendment to the Constitution, but a ‘revolution’. The independence of the judiciary was still an important principle to him when, in 1931, he opposed the appointment of Sir Isaac Isaacs as Governor-General.[12]

Symon was a man of broad scholarship and frequently lectured on literary subjects. In 1929, he wrote Shakespeare the Englishman. He was president of the South Australian Literary Societies’ Union, and in 1898 appointed ‘Governor’ of its model Parliament. He was a patron of the Poetry Recital Society and the Home Reading Union. His personal library grew to encompass some 10 000 volumes, mainly on law, politics, literature, history and biography. The legal works he bequeathed to the University of Adelaide, the general material to the South Australian Public Library. An active member of the parliamentary library committee throughout his years in the Senate, Symon was thought by his colleagues to have made a distinguished contribution to the library’s establishment. In 1905, speaking on the Copyright Bill, he commented: ‘We cannot possibly have a supply of good books unless men of letters are liberally remunerated . . .’.

During World War I, Symon campaigned for the war effort and became vice-president of the Royal Empire Society and of the Anglo-Saxon Club. He was a member of the Council of the University of Adelaide for many years and hoped to establish there a women’s college. Thwarted in that, he built a Women’s Union insisting it be managed only by university women. His philanthropy extended in many directions, though perhaps none was more significant than his support, personal as well as financial, for the Minda Home for intellectually handicapped children, for this spoke of a sorrow in his own life.

On 8 December 1881, at St Peter’s Cathedral, Adelaide, Symon had married Mary Eleanor Cowle, daughter of C. T. Cowle of North Adelaide. There were ten children of the marriage, five sons and five daughters, all of whom, with their mother, survived their father. The family lived comfortably at Upper Sturt, where Symon enjoyed the farming pursuits of a gentleman, also owning the Auldana vineyard. He died at North Adelaide on 29 March 1934 and was given a state funeral in honour of his many contributions to the Australian nation. George Pearce was not alone amongst those of Symon’s contemporaries who considered that he should have gone to the High Court—but this ‘contribution’ had been denied him.[13]

[1] H. T. Burgess (ed.), The Cyclopedia of South Australia, vol. 1, 1907, Cyclopedia Company, Adelaide, pp. 176–177; J. J. Pascoe (ed.), History of Adelaide and Vicinity, Hussey & Gillingham, Adelaide, 1901, pp. 371–374; Sydney Mail, 9 April 1913, p. 8.

[2] Symon Papers, MS 1736/6/17a and 17b, NLA; Don Wright, ‘Symon, Sir Josiah Henry’, ADB, vol. 12; Pascoe, History of Adelaide and Vicinity, p. 373; SAPD, 27 August 1884, pp. 777–784.

[3] For a detailed account of this phase of Symon’s career see D. I. Wright, ‘Sir Josiah Symon, Federation and the High Court’, Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol. 64, September 1978, pp. 73–88; SAPD, 28 August 1884, pp. 800–805; Symon Papers, MS 1736/4/6, NLA; Herald (Adelaide), 28 April 1900, p. 8.

[4] Wright, ‘Symon, Sir Josiah’, ADB; South Australian Register (Adelaide), 17 February 1897 (supp.).

[5] Sir Josiah Symon, ‘The Dawn of Federation: Some Episodes, Letters and Personalities and a Vindication’ (edited and annotated by D. I. Wright), South Australiana, vol. 15, September 1976, pp. 113–151; CPD, 16 October 1912, p. 4267; AFCD, 10 September 1897, p. 299.

[6] Alfred Deakin, ‘And Be One People’: Alfred Deakin’s Federal Story, with an introduction by Stuart Macintyre, MUP, Carlton South, Vic., 1995, p. 61; J. A. La Nauze, The Making of the Australian Constitution, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1972, pp. 130, 132; AFCD, 20 April 1897, pp. 984–985, 11 March 1898, pp. 2296–2309, 2324–2341; L. F. Crisp, Australian National Government, Longman Cheshire, Melbourne, 1978, pp. 29–31; John Quick and Robert Garran, The Annotated Constitution of the Australian Commonwealth, A & R, Sydney, 1901, pp. 748–750; Margaret Glass, Charles Cameron Kingston: Federation Father, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1997, pp. 94–97, 175–200; For an account of the Privy Council issue, see Anne Twomey, The Constitution: 19th Century Colonial Office Document or a People’s Constitution?, Background Paper 15/1994, Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 1994, pp. 19, 27.

[7] Letter, Alfred Deakin to Symon, 9 June 1898, Symon Papers, MS 1736/9/100, NLA; Kalgoorlie Miner, 4 April 1899, p. 2; Coolgardie Miner, 4 April 1899, p. 6; Telegram, Symon to Senator George Pearce, 7 March 1933, Pearce Papers, MS 213/16/309, NLA; J. H. Symon, ‘United Australia’, Yale Review, vol. 9, August 1900, pp. 129–163.

[8] CPD, 23 May 1901, p. 230; J. H. Symon, ‘Why I am a Free Trader’, leaflet no. 127, Cobden Club, London, 1901; Letters, Senator J. T. Walker to Symon, 11 June 1901 and Symon to Senator J. S. Clemons, 12 September 1905, Symon Papers MS 1736/10/101 and 415, NLA; Gavin Souter, Acts of Parliament, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1988, p. 70; P. Loveday, A. W. Martin & R. S. Parker (eds), The Emergence of the Australian Party System, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1977, pp. 409–410; CPD, 1 May 1902, p. 12180; Letter, Senator J. C. Neild to Symon, 8 May 1902, Symon Papers, MS 1736/10/152–153, NLA.

[9] Letter, Symon to Senator E. D. Millen, 30 November 1907, Symon Papers, MS 1736/10/553–554; CPD, 31 July 1903, pp. 2920–2946, 30 August 1905, p. 1634; Correspondence between Catherine Spence and Symon, MS 1736/6/18, 19 and 1736/1/885, Symon Papers, NLA; G. S. Reid and Martyn Forrest, Australia’s Commonwealth Parliament 1901–1988, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1989, p. 103; CPD, 27 February 1902, p. 10420.

[10] CPD, 27 June 1901, p. 1710; Reid and Forrest, Australia’s Commonwealth Parliament, p. 212; CPD, 9 September 1902, pp. 15824–15825; Symon Papers, MS 1736/10/190–193; Geoffrey Sawer, Australian Federal Politics and Law 1901–1929, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1956, p. 31; CPD, 22 July 1903, pp. 2382–2385.

[11] Crisp, Australian National Government, p. 60; Souter, Acts of Parliament, pp. 94–95; CPD, 23 May 1901, p. 234, 28 November 1905, pp. 5835–5839, 5844, 7 February 1902, p. 9817; Sawer, Australian Federal Politics and Law 1901–1929, p. 81; CPP, Report of the committee of disputed returns and qualifications upon the petition of Joseph Vardon, 1907.

[12] CPD, 7 July 1909, pp. 878–896; Loveday et al., The Emergence of the Australian Party System, p. 292; Correspondence and papers between Symon and Joseph Vardon et al., MS 1736/12/41–50, 87–89, 91–96; CPP, Report of the royal commission on the Constitution, minutes of evidence, part 4, pp. 1082–1087; Sir Josiah Symon, Governor-Generalship of Australia: Appointment of Sir Isaac Isaacs, Adelaide, 1931.

[13] The Literary Societies’ Journal, 18 July 1904, pp. 4–7; Geoffrey A. J. Farmer, ‘Sir Josiah Symon’s Library in the Public Library of South Australia’, Australian Library Journal, vol. 10, April 1961, pp. 57–61; CPD, 30 August 1905, p. 1636; Chronicle (Adelaide), 30 March 1929, p. 52; Averil G. Holt, The Vanishing Sands, City of Brighton, SA, 1991, pp. 170–171; Adelaide Observer, 7 February 1903, p. 24; Advertiser (Adelaide), 30 March 1934, pp. 7–8; CPD, 28 June 1934, pp. 4–5, 17–18; George Pearce, Carpenter to Cabinet: Thirty–Seven Years of Parliament, Hutchinson & Co., London, 1951, p. 48.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 162-167.