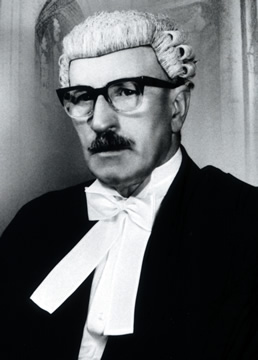

LOOF, Rupert Harry Colin (1900–2003)

Clerk of the Senate, 1955–65

Rupert Loof, the seventh Clerk of the Senate, became best known for his longevity, as he lived to the age of 102 years, and his time in retirement (thirty-eight years) was almost as long as his service to the Senate (thirty-nine years). Fortunately, he was a man of many interests and remained intellectually sharp to the very end of his life. Unfortunately, his fame in being so long-lived tended to overshadow his very productive time as Clerk.

Rupert Harry Colin Loof was born at Katamatite, Victoria, on 15 August 1900, the son of Charles Loof, a farmer, and his wife Mary Ann, née Robins. He was educated at state schools in Katamatite and in the Melbourne suburb of North Carlton, before attending Melbourne High School. He also studied at a Melbourne business academy where he learnt shorthand and typing. On 1 February 1919 he entered the Commonwealth Public Service in Melbourne as a ‘naval staff clerk’ in the Department of the Navy. After some other positions and nine months as personal clerk to the First Naval Member, Commonwealth Naval Board, on 21 October 1926 he transferred to the Senate as a clerk and shorthand writer.[1]

At the time of his appointment, the Commonwealth Parliament was still meeting in Melbourne, but in early May 1927 he was among forty parliamentary officers camping in the new Parliament House in Canberra before its official opening by the Duke of York (later King George VI) on 9 May 1927. Loof arrived in Canberra after a three-day motorbike journey from Melbourne, which included riding through rivers.

Loof served as clerk and shorthand writer (1926–c. 1929), correspondence and reading clerk (c. 1929–30) and clerk of the records and papers from around 1930 until his appointment as Usher of the Black Rod and Clerk of Committees on 1 January 1939. He held this position until 30 November 1942, by which time he had been awarded a Bachelor of Commerce degree from the University of Melbourne. The ceremonial and administrative position of Usher of the Black Rod carried with it in Loof’s time the secretaryship of Senate committees, including the Regulations and Ordinances Committee, and he assisted a select committee which investigated the discharge of Captain T. P. Conway from the Australian Army.

From December 1942 until July 1955 Loof served as Clerk Assistant (the equivalent of the current position of Deputy Clerk) of the Senate. Between August 1945 and December 1954 he also held the post of secretary of the Joint House Department, which administered building services and catering in Parliament House. He had responsibility for organising all formal functions in Parliament House in connection with the visit of Queen Elizabeth II in 1954, the first visit to Australia of a reigning British monarch. The Queen opened the third session of the twentieth Parliament on 15 February 1954, which event Loof also organised. He was appointed Clerk of the Senate on 21 July 1955.[2]

During the 1930s and 1940s the Australian Parliament was an institution very resistant to change, and continued in well-worn procedural paths, which largely encouraged subservience to the executive government. This no doubt was due in part to the crushing effects of the Great Depression and World War II, but also had to do with Empire loyalty and faithfully following the Westminster pattern. In Loof’s time as Clerk this began to change, and the Senate began to adjust its processes to be in keeping with its constitutional role. Loof had a good understanding of that role and a mind open to ideas and innovation, and played a significant part in this awakening. The introduction of proportional representation for elections to the Senate in the election of 1949 provided a more evenly balanced chamber and the context for this historical shift. Senators became more interested in their part in the legislative process, and perceived the gap between constitutional theory and the reality of their wartime irrelevance. They particularly became interested in committee work and the scrutiny of legislation.

In dealing with the Government’s budget and the annual and additional appropriation bills, the Senate had a general budget debate, largely given over to political and partisan oratory, and then waited for the bills to arrive from the House of Representatives, by which time there was inadequate opportunity to examine the details of expenditure proposals and raise matters of concern about government priorities. The Leader of the Government in the Senate from 1959 to 1964, Senator Sir William Spooner, began to search for a way of dealing more effectively with the bills. It is significant that a Leader of the Government in the Senate sought ways to make the Senate more effective, which inevitably meant making life more difficult for government. This was partly due to pressure from government backbenchers, but it says a great deal about how seriously government senators took their role in those times and the quite different situation today, when governments are expected to use every endeavour to ‘streamline’ parliamentary processes for the benefit of the executive. Loof worked closely with Spooner in developing the new procedures. They involved the content of the appropriation bills, the actual expenditure proposals, being tabled in the Senate as soon as the bills were introduced in the House, and the Senate’s consideration of them at length in committee of the whole, which involved unlimited opportunity for senators to speak and to question Senate ministers about the expenditure and government priorities. It is difficult to exaggerate the radical nature of this proposal, as it involved the Senate effectively considering legislation before it had passed the House of Representatives, an abomination in the sight of Westminster purists. Indeed, the Labor Opposition opposed the changes on that basis, thereby attempting to reject an opportunity offered to them by the government to more effectively hold that government to account. Fortunately, this narrow view did not persist. The new estimates procedure was the beginning of a long train of innovations which enhanced the ability of the Senate to scrutinise government operations.[3]

In 1956 Loof initiated the establishment of an Australian branch of the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU), a kind of parliamentary United Nations involving members of parliaments around the globe. It is difficult now to appreciate that this was a radical step. The Australian Parliament was still seen in some sense as a subordinate legislature under the ‘Imperial Parliament’ at Westminster, and a loyal member of the British Empire, which had become the Commonwealth of Nations. Joining the IPU was a symbolic recognition that the country was an independent jurisdiction with an independent legislature.

During 1963 and 1964 Loof initiated and carried through a reorganisation of the Senate Department, providing it with a senior structure appropriate to its constitutional role and a more satisfactory career path for its senior officers to gain the knowledge, experience and culture vital in supporting the Senate’s enhancement of its performance of that role.

Loof was active in explaining the Senate to the public. Although this was done in a very modest way by current standards, the volume of information published about the operations of the Senate markedly increased during his tenure. He wrote several articles for parliamentary journals, explaining changes in the Senate and how they affected the system of government, and also ventured beyond the exclusive club of parliamentary officers.[4]

In accordance with the legislation then in force, he was compelled to retire in 1965 at age sixty-five, although he was then still extremely youthful physically and mentally. The long-serving President of the Senate, Sir Alister McMullin, who, like his political colleagues, had no compulsory retiring age, paid tribute to his work: ‘In tendering this advice, he has never relied simply on the standard authorities … His inbuilt understanding of the parliamentary machine and its workings has ever been present and the functioning of our parliamentary institution has been paramount in his mind at all times’. Spooner wrote privately to Loof to thank him for ‘the help and assistance’ given over the years during which he was a minister, stating that he had ‘a great respect’ not only for Loof’s ‘knowledge of Senate procedure’ but also for his ‘sagacity and wisdom’.

Like many of his colleagues, Loof had not been enthusiastic about leaving Melbourne for Canberra in 1927, but he came to love the city, choosing to retire there. On 28 December 1929, at the Methodist Church, Canterbury, Victoria, he had married Margaret Beatrice, née White, sister of Harold White (later Sir Harold), Parliamentary Librarian from 1947 to 1967. There were three Loof children. Loof was a man of wide interests. A lover of music (the piano and the pipe organ), within a year of his arrival in Canberra he had formed an orchestra to accompany plays performed at the newly built Albert Hall. Other activities included painting (mainly oils), golf (he designed and produced a golf driving practice device, which was ‘Invention of the Week’ on ABC TV’s The Inventors program in November 1978), pottery (using a kiln and a wheel he made himself), and, in youth and middle age, tennis. He was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire in June 1962.[5]

The reliability of Loof’s memory, even in advanced old age, was demonstrated by a curious piece of information he conveyed to the author. The richly decorated mid-Victorian chamber of the Legislative Council in Melbourne, where the Senate met until 1927, features an array of female figures variously called angels or goddesses and representing such virtues as ingenuity and industry, each one holding a symbol of her attribute. One holds a chain and is supposed to represent unity. Loof’s story was that the chain was originally broken and the figure represented liberty, but maintenance staff carrying out repairs before the building was handed back to the Victorian Parliament by the Commonwealth saw the broken chain and ‘fixed’ it. This story seemed scarcely credible, but photographs taken in the nineteenth century show that the chain was indeed originally broken, so Loof’s account is firmly grounded in fact. For eighty years the Legislative Council has been under the auspices of the wrong goddess, and remains so to this day in spite of the evidence supporting Loof’s story being presented to the Victorian authorities.

Loof was a smallish, dapper man with a courtly manner. His meticulous attention to detail was famous. He combined a scrupulous sense of propriety with a realistic assessment of human nature (particularly as manifest in politicians), and was a shrewd judge of character. He was given to pithy utterances with a biblical flavour (his father was a Methodist lay preacher). His colleagues recall several rather eccentric habits, such as writing reminder notes to himself and placing them in his upturned hat.

To mark his 100th birthday, Loof was invited to a special function in the President’s suite at Old Parliament House, attended by the President and the Clerk, at which he impressed all present with his mental acuity. The President mentioned the occasion in the Senate.

Loof died on 21 March 2003, and again the President referred to the occasion in the Senate. By that time senators and staff who had served with the venerable Clerk were long gone, and most of those present were not acquainted with him, but the President sombrely observed: ‘I thought that the Senate should note his passing’.[6]

[1]Clerks

Loof, Rupert Harry Colin

This entry draws upon an earlier biography by Derek Drinkwater, who interviewed Rupert Loof in 1995: ‘Rupert Loof: Clerk of the Senate and Man of Many Parts’, Papers on Parliament, Department of the Senate, no. 28, Nov. 1996, pp. 105–12. The recollections of the author and colleagues have also been employed; Loof, Rupert Harry Colin, Department of the Senate personal history file, A8804/22, box C1, NAA.

[2] Bulletin (Syd.), 6 May 1997, p. 29; CT, 15 Aug. 2001, p. 1.

[3] CPD, 26 Sept. 1961, pp. 641–53, 27 Sept. 1961, pp. 654–5, 681.

[4] G. S. Reid and Martyn Forrest, Australia’s Commonwealth Parliament 1901–1988: Ten Perspectives, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1989, pp. 416–18; R. H. C. Loof, ‘The Legislative Process in the Senate’, Public Administration, June 1964, pp. 146–58.

[5] CPD, 26 May 1965, p. 1293; Letter, W. Spooner to R. H. C. Loof, 5 July 1965, provided by Rupert Loof to Derek Drinkwater in 1995; CT, 13 Aug. 1965, p. 3; Peter Freeman Pty Ltd Conservation Architects and Planners, ‘The Albert Hall Precinct Canberra: Conservation Management & Landscape Plan’, 27 Apr. 2007, ACT Department of Territory and Municipal Services, viewed 17 Apr. 2009, <http://www.tams.act.gov.au/>.

[6] CT, 1 Apr. 2003, p. 9; CPD, 15 Aug. 2000, p. 16331, 24 Mar. 2003, p. 9933; CT, 28 Mar. 2003, p. 13.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 3, 1962-1983, University of New South Wales Press Ltd, Sydney, 2010, pp. 553-557.