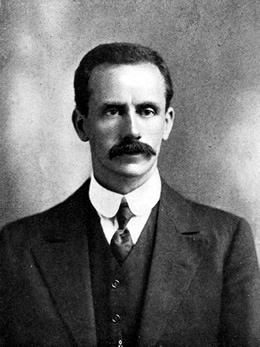

WATSON, David (1870–1924)

Senator for New South Wales, 1914–17 (Labor Party)

David Watson’s Baptist upbringing in a Scottish mining town, may well account for his work as miner, union official and temperance activist, and for his refusal in Parliament to exchange principle for political expediency. Watson was born on 14 February 1870 at Shawfield, Rutherglen, Scotland, the son of John, a miner, and Jane, née Marshall. The young David was working by the age of twelve and when the family migrated to Australia in 1884 became a miner in Newcastle, the district with which he was thereafter associated. A miner for some twenty-five years (with a break in the early 1900s when he worked for the Baptist Ministry’s Home Mission), Watson was committed to the improvement of conditions in the mines. In 1910, he was elected to the presidency of the Colliery Employees’ Federation, defeating the militant Peter Bowling. Watson was among those who were instrumental in having the hated afternoon shift in the coalmines of northern New South Wales abolished.He had earlier joined the Wallsend branch of the Political Labor League. These dual activities were to come into conflict during his career.[1]

Watson stood unsuccessfully for the Senate in 1913, but was a member of the strong group of Labor senators elected in New South Wales after the double dissolution of 1914. His position at the polls resulted in his being a short-term senator, and he was again a candidate at the 1917 election. By then he had taken a conciliatory position in the conflict between the Holman Government and the emerging industrial movement which erupted at the New South Wales Labor conference of 1916 and this probably did not assist his chances of re-election. Though preselected, he was ranked third behind Bowling and Senator Arthur Rae. Watson outpolled both his Labor colleagues, due perhaps to his having become (see below) a somewhat controversial senator, though, in the event, none of the Labor team for the Senate was elected.

Entering the Senate at the outbreak of World War I, he declared in his first speech his allegiance to the British Empire. As a temperance activist, Watson favoured liquor-free or so-called dry canteens within Australian ‘military encampments’, arguing that nothing contributed more to ‘the physical welfare and moral well-being of our soldiers’. He kept a sharp eye on employment levels in the coal industry, imploring the Commonwealth Government to provide alternative employment or unemployment relief to miners forced from their jobs by the major decline in coal exports caused by the war. Convinced that ‘the strength and the stability of a country depend upon its workpeople’, he was a staunch supporter of social welfare initiatives, including widows’ and orphans’ pensions. ‘There can be nothing more degrading’, he said, ‘or demoralizing to our civilization than the necessity for women who have been bereft of their breadwinners to leave their children to stray about the streets . . .’.[2]

Watson’s term in the Senate was little noticed until its end, in part, because, as he said: ‘unless I feel that I have a subject on which I can speak, I am practically a silent man in conversation’. Still, he did speak with effect on industrial matters, and with other Labor members took a consistent stand against conscription. The pain for him on that issue was considerable: he had two sons at the front and was strongly in favour of voluntary recruitment. He objected to the idea of ‘the conscript slave . . . coerced into action against his own free will’. His unpopular stand at the state Labor conference and active association with the temperance movement placed him at odds with some sections of his party. Of his industrial credentials and sincerity there could be no doubt, but after the conscription split, if a Labor senator were to be targeted by the Hughes Nationalist Government, then Watson was the man.

On 2 March 1917,Watson made a statement to the Senate in which he alleged that the Prime Minister, W. M. Hughes, had attempted to bribe him to join the pro-conscriptionist camp, suggesting also that the President of the Senate, Thomas Givens may have been involved in the affair. Hughes sued for libel, but parliamentary privilege shielded Watson, who vehemently maintained the truth of his charges against Hughes. On 13 March 1917, the Senate passed a motion that a royal commission should investigate the matter, but the election that year intervened and the issue died after Watson failed to be re-elected.[3]

After his defeat, Watson returned to his temperance work. A member of the Good Templars and of the Independent Order of Rechabites, he lectured for the New South Wales Prohibition Alliance, working also for another temperance body, the Queensland Strength of Empire Movement, and assisting in the organisation of the prohibition movement in Victoria. In March 1922, he stood unsuccessfully for the state seat of Newcastle. During the campaign, his statements on prohibition were held to be inconsistent with Labor Party policy. He withdrew from the signing of the temperance Modern Pledge, though not from his support of prohibition.[4]

Approximately two years before his death, Watson had moved to Sydney. He died in Lewisham Hospital on 4 December 1924 and was buried in the Baptist section of Newcastle’s Sandgate Cemetery. In 1894, he had married Drucilla, née Dennett. His wife and Henry, David and Arthur, three of his four sons, survived him. Earlier that year, the New South Wales Rechabite and Temperance Magazine had written:

His rugged Scotch accent has charmed a thousand audiences. In the bush township and the cities he has won a way to the front rank of publicists . . . It is well known and often remarked, that Parliamentary experience spoils men. Such cannot be said of David Watson. He took into Parliament with him a native honesty of purpose, and his years of experience in the Senate did not lessen his enthusiasm for those things which had formed so large a part of his life before he became a Parliamentarian.[5]

[1] Jennifer Sloggett, Temperance and Class: with Particular Reference to Newcastle and the South Maitland Coalfields, 1860–1928, MA thesis, University of Newcastle, 1989, pp. 342–343; Information from Jennifer Sloggett; New South Wales Rechabite and Temperance Magazine (Sydney), 15 February 1924, p. 13; Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, 6 December 1924, p. 5, 9 December 1924, p. 5, 11 July 1914, p. 4, 30 December 1912, p. 5; Edgar Ross, A History of the Miners’ Federation of Australia, Australasian Coal and Shale Employees’ Federation, [Sydney] 1970, pp. 191–192.

[2] CPD, 8 October 1914, pp. 21–25, 25 November 1914, p. 972, 27 May 1915, pp. 3462–3463, 8 October 1914, p. 22.

[3] CPD, 5 March 1917, p. 10940, 22 September 1916, p. 8912, 8 December 1916, p. 9590, 1 March 1917, pp. 10774–10779, 2 March 1917, pp. 10847–10849, 10890–10891, 10899–10902, 10911–10912, 5 March 1917, pp. 10936–10942, 13 March 1917, pp. 11225–11226, 11270–11271; Argus (Melbourne), 3 March 1917, p. 18; Senate, Journals, 13 March 1917.

[4] Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, 9 December 1924, p. 5; Jennifer Sloggett, MA Thesis, pp. 186–187, 342–349.

[5] Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, 5 December 1924, p. 7; SMH, 6 December 1924, p. 16; New South Wales Rechabite and Temperance Magazine (Sydney), 15 February 1924, p. 13.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 58-60.