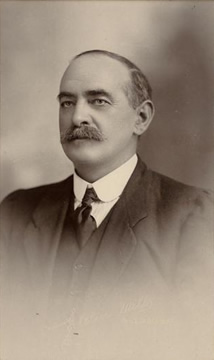

EARLE, John (1865–1932)

Senator for Tasmania, 1917–23 (Nationalist Party)

‘Amid all the confusion of voices’, wrote Punch in 1917, referring to John Earle’s move to the Senate to join the government of W. M. Hughes, ‘no more bland expression could have been imagined than that of Senator Earle when he asked to be informed what all the fuss was about’. John Earle, blacksmith and miner, was born at Bridgewater, Tasmania, on 15 November 1865. He was the son of Charles Staples Earle, a farmer of Cornish descent whose grandfather had been an early settler of the district, and his wife Ann Teresa, née McShane. Ann’s Roman Catholicism does not appear to have been a formative influence in her son’s life. John was educated at Bridgewater State School and as a boy helped his father on the farm. In 1882, he was apprenticed to Kennedy’s foundry in Hobart as a blacksmith and enrolled in engineering and science classes at the Hobart Technical School.

An interest in politics developed from attendance at lectures at the Hobart Mechanics’ Institute. Membership of the Hobart Debating Club brought him into contact with the Attorney-General, Andrew Inglis Clark, who introduced him to the Tasmanian Political Association and discussions on contemporary political issues, including, no doubt, Federation. His friendship with Hobart City Librarian, A. J. Taylor, enhanced his interest in literature and social subjects.

On completing his indentures, Earle worked on the Mathinna, Zeehan and Corinna goldfields and became an active union organiser. With James Long, he was one of the ‘dangerous agitators’ blacklisted by the manager of the Mt Lyell Company. He was selected to attend a government mining conference in Hobart in 1893 as a miners’ representative. Returning to Zeehan in 1898, he became chairman of the Hospital Board, a member of the Zeehan Municipal Council, and president of the Gormanston branch of the Amalgamated Miners’ Association (AMA). In 1901, Earle chaired a conference in Zeehan which established the Workers’ Political League. In 1903, he was elected president of the first formal labour conference in Hobart. Between 1906 and 1917, he was treasurer almost continuously at the League’s annual conferences, and in 1908 its general secretary.[1]

Earle was elected to the Tasmanian House of Assembly as Labor member for Waratah in March 1906 (having been narrowly defeated in 1903) and as Member for Franklin from April 1909 to March 1917. In April 1906, he became the first leader of the Parliamentary Labor Party in Tasmania, going on to be Leader of the Opposition (June 1909–April 1914) with a brief interlude (20–27 October 1909) as the first Labor Premier of Tasmania. He led a minority Labor Government as Premier and Attorney-General from April 1914 until the Government’s defeat at the election of April 1916, when his political attitudes, particularly in relation to the war, were at odds with more radical elements of the Party. Earle was Leader of the Opposition from April 1916 until November 1916, when he resigned from the Labor Party because of his support for conscription, to which the majority of the Party was opposed. According to the Hobart Mercury, he escaped expulsion from the Party only because ‘he got out before the boot could be raised’. Earle’s explanation for his resignation, in an open letter to the Workers’ Political League and the Labor Party, was couched in bitter terms: ‘My reason for this action is because the movement has been corrupted by bodies of extremists, irresponsible and in some cases distinctly disloyal men, aided and abetted by the weakness, cowardice, and treachery of the officers of the organisation and members of the Parliamentary party obtaining control of the movement’.[2]

On 2 March 1917, Earle, now known to be in sympathy with the Federal Government of W. M. Hughes and his pro-conscription Nationalist Party, was chosen to fill the Senate casual vacancy caused by the unexpected and highly controversial resignation of Tasmanian Labor senator, Rudolph Ready. The President of the Senate, Thomas Givens, had announced Ready’s resignation at 6.01 p.m. on Thursday, 1 March 1917. Earle was sworn as a senator the next day, subsequently resigning from the Tasmanian Parliament. Earle’s sudden replacement of Ready was considered by the Hobart Mercury to be a ‘conjuring trick’, devised by Hughes in order to assist his plan of extending the life of the Parliament by the manipulation of selected Labor senators—all Tasmanians. Earle’s arrival in the Senate attracted predictable Labor hostility. Interjections included: ‘traitor to the party’ and ‘over the dead body of a comrade’. Earle denied any intrigue: ‘I have been charged … with plotting to obtain a certain majority. I am absolutely innocent. Everything that has occurred in regard to myself has been absolutely straight and above board’.[3]

In the event, Hughes’ machinations were rendered ineffective when two Tasmanian senators, both Government supporters, Thomas Bakhap and John Keating, disturbed by allegations of bribery levelled against Hughes by New South Wales senator David Watson, announced that they would vote with the Labor Opposition against the Government’s motion for the prolongation of the Parliament. As a result, the Government decided to call an election for the House of Representatives and half the Senate. A motion in March for the appointment of a royal commission to investigate the circumstances surrounding Ready’s resignation and the appointment of Earle to the Senate was defeated on party lines in the House of Representatives. A similar motion had been passed by the Senate.[4]

At the election of May 1917, Earle was returned, under the existing electoral legislation, to fill a casual vacancy to 30 June 1917 and a periodical vacancy for six years. Earle’s principal interests focused on the conduct of the war, repatriation and his continued support for conscription: ‘I am a straight-out conscriptionist, in that I would compel every man, rich or poor, to take his fair share of responsibility to defend the nation. I am against any system which may force one man to go … whilst another man is able to resist and remain’. Earle, who was on the executive of the Tasmanian branch of the Reinforcements Referendum Council, held that voluntary recruiting did not ‘represent the true policy of Democracy, inasmuch as it does not place on every man, who has a right to a share in governing his country, his share of the responsibility of defending it’. His support for the Prime Minister was unequivocal: ‘I say that we have not in Australia to-day another man of the force, character, and power possessed by the present Prime Minister’.

He was full of praise for his home state, which, he told the Senate, was ‘as near Paradise as one is likely to get on earth’. He was in favour of daylight saving on the basis that ‘it would give youth an opportunity to indulge in outdoor games’, would ‘enable the gardener to spend an extra hour in his garden’ and ‘economize in the consumption of gas and electric light’. He expressed a continuing interest in the plight of the blind, supported the continuation of immigration because this would make Australia safer for the white races, and reduce taxation and the national debt. He favoured protection, provided manufacturers undertook to pay a reasonable wage to their employees and to sell their products at a reasonable price. His Labor roots were evident in his claim to be ‘a Socialist’ and in his support for the right of workers to retain their individual rights to strike. However, he held the view that the government had a right to combat any organised refusal to work under an award of the Arbitration Court.[5]

Entitling a somewhat idealistic speech, which followed his appointment in December 1921 to the position of Vice-President of the Executive Council, as ‘Cheer up, Australia’, Earle decried the sober warnings of the press and of opposition senators on industrial relations and the economy. He continued to take an interest in the work of the joint committee of public accounts of which he had been a member until 1920. He served on the select committee on Senate officials, supporting its majority report.

In 1922, Earle failed to secure re-election to the Senate, his term coming to an end on 30 June 1923. He deserted the Nationalists for a time because of the anti-union stand of the Bruce–Page Government, but stood unsuccessfully for the Senate as a Nationalist candidate in 1925. An attempt to gain the Tasmanian House of Assembly seat of Franklin in 1928, as an Independent, also failed.

On 30 April 1914, Earle and Susanna Jane Blackmore had married at St Andrew’s Church of England, Nugent. After Earle’s retirement, the couple lived at Oyster Cove. Earle died at nearby Ketteringon 6 February 1932 and was cremated in Melbourne. Susanna survived him. There were no children. In the Senate, George Pearce said that the Commonwealth had lost ‘a worthy citizen’.[6]

[1] Punch (Melbourne), 22 March 1917, p. 444; F. C. Green (ed.), A Century of Responsible Government: 1856–1956, Government Printer, Hobart, 1956, pp. 217–221; Lloyd Robson, A History of Tasmania: Volume II, Colony and State from 1856 to the 1980s, OUP, Melbourne, 1991, pp. 218–220; Marilyn Lake, ‘John Earle and the Concept of the “Labor Rat”’, Labour History, no. 33, November 1977, pp. 29–38; Ross McMullin, The Light on the Hill: The Australian Labor Party 1891–1991, OUP, Melbourne, 1991, pp. 40, 69; Geoffrey Blainey, The Peaks of Lyell, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1978, pp. 174, 201; Mercury (Hobart), 5 June 1903, p. 2, 6 June 1903, p. 2, 8 June 1903, p. 5; Richard Davis, Eighty Years’ Labor: The ALP in Tasmania, 1903–1983, Sassafras Books and University of Tasmania, Hobart, 1983, pp. 117–119.

[2] Marilyn Lake, A Divided Society: Tasmania During World War I, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1975, pp. 34–37, 70–72, 87, 89; Michael Denholm, ‘Playing the Game: Some Notes on the Second Earle Government, 1914–1916’, THRAPP, vol. 23, December 1976, pp. 149–151; Mercury (Hobart), 5 March 1917, p. 4; McMullin, The Light on the Hill, p. 40; D. J. Murphy (ed.), Labor in Politics: The State Labor Parties in Australia, 1880–1920, UQP, St Lucia, Qld, 1975, pp. 396, 398; Green, A Century of Responsible Government, pp. 220–221; Daily Post (Hobart), 9 January 1917, p. 5.

[3] Mercury (Hobart), 3 March 1917, p. 6; Age (Melbourne), 3 March 1917, pp. 10–11; SMH, 3 March 1917, p. 12; CPD, 1 March 1917, pp. 10779, 10786, 2 March 1917, pp. 10844–10845, 10851.

[4] Age (Melbourne), 6 March 1917, pp. 7–8; CPD, 6 March 1917, pp. 10993–10995; H of R, V&P, 2 March 1917;Senate, Journals, 13 March 1917.

[5] Senate Elections Act 1903–48 (Cwth); Punch (Melbourne), 22 March 1917, p. 444; Robson, A History of Tasmania, p. 331; CPD, 19 July 1917, pp. 280–283, 3 May 1918, pp. 4393–4394, 22 January 1918, p. 3334, 12 March 1920, p. 365, 8 August 1917, pp. 813–814, 5 September 1917, pp. 1649–1650, 1653, 13 October 1920, p. 5531, 12 March 1920, pp. 364–365, 368, 25 September 1918, p. 6315.

[6] CPD, 19 July 1922, pp. 538–547; CPP, Report of the select committee on Senate officials, 1921; Mercury (Hobart), 12 November 1925, pp. 7, 13, 8 February 1932, p. 6; Marilyn Lake, ‘Earle, John’, ADB, vol. 8; Mercury (Hobart), 8 February 1932, p. 6; CPD, 17 February 1932, pp. 13–14, 27–28; Argus (Melbourne), 8 February 1932, p. 7.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 260-263.