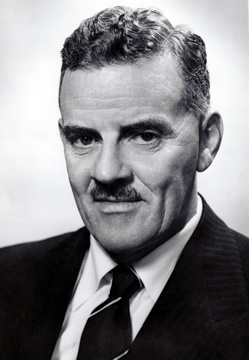

BYRNE, Condon Bryan (1910–1993)

Senator for Queensland, 1951–59, 1968–74 (Australian Labor Party, Queensland Labor Party, Democratic Labor Party)

Condon Bryan Byrne, lawyer, public servant and politician, was born at Yea, a pastoral town in central Victoria, on 25 May 1910. He was the son of Edward James Byrne, a soldier, born at Enniskillen, Ireland, and Mary Honorine, née Condon, born in Tasmania. Condon was educated at a primary school run by the Christian Brothers in West Melbourne, then at Marist Brothers’ College, Bendigo, from 1918. After the family moved to Brisbane, Condon attended St Laurence’s and St Joseph’s colleges, Brisbane. He showed early talent as a public speaker, and was a schoolboy member of a team that won a Queensland Debating Society championship.

In 1928 he joined the Queensland Public Service, rising steadily through the ranks, and also commencing his studies at the University of Queensland, from which he graduated as a BA in 1932. In 1949 he was admitted to the Bar Association of Queensland. In a flourishing career in the public service he became Acting Assistant Under-Secretary of the Department of Labour and Industry. Other appointments included that of private secretary to Vincent Gair when Gair was Secretary for Mines (1942–47), Secretary for Labour and Industry (1947–50) and Treasurer (1950–52). Gair was Byrne’s ally and mentor in the 1940s as Byrne became active in ALP politics. In 1950 Byrne attended the International Labour Office conference in Geneva as a representative of the Queensland Public Service.[1]

He was elected to the Senate for Queensland on the ALP ticket at the federal election of 28 April 1951. He was soon a frequent speaker in the Senate and began to attract notice. However, his chances of making headway within the ALP were to be thwarted by the rising tensions within the party, apparent at the 1956 Labor-in-Politics Convention when Byrne seconded a motion for the establishment of a ‘Labor College’ to provide instruction in the party’s political philosophy. Although the motion was passed, another delegate, with the Industrial Groups in mind, claimed that such an institution might be ‘a breeding ground for some of those forces which have already tried to destroy the Labor Party by other methods’. In April 1957 the Queensland Central Executive (QCE) of the ALP expelled Gair, now Premier of Queensland, from the party, causing the Queensland party to split a few days later, and Gair to form his Queensland Labor Party (QLP). On 23 May Byrne publicly announced his opposition to the action of the QCE, and on 27 August told the Senate that he would now be representing the QLP. Though Byrne may well have been influenced by his religious convictions and ties with Gair, it is more likely that the processes by which party factionalism had brought down the Premier were distasteful to him. Immediately following Byrne’s action, Senator Cole announced that his party, the ALP (Anti-Communist) splinter group formed in 1955, had now changed its name to the Australian Democratic Labor Party (DLP). Byrne, the sole representative of the QLP, now joined Cole and the other DLP senator, Frank McManus, on the cross benches, the QLP opting to remain its own party.[2]

At the federal election of November 1958, in the aftermath of the tortured events of the Labor Split, Byrne, described as QLP federal leader, was defeated (the QLP did not merge with the DLP until 1962). In July 1959 he returned to Brisbane to practise law. He also became president of the Queensland division of the United Nations Association (1959–67).

In 1967 Byrne was re-elected to the Senate for the DLP. By July 1968 the DLP numbered four senators, including Gair, who had been elected to the Senate and appointed party leader in 1964. From 1968 the DLP held the balance of power, the press soon making reference to the Senate’s evolution into a ‘House of information, knowledge and minorities’. In 1968 Byrne became the DLP Whip, and in 1974, the party’s deputy leader. The party lost all its Senate seats in 1974.[3]

Byrne was described by the DLP’s Senator Jack Kane as having ‘had a more gentlemanly attitude to politics than I and was more prepared to give our enemies the benefit of the doubt’. He was less hard-nosed than his mentor, Gair. The journalist, Alan Reid, wrote that Byrne possessed ‘a charitable belief, rare in politics and notably rare in the DLP, particularly as regards ALP opponents, in the good intentions of his opponents’ and that, while he was ‘cultivated, well read and thoughtful’, he was ‘as tough intellectually as the others were politically’. All this made Byrne an effective member of a party credited by some as being the decisive impediment to the election of an ALP government between 1955 and 1972.[4]

Active within the Senate and parliamentary committee systems, a regular and polished speaker on a surprisingly wide range of issues in Senate debate, and capable of negotiating strategic alliances to influence policy, Byrne was a talented politician who may have made a bigger impact if he had pursued his career in a mainstream party. As it was, he gained a good deal of press attention for his party and its causes, especially within Queensland, though after the demise of the DLP he was largely forgotten.

Byrne was certainly a believer in and a spokesman for the causes dear to the DLP: opposition to the communist threat, forward defence and the controversial purchase of the F111 aircraft. Asia was of great interest to him. He visited Manila and Singapore in 1971, as well as South Vietnam as an observer of that nation’s presidential election. In 1969 he had visited India as a member of the Australian delegation to the Inter-Parliamentary Union meetings in New Delhi. He was supportive of the traditional family (and the maintenance of Catholic social action), but he also spoke out on issues such as human rights, pollution, poverty in Australia, conservation and the need to control foreign investment and foreign ownership within Australia.[5]

Byrne regarded the establishment of the standing committee system in 1970 as ‘a tremendous pioneering project in the operation of the Senate and parliamentary government in this country’, and was the leading DLP spokesman on the subject. He said that he had done his best ‘not to intrude party political considerations’ into the debate, a claim that was essentially true. In common with his party colleagues he preferred to see specialised standing and estimates committees introduced gradually, but he did not vote against the successful motion of Senator Murphy to refer the question of assistance to mentally and physically handicapped people to the Standing Committee on Health and Welfare in September 1970, the first such reference to one of the new committees. He proposed specific rather than broad references to committees, and adamantly defended the rights of ‘the minority groups’ to committee representation. In keeping with his high regard for the Senate’s review processes and the procedures of parliamentary democracy, Byrne’s committee service was notable, including as deputy chairman of the Joint Committee of Public Accounts from 1952 to 1955, and later as a member of the Constitutional and Legal Affairs Committee, and the influential Select Committee on Foreign Ownership and Control of Australian Resources. He also served as a temporary chairman of committees from 1969.[6]

Byrne was not one for making political enemies. He was, according to Kane, ‘amiable [and] well-liked’, and was able to build consensus positions between the parties, as he endeavoured to promote reconciliation of interests and maintain friendships with former colleagues in the ALP. He was remembered, even by such a stalwart of the Labor left as Tom Uren (former MHR), as someone to respect and ‘a good human character’.

With all members of his party, Byrne was defeated at the 1974 federal election and returned to his law practice in Brisbane. He remained a patron of the Queensland Debating Union, and followed various recreational and sporting activities, in particular, horse racing. He never married, and shared a house in Brisbane with his sister, who predeceased him. Byrne died on 25 November 1993. His obituary in the Australian was written by the former MHR for Moreton and Liberal minister, Sir James Killen, who described his friend as ‘a man of conscience’. Senator Harradine recalled Byrne’s ‘firm attachment to his Catholic faith’ and how on several occasions in the Senate, Byrne would, inadvertently, pull out of his trouser pocket a number of items—‘some loose coins, a packet of cigars and a set of rosary beads which would clatter on to his desk’. Harradine saw Condon Byrne as belonging to a Labor tradition that ‘in earlier times’ had found ‘coexistence with a philosophy of social action based on religious beliefs’.[7]

[1] The editor is indebted to Leonie Hannah, Librarian, Catholic College, Bendigo, Cecily Hesse, College Registrar, St Joseph’s College, Gregory Terrace, Brisbane, Bruce Ibsen, UQ Archives, and Sandy Zillman, Bar Association of Queensland; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 26 Nov. 1993, p. 18; Byrne, Condon Bryan, Personnel file 8452, item ID934979, QSA.

[2] Don Whitington, Ring the Bells: A Dictionary of Australian Federal Politics, Georgian House, Melbourne, 1956, p. 23; ALP, Official record of the 22nd Queensland Labor-in-Politics Convention, 1956, p. 43; Frank Mines, Gair, Arrow Press, Canberra, 1975, pp. 85–9; SMH, 24 May 1957, p. 4, 30 May 1957, p. 2; CPD, 27 Aug. 1957, pp. 10, 12; Joan Rydon, A Federal Legislature: The Australian Commonwealth Parliament 1901–1980, OUP, Melbourne, 1986, p. 33.

[3] Robert Murray, The Split: Australian Labor in the Fifties, Cheshire, Melbourne, 1970, p. 348; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 6 July 1959. p. 5; Age (Melb.), 13 Aug. 1968, p. 8; AFR (Syd.), 20 Nov. 1970, p. 2.

[4] Jack Kane, Exploding the Myths: The Political Memoirs of Jack Kane, A & R, North Ryde, NSW, 1989, p. 219; Alan Reid, The Gorton Experiment, Shakespeare Head Press, Sydney, 1971, p. 145.

[5] Sun News-Pictorial (Melb.), 7 Nov. 1970, p. 13; Reid, The Gorton Experiment, p. 161; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 12 Oct. 1971, p. 10, 29 Oct. 1969, p. 1; Australian (Syd.), 11 July 1968, p. 4; CPD, 17 Sept. 1970, pp. 704–8; Australian (Syd.), 1 Feb. 1969, p. 4; CPD, 13 May 1970, pp. 1390–2; Courier-Mail (Brisb.), 6 Nov. 1971, p. 1.

[6] CPD, 19 Aug. 1970, p. 104, 25 Aug. 1970, p. 198, 11 June 1970, pp. 2360–2, 2 Sept. 1970, pp. 409–10, 413.

[7] Kane, Exploding the Myths, p. 219; Tom Uren, Straight Left, Random House, Milsons Point, NSW, 1994, p. 232; Australian (Syd.), 15 Dec. 1993, p. 13; CPD, 7 Dec. 1993, pp. 4014–15.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 3, 1962-1983, University of New South Wales Press Ltd, Sydney, 2010, pp. 305-308.